Abhishek Mande in Mumbai

Nationalism only comes second to a writer whose primary morality is as a human being, Mohsin Hamid tells Abhishek Mande, as Mira Nair's The Reluctant Fundamentalist, based on his book, hits the theaters on May 17.

Mohsin Hamid doesn't see himself as a Diasporic author and indeed his concerns are far different from those of his illustrious predecessors.

While the Rushdies, Ghoshs and Lahiris spoke wistfully among other things about the rootlessness of their existence, Hamid belongs to the generation that, in some ways, celebrates this very phenomenon.

While Lahore remains his home, Hamid has over the years, struck roots in cities like New York and London and has found home in each of these cities.

Hamid graduated from Princeton in 1993, studied under Toni Morrison and Joyce Carol Oates before going on to study law at the Harvard Law School.

In between serving as a management consultant at McKinsey & Company in New York City, he managed to complete the first draft of what would become his first novel, Moth Smoke.

By the beginning of the noughties, Hamid had moved to London hoping to stay there for just a year. The year stretched to eight and before he knew it he had found yet another home in the world.

In his conversation with Abhishek Mande, he discusses the process of seeing his book The Reluctant Fundamentalist being made into a movie by Mira Nair, the post 9/11 generation of novelists and the concerns of his homeland.

When a book is translated, something is lost. So what would you say was lost with The Reluctant Fundamentalist?

I think the book is a technology that requires the reader to decode and recreate a story. And the way the reader does it, is unique to that reader. A film, on the other hand (offers that take for you).

In that sense, in any adaptation, the experience of you, the reader as the cinematographer of your personal experience of a novel, is lost.

Just the way it changes, characters change... and all sorts of things change and that, of course, has happened in the adaptation of The Reluctant Fundamentalist as well.

But I do not think of it in terms of loss as such, but I do think of it as (being) different.

This was supposed to be the corollary to my question: Salman Rushdie has suggested that while it is generally believed that something always gets lost in translation, something can also be gained.

While Rushdie was speaking about translating from one language into another, I've always been curious to understand what is it that is gained when a piece of work moves from one medium into another.

'I was much more involved than I intended to be'

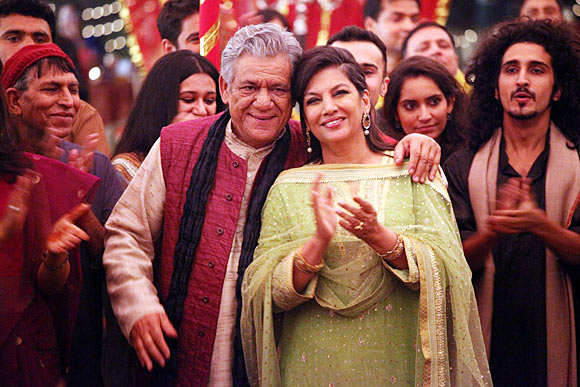

Image: Om Puri and Shabana Azmi in The Reluctant Fundamentalist

What do you think has been gained in the adaptation of The Reluctant Fundamentalist?

Well, many things are gained; there are entirely different visual sights, sounds, there's music -- all sorts of things that don't belong in the medium of text, but belong to the medium of film.

But what we are talking about here is really transmutation. We are talking about picking one thing and moving it into another thing.

If you make a sculpture inspired by a song, have you translated that song? I don't think so. So, translation becomes a very slippery word when you use it that way.

I think what we are really talking about is an entirely new piece of work, a new work that is inspired by some other work.

What apprehensions did you have when you realised that your book was being made into a movie?

All sorts of apprehensions, I must confess!

Will the movie be something which I love... There's the natural apprehension of what this is going to be.

Then there is a separate apprehension that is probably peculiar to writers of novels being adapted into films, which is the idea that in some way, someone is taking your creation and doing something with it.

Because the movie is inspired by your novel, you start to think that the film is, in some way, also your novel and then you start to get very nervous! It's a bit like giving your child over to a new teacher at the start of the school day and you hope that at the end of the day, the child you get back is happy and not beaten up and has learnt something! (Laughs)

Then, of course, the idea is that as a novelist, I create exactly what I want to create, but film is an entirely collaborative effort. It's like taking an introvert and throwing him into a wild and crazy party.

So, as a 'parent' where did you draw the line and say 'I'm not going to get any more involved in the process of filmmaking'?

I was much more involved than I intended to be.

My initial plan was that I was going to hand over everything to the filmmaker that I trust and respect and I was going to sit back and watch the movie after it was done. And I thought that would be the easiest way emotionally.

But as the film happened, it was very difficult to find a screenwriter who understood both the corporate New York and (the everyday) Lahore. So, I got involved in the early part of screenwriting.

There were also a number of decisions along the way about characters, their appearances, about whether the setting looked like Lahore or if particular words were used in Lahore, etc. So, despite my intention to just come to the premiere of the film, I (ended up) participating in lots of ways, sometimes smaller, sometimes larger -- right from being involved in the screenplay to giving it newness.

'Many Pakistanis find it very difficult to travel abroad'

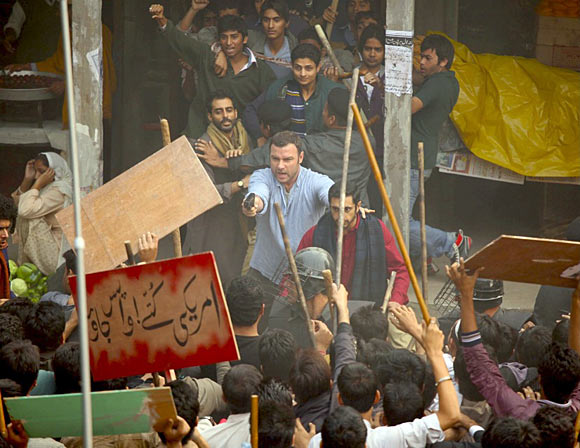

Image: Meesha Shafi in The Reluctant Fundamentalist

On a personal note, may I ask you if Liev Schreiber was your choice?

Nobody was my choice, in the sense that I didn't pick the actors in the film.

I'm quite thrilled with the actors in the film. Whether its Riz Ahmed as the protagonist and Shabana Azmi and Om Puri as his parents or Meesha Shafi as her sister or Liev Schreiber or Kate Hudson as his girlfriend or Kiefer Sutherland as his boss... these are people I am thrilled are involved in the film.

In an interview about the movie, you had said that in Pakistan, there's a sense of 'intense isolation.' What kind of isolation were you talking about -- individual or political?

I don't remember the exact context of this, but isolation takes many different forms. While issuing visas, for instance. Many Pakistanis find it very difficult to travel abroad.

Foreigners are deterred from coming to Pakistan by a combination of deception and to a certain degree, a sense of risk. So, people can't travel from and to our country so there are few cultural opportunities to interact. That's the kind of sense of isolation and I do feel in Pakistan that sense of being somewhat cut off.

Would you say this political isolation leading to isolation of self?

Well, I don't know. People such as us -- who write books or make films -- talk about being isolated within the self. That's a difficult question to generalise.

It is hard for me to say whether Pakistanis feel they are isolated within themselves and an announcement will imply I have a great deal of world knowledge of the Pakistani psyche, if there is such a thing.

Personally, I feel less against the sense of isolation because I am a fortunate Pakistani who does get to travel quite a bit. I, however, do feel concealment and frustration for sure.

Sometime after Pakistani lawmaker Salman Taseer's assassination, author Kamila Shamsie said the sense of antagonism towards Pakistan has in some way given way to pity, where people say, 'Oh so you are from Pakistan. I am so sorry about that.' Is that something you have come across too?

My experience is not much of that. But a sense of compassion I think is a more positive feeling, which (involves) understanding the difficulty of what someone is going through without feeling a sense of superiority over that person.

That is something I have felt from many people outside of Pakistan.

'My job is to describe the world that I see and to speak in the way that I think is honest'

Image: Liev Schreiber in The Reluctant Fundamentalist

As a Pakistani, do you find yourself defending your country more than let's say an Indian would?

I don't really think of it that way, to be honest with you. It's not my job to defend my country. My job is to describe the world that I see and to speak in the way that I think is honest. I am not trying to craft a series of policy pronouncements or propaganda messages that result in greater national security, that's not what I aspire to do.

I don't think it's the job of a novelist to be the defender of the nation. In fact when you start doing that, you are making your nation less safe.

For me, it's much more useful to talk to people, if they have conceptions about Pakistan that differ from my view of Pakistan and explore what those differences are and tell stories instead of bullet points or article headlines.

Even as a citizen, I think there's a kind of nationalistic outlook embodied in the idea that I am a defender of Pakistan. I think I am someone who lives in Pakistan, has enormous affection for it and also sees with clear eyes the problems of the country. But I hope that the things that I have tried to defend are of value to people who are not just in Pakistan but in other places also.

My first morality is as a human being and to other human beings as human beings and only very secondarily comes the morality that is nationalism.

Also, when we try to defend our country we tend to blind ourselves to the problems that are there in the country just like we do (within our) families.

The second (mistake we commit) is that we attack something else because that is often the most effective way to defend something. Neither of these strikes me as being particularly useful.

How is Pakistan negotiating its fundamental and liberal extremes?

Polarization in Pakistan is happening at two levels economic and cultural. The key for Pakistan is to find a way where very different people with very different points of views can co-exist. That is the real challenge in Pakistan.

If this challenge is not managed well, the result is conflict and bloodshed and lost opportunity.

Most of us outside Pakistan are only exposed to what is written in English. What is the mood in the Urdu-speaking media?

I think that regionalist tone does creep up in the Urdu language media because Urdu has so much more reach and, therefore, more significance on television.

You do have a more nationalistic, chauvinistic or ideological perspective, high-pitched tone on the Urdu language talk shows considerably.

What we see on Fox News in America, you see it in Urdu mass media in Pakistan and that is in the absence of clean and effective solutions. There are too big polarizations and inequalities going on in our society. We tend to nationalism and, as you say, defend the nation as a pseudo solution. It's an attempt to distract attention from the real issues

Despite that though, you also have some real voices of sanity in the form of some very big people and some very interesting artists (who counter that).

'The '80s and its aftermath have shaken Pakistan today'

Image: Kate Hudson and Riz Ahmed in The Reluctant Fundamentalist

Someone once told me that what we are seeing in Pakistan today is a consequence of the Jihadi mentality since the Zia-ul-Haq years. The point of reference was the age of the guard (in his 30s) who killed Taseer and was hailed...

Well there is no doubt that in 1980s Pakistan was changed, emphasis on Jihad was brought into text books and mentor groups originally gave birth to movements against US involvement in Pakistan.

Certainly the '80s and its aftermath have shaken Pakistan today. But it's also important to keep in mind that most Pakistanis are 22 or younger, which means, in a way that is a very hopeful nation.

There are an enormous lot of young people who will have to turn the future of the country of theirs and are open to change, and I hope new ideas, new thoughts will capture their imagination.

You say that the man who killed Taseer was in his 30s, which makes him seem young but actually in the Pakistani sense, he hopefully belongs more to the past than to the future. But we don't yet know...

In a 2006 interview, you've been quite critical about India blaming Pakistan for every other terrorist attack. It would be interesting to understand from you what would be the three things that India and Pakistan should look into before we move ahead.

I think between both India and Pakistan, if you travel between two places, it is very difficult to find two countries so similar yet so isolated from each other.

Perhaps North Korea and South Korea maybe (but that's it).

So, the first thing would be to acknowledge the similarities instead of dwelling upon the problems.

The second thing is, once and for all, to accept the dictates of geography, engage one another much more robustly instead of waiting for problems to simply go away...

Finally, (it is crucial) to recognise the enormous hope and that each represents for the other.

A positive relationship with Pakistan will not just kindle economic hope (and pave) way for India to integrate with many countries to its West, but also change the religious dynamics of India's relationship with the poor Muslim minority and change the problem of religious conflict.

I mean there is so much opportunity that Pakistan presents to India and it's the same for Pakistan.

There is so much that Pakistan can learn from India, that Pakistan can benefit from India.

However, to begin seeing each other as a source of hope and improvement seems like a huge task.

Finally, since you are now in Lahore, do you see this as the city you would settle down in for good?

I don't know, I 'settled down for good' in Lahore before, so I am not yet sure. I am fully steady in my career as a novelist now, so I am not likely to shuffle with other professions.

Comment

article