Sanchari Bhattacharya in Mumbai

Four years, one trial, an irreparable tragedy and several tribulations later, Bedabrata Pain is ready with his first film Chittagong, releasing this Friday.

As a PhD student of applied physics at Columbia University in the early 1990s, Bedabrata Pain had perfected the "three backpacks, three sweaters" trick to stay out of trouble.

"I switched them around so that my advisor would think I was there everyday, working, when I would actually be somewhere else," confesses the scientist-turned-filmmaker.

Pain shares this anecdote to emphasise that he was never quite the proverbial science geek, in spite of what his stellar career may suggest.

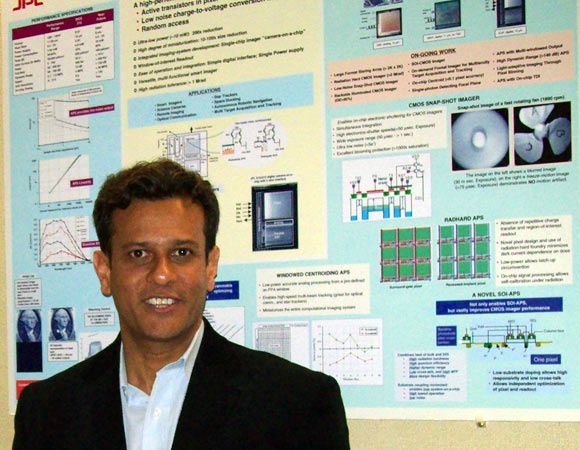

Sure, he was part of a team that invented the CMOS image sensor, which pretty much changed the world of digital imagery and has since spawned a 10 billion dollar industry.

Yes, he has been inducted into the United States Space Technology Hall of Fame and has 87 patents to his credit. And he has worked as a senior scientist with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at National Aeronautics and Space Administration for 18 years.

But, says Pain, he was never really a "nerdy, techy guy".

'The first time I heard about a cell phone camera, I thought 'what a stupid idea''

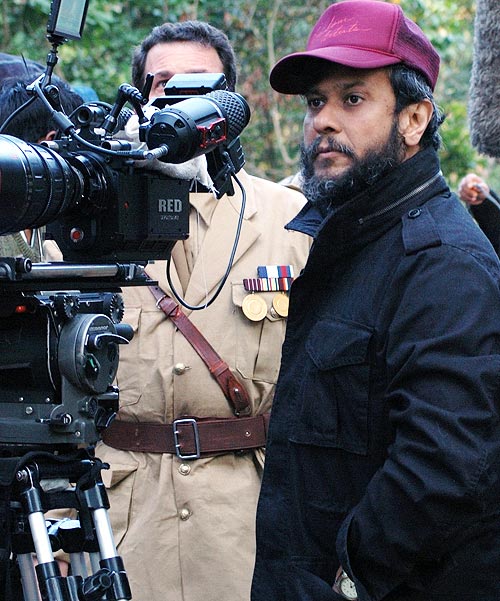

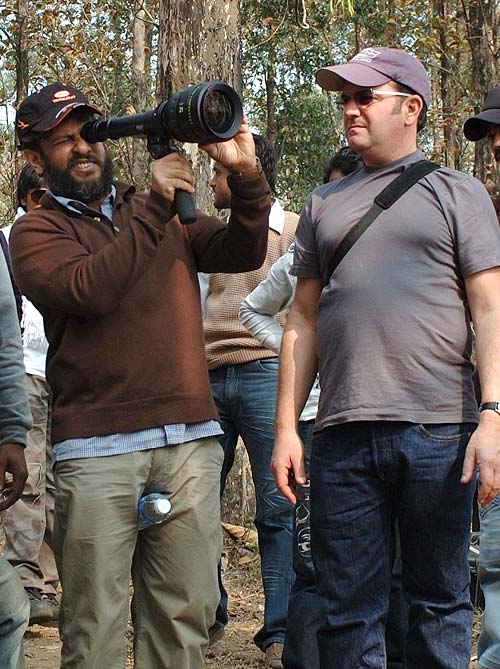

Image: Bedabrata Pain, on the sets of ChittagongAt Columbia University, Pain used his time away from the laboratory well, dabbling in a multitude of cultural activities.

He wrote plays, composed songs, organised cultural events, participated in protests against the Gulf War and demonstrations against human rights violations, and even wrote a booklet on the Kashmir conflict.

So the decision to apply brakes to the 'American Dream' in 2008 and take up a not-so-dreamy vocation was maybe an unusual one, but not entirely unexpected in his case.

Four years, one trial, an irreparable tragedy and several tribulations later, Pain is ready with his first film. Chittagong, starring Manoj Bajpayee and Nawazuddin Siddiqui, releases in India on October 12.

Incidentally, this is not the first time Pain has faced doubts and misgivings about his chosen path. When he was one of the four scientists working on a 'smart chip' during his post-doctorate at the JPL, he was used to not too many people in the scientific community taking his team's efforts seriously.

They were told that the chip would never work, that it would be merely a 'toy'.

The 'toy' soon went on to revolutionise the world of digital imagery. Today, it is used in nearly 95 per cent of digital equipment -- in everything from an optical mouse to cell phone cameras.

"The first time I heard about a cell phone camera, I thought 'what a stupid idea'. Why would anybody want to take pictures with their cell phones," recalls an amused Pain.

'Being a good Bengali, I could not become an entrepreneur'

Image: Bedabrata Pain, on the sets of Chittagong"He called me up one day and said 'you are not doing anything'. My survival instinct kicked in. I thought I had to do something or I will be thrown out of the programme," says Pain.

So, Pain and three of his colleagues set to work. They created a "smart chip that collects images effectively and represents it digitally.

"It was a simple idea. Simplicity is the hallmark of a genius," quips Pain, adding quickly, "not that I am a genius".

For the next one-and-a-half decade, he continued working at NASA, letting go of lucrative opportunities to cash in on his invention. "Being a good Bengali, I could not become an entrepreneur," he deadpans.

'Leaving my high-powered job wasn't an easy decision to make'

Image: On the sets of ChittagongHe had been toying with the idea for nearly two years before he finally took the plunge.

"It was not an easy decision to make. My parents needed a house, my children needed their education. I don't know if it was the right thing to do, but I did it anyway," he says, a tad wistfully.

Eric Fossum, co-inventor of the CMOS image sensor, had once told Pain that by the age of 45, one should be 'settled'.

"Well, at 45, I threw my life wide open and started on one of the most arduous journeys of my life," declares Pain.

For the passionate desire to make a film, a relentless (and untranslatable) keeda had gotten hold of him by then, and it was refusing to let go.

By that time, Pain had already worked as the producer and principal researcher for a documentary called Lifting the Veil. He was also one of the producers of Amu, a critically acclaimed film directed by his wife Shonali Bose.

'I was jumping into the unknown, and Shonali was fully behind the decision'

Image: Bedabrata PainBut making a film, Pain soon learnt the hard way, required "infinite patience and infinite humility".

"I was at the top of my game at NASA. And then, with films, I was at the bottom of the barrel. I was used to picking up the phone and getting things done. Here, many people would not even respond to my calls. It was a humbling experience," Pain says of his teething troubles.

People not taking his calls would turn out to be the least of his problems while making Chittagong. Murphy would have been thrilled, observes Pain wryly, for everything that could go wrong while making the film, eventually did.

To begin with, the financiers who had promised to fund the film backed out after the recession started pinching their pockets. Pain tried to raise funds in the US but struck out again.

'It was all about planning for everything and preparing for the worst'

Image: Bedabrata Pain, on the sets of ChittagongThis, he quips, has made him so broke that he may soon have to "look for freeway underpasses to live in".

After Pain managed to make the film on a shoe-string budget with his own money, he was advised against releasing it because an A-list Bollywood filmmaker had, in a curious coincidence, made a film on the very same subject.

The fact that this much-hyped film tanked royally did not make things any easier for Pain. And he had to wait for months to find the right people to distribute his film as, Pain observes, "making a film and releasing it are two completely different things".

For Pain, the first day of shooting -- at Latagudi in North Bengal -- was also the first time he had ever set foot inside a film set. The challenges were numerous and the time to overcome them was ticking away. His 200-odd crew was not very sure of how he would manage the show and he had to work hard to earn their respect. Pain had to learn the on-set lingo about technical equipment.

He had to be open to ideas put forward by other people while remaining true to his own vision.

Pain sums up his first foray into direction, "It was all about planning for everything and preparing for the worst".

The shoot, wrapped up in an impressive 42 days due to budgetary constraints, was gruelling. Pain and his crew members spent up to 16 hours a day on the set. The director would then have to interact at length with the actors and plan out next day's shooting schedule.

And then, with the creaky internet connection available in rural Bengal, Pain would help his 16-year-old son Ishan, who was studying in Los Angeles, crack the mysteries of advanced chemistry on Skype.

"He could make out how tired I was. He would say 'don't worry Baba, I will figure it out'," recalls Pain warmly.

He finished shooting most of the film by May 2010 and planned to release it soon after. But a devastating personal tragedy completely blindsided him and relegated everything else to the background.

Ishan was killed in a freak electrical accident on September 13, 2010.

In a shocking verdict, a court in Los Angeles recently refused to hold the electrical razor company responsible for Ishan's death.

'I went from having it all to losing almost everything'

Image: Bedabrata Pain"It was an open and shut case, but the defence had put up too many red herrings. I have had two years to confront the evidence. Now I am convinced more than ever, scientifically and logically, that there was a fault with the electrical shaver. Earlier, it had been more of an emotional response," he says.

During the trial, defence lawyers had crassly asked him and his wife about how much they had spent on their son's school fees. They were asked how much Ishan would have been able to provide to them monetarily, had he lived.

"They were asking the jury to determine the value of a human life. How do you put a value on someone's life? I realised that this system can't evaluate a human life beyond its money making capacity," laments Pain.

"Which parent would want to cremate their child," he adds, his voice faltering.

Ishan and his father were extremely close and they used to discuss everything -- from history and science to politics. One of their favourite topics was Nobel Laureates and the scientific achievement that had fetched them the honour.

"I used to take him to school everyday. I had helped him write his last school essay. It doesn't feel like he is gone. Sometimes I think he has just gone off to school and he will soon turn up," says Pain.

The days following Ishan's death were the worst of his life. As Pain puts it bluntly, "I went from having it all to losing almost everything."

But the memory of Ishan -- who has supported him whole-heartedly while he was making Chittagong -- kept him afloat. It was the hardest thing he had ever done, but Pain continued to work on the film, even reworking parts of it.

While Chittagong releases across India on October 12, Pain held a special memorial screening of the film in Mumbai last week, attended by Shah Rukh Khan and Amitabh and Jaya Bachchan, among others.

Though he claims that "people who have seen it, loved the film", Pain is not too bothered about negative feedback from the audience or the critics.

"Ishan and I shared a belief that when you want to do something, give it your 200 per cent. Make it the best it can be. There is no guarantee that others will also think it is the best. But you separate yourself from the result. Let's see what happens," he says.

Comment

article