| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Hindi cinema has gained a certain cultural legitimacy'

Unlike many intellectuals who take a disparaging view of Bollywood films, Tejaswini Ganti has written a book that is a fond, but also critical, assessment of how films are made and marketed in Mumbai.

Producing Bollywood: Inside the Contemporary Hindi Film Industry (Duke 2012), examines the social and institutional transformations of the Hindi film industry from 1994 to 2010.

Ganti has watched hundreds of Bollywood films and also worked as an assistant director on a Yash Raj film, Dil To Pagal Hai, directed by veteran Yash Chopra.

Ganti, associate professor in the anthropology department and its programme in culture and media at New York University, is a visual anthropologist specialising in South Asia.

She has been conducting ethnographic research about the social world and filmmaking practices of the Hindi film industry since 1996 and has also written Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema (Routledge 2004).

She produced the documentary, Gimme Somethin' to Dance to! (1995) which explored the significance of bhangra music for South Asians in the United States.

Ganti is an alumna of the University of Pennsylvania and New York University.

'This is the first book on Bollywood,' wrote Arjun Appadurai, professor at NYU, 'to combine a deep knowledge of the dynamics of script, song, stars, and style in this cinematic world with an equally keen sense of the unique nature of the politics, finance, and cultural prejudices of the film industry.'

In this interview with Arthur J Pais, she talks about her book and the changing face of Hindi cinema.

How did this project start and how did you go around researching it?

I have grown up with Hindi cinema. It had always been my primary mode of entertainment from the time I was a young child. Although I thoroughly enjoyed Hindi cinema, I never thought it would become a part of my professional life.

I had advisers in graduate school who became aware of my longstanding interest and personal passion for Hindi cinema and encouraged me to pursue research about it. In the early 1990s, cultural anthropology was undergoing a great deal of transformation and becoming open to the study of topics such as mass media and popular culture.

In anthropology our main research method is what we call 'participant observation', which means that we derive our information about a particular community, society, or group, from immersing ourselves in that particular social world and observing and interacting with people within it.

To carry out this project, I lived in Bombay (Mumbai) for a year in 1996 and then I did subsequent fieldwork in 2000, 2005, 2006. I have also observed Hindi film shoots in the US over the last decade. I spent the bulk of my time on film sets, (in) filmmakers' offices, editing studios, dubbing studios, outdoor shoots, and other sites of production; I also worked as an assistant on two films.

I carried out formal, taped interviews with about a hundred people in the industry over many years, but the daily conversations and interactions that I had with industry members play a central role in my analysis of the Hindi film industry.

'I was struck by how approachable stars like Aamir and SRK were'

What are some of the most surprising things you came across?

First, I was quite surprised at how open people were to my research project.

Of course, I went to Bombay armed with a few key contacts -- people who had I met in Philadelphia and New York who had close connections to the film world -- but I was quite struck by how approachable most people in the industry were, from stars like Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan to directors like Raakesh Roshan and Subhash Ghai.

In fact, when I first started my research I was quite taken aback by the immediacy with which people were willing to grant an interview, especially on film sets! I learned very quickly that I always needed to carry my tape-recorder and lists of questions with me because I never knew when a chance meeting could result in an interview.

I also learned how the set was really a very public space where much of the industry's business gets conducted, from interviews with journalists to deals with distributors.

Second, I was quite struck by how members of the industry themselves were so critical of their work culture, production practices and quality of filmmaking.

Throughout my fieldwork, I encountered filmmakers criticising every aspect of the industry -- from the working style to the sorts of films being made. It seemed as if filmmakers had internalized all of the criticisms leveled against them by journalists, government officials, intellectuals, and anyone else who frequently commented upon filmmaking in India.

However, the more I thought about it and paid attention to their criticisms, I realised that these criticisms served a crucial function, which I discuss in the book, of trying to erect symbolic boundaries in a context where anyone with large sums of money has been able to make a film.

Unlike many other industries, the Hindi film industry for much of its history has been characterized by porous boundaries and very few barriers to entry, and that has been a source of anxiety and criticism for the government and filmmakers alike.

'Raj Kapoor, Amitabh Bachchan were very popular among the non-South Asian audiences'

You told the Christian Science Monitor that Bollywood has always been global. Please elaborate.

I won't use the term Bollywood to refer to all of the periods of Hindi cinema. If you look at the history of Hindi cinema, it has been marked by a tremendous amount of cultural diversity. Not only were members of the Hindi film industry from every region in South Asia, but they were from Europe and Australia as well.

For example, Bombay Talkies, which was one of the prominent studios of the 1930s, had Germans working in key positions as directors and cinematographers. One of the top stars of the 1930s was Fearless Nadia, the screen name of Mary Evans who was originally from Australia.

Ardeshir Irani who made the first sound film in Hindi also made the first Farsi language film for the Iranian market, so an important strand of Iranian film history can be traced back to Bombay.

When we move from production to circulation, we find that Hindi films have circulated all across the world since the 1950s -- Morocco, Egypt, Nigeria, Ghana, Israel, Tanzania, Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Poland, Indonesia, Soviet Union, Peru, China, and many more countries without any significant (Indian) Diasporic community -- without any marketing effort on the part of their producers.

These films circulated far and wide and cultivated loyal audiences and the producers sitting in Bombay had no idea. Raj Kapoor, Amitabh Bachchan, and Mithun Chakraborty were all very popular among vast numbers of non-South Asian audiences.

You also said, 'The Indian government has also finally woken up to this and sees it as something to be promoted now.... (Bollywood) has become part of the Indian package of a contemporary, emerging global power, which is very different from 15 years ago.'

I think what is quite remarkable is how despite years of hostile or indifferent government policies, high rates of taxation, complete disinterest by much of the organised sector, scarcity of capital, and a very decentralised structure, the Hindi film industry managed to survive and continue to make films that were successful, touched people's hearts, and were seen by millions of people all over the world.

'Madhuri Dixit told me that she had never encountered a female assistant'

What are the welcome changes in the production of Bollywood films apart from better high tech?

First, the fact that there are more women involved in the production process. When I first began my research, apart from a few choreographers, costume designers, hairdressers and Sharmishta Roy, the art director, there were no women working behind the camera.

In fact, if the heroine or dancers were not present for a shoot, I was often the only woman on a film set. When I worked briefly as an assistant on Dil To Pagal Hai in 1996, I was such an anomaly that Madhuri Dixit struck up a conversation with me. She told me that she had never encountered a female assistant in all her years of shooting.

Second, the business side of the industry is willing to support filmmaking that does not always appear conventional -- in terms of genre, theme, or use of music.

The changes in distribution and exhibition structures have enabled a greater variety of films to reach audiences.

'It was incredible to see so many people waiting to see DDLJ in Manhattan!'

Bollywood used to depend on open market financing, borrowing at very high rates from financiers and at times from the underworld. Has the financing become more responsible and streamlined?

Definitely, with the entry of companies like UTV, Reliance Big, Sahara, Percept, Shree Ashtavinayak that are collectively referred to as the 'corporates', as well as established banners like Mukta Arts becoming publicly traded companies on the Bombay Stock Exchange, raising finance for the established filmmakers is no longer the piecemeal process it used to be.

Producers usually just sell the all-India and/or global distribution rights to a company like UTV or Reliance and get their working capital at one go.

With a steady and reliable source of finance, films are also being completed in a shorter amount of time.

What has been your movie-going experience over the years?

I have always managed to watch Hindi films in a movie theater, no matter where I have lived in the US, whether it is suburban Houston, suburban Philadelphia, or suburban Connecticut. I keep a diary of where I watch Hindi films, which has become a great record of the remarkable itineraries followed by Hindi films in this country.

My most memorable Hindi film experiences are the ones where the show is sold out and hundreds of people are partaking in a collective experience of entertainment.

I remember going to see Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge in New York in 1995 at the Gramercy Twin on 23rd Street and the line for the film snaked around the block.

It was incredible to see so many people waiting in line to see a Hindi film in Manhattan! It suddenly appeared as if a little part of India was transplanted in the middle of New York City, and I remember the traffic slowing down and people trying to figure out what was happening.

A more recent experience that was great fun was watching Rockstar in the AMC Empire 25 at Times Square in New York on a Saturday night; during the Sadda Haq song, all of the Tibetans in the audience gave out a loud cheer and clapped jubilantly when they saw the sequences in the song shot with the Tibetan community in India.

'There are no more poor or working class people in some of the recent films'

There was a time academics dismissed popular cinema. A few people are now looking at Bollywood without being judgmental. What kind of progressive elements have you found in some of the more popular films?

Actually, my whole book is about how Hindi cinema has gained a certain cultural legitimacy that was unanticipated when I first began my research in 1996.

If you think about Hindi cinema's obsession with romantic love, that is quite socially radical, especially since Hindi films have for most of their history promoted love across social barriers of class, caste, or religion.

Hindi films have also been concerned with questions of social justice for a really long time -- whether they were films starring Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar, or Amitabh Bachchan.

Ironically, the time when films start to be less looked down upon by academics, intellectuals, and journalists is the same time they start losing their progressive elements.

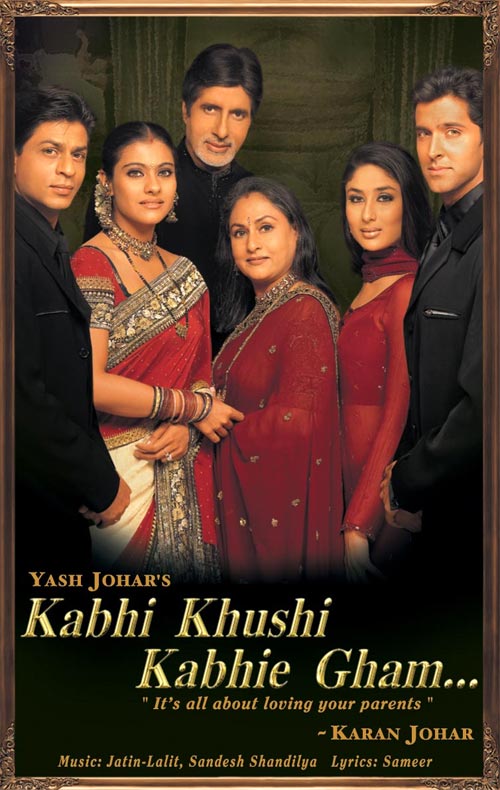

All of the really popular films from the 1990s to 2001 like Hum Aapke Hain Koun, Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, Dil to Pagal Hai, Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham and others are much more conservative than what came earlier. Neither is there rebellion, nor is there concern with social justice.

In fact, there are also no more poor or working class people in these films.

I discuss this in my book, about how Hindi films in the late 1990s became 'gentrified,' and thereby became more culturally legitimate from the point of view of the state, English-language media, and middle-class audiences in India.