| « Back to article | Print this article |

Immortals: Moving away from staid classical story-telling

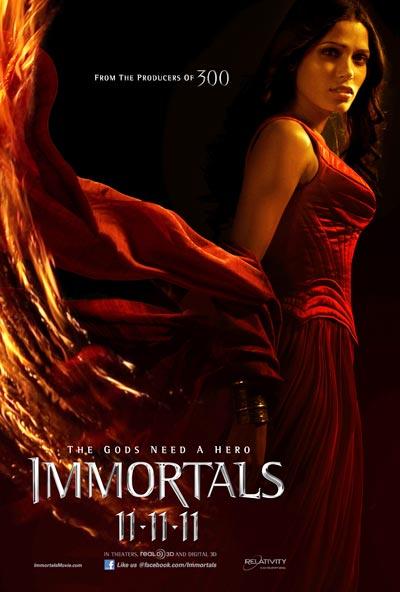

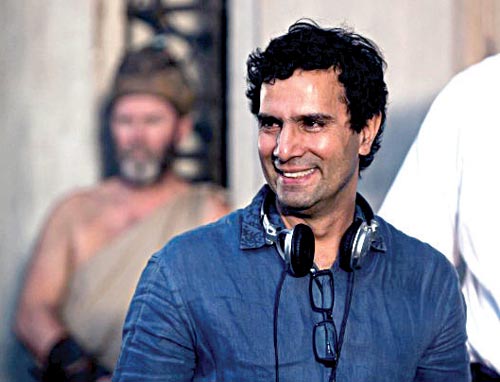

Upcoming blockbuster action adventure film Immortals unfurls a heroic battle between gods and mortals. It also showcases the talent of two desis -- visionary director Tarsem Singh and actor Freida Pinto. Arthur J Pais reports:

Eleven years ago, Tarsem Dhandwar Singh took his mother Harbans Kaur to see his first feature film The Cell. When it first released many complained it was too violent. His mom enjoyed it and the graphic violence did not bother her.

The film went on to be a medium-range hit in the theaters and Tarsem, as he prefers to be called, became known as a director of haunting images and compelling story telling. The man who had made a number of hit video films especially REM's Losing My Religion (which fetched a number of awards including a Grammy) and commercials for multinational giants such as Pepsi, was suddenly an A-list director and The Cell has become one of the big cult hits on DVD. It was the narration of an intensely psychological tale that had hooked his mother.

Heads explode and limbs fly across the screen in his third film Immortals, which follows the more benign adventure fantasy The Fall, which was released five years ago but despite some good reviews did not find a distributor. The Fall was a visual fantasy seen through the eyes of a young girl and a bedridden stuntman who conjures stories about five exotic brigands roaming the world looking for treasure; the film was a setback to Tarsem in his Hollywood journey.

Finding a new footing with Immortals

But the about-to-be-released Immortals is already putting his career on a new track. He is already working on a new version of Snow White featuring Oscar winner Julia Roberts for Relativity Media, the producers of Immortals. The $75 million Immortals -- an average budget for a Hollywood film -- is in 3D and comes from the same producers who scored a surprise hit with their historical yarn 300 a few years ago, earning $460 million worldwide.

Tarsem's mom has not yet seen Immortals, which was inspired by Greek mythology, the 50-year-old filmmaker says from his Beverley Hill office, as she is in London visiting his sister. But he certainly expects her to fall for the film's intriguing story of a faithless man slowly becoming heroic and fighting evil as he makes some interesting discoveries about the gods.

Immortals is also the story of a brutal and bloodthirsty King Hyperion (Oscar-nominated Mickey Rourke) and his murderous army rampaging across Greece searching for the long lost Bow of Epirus. With the invincible Bow, he could overthrow the Gods of Olympus and become the undisputed master of his world.

As village after village is looted and obliterated with its able-bodied men massacred, a stonemason named Theseus (Henry Cavill, The Tudors) is unexpectedly drawn into the resistance. When his mother is killed in one of Hyperion's raids, he joins the fight against the invader but he has no idea he would become its leader soon. When Theseus meets the Sybelline Oracle, Phaedra (Freida Pinto), she has disturbing visions. She is not entirely sure of Theseus's integrity, but she becomes convinced soon that he is the key to stopping Hyperion's onslaught. With her help, Theseus assembles a small band of followers but he has also to deal with the gods who do not want to enter into the human affairs.

'Intrigued by the idea of turning Greek mythological stories into a compelling film'

Tarsem has assembled an enviable cast that also includes Academy Award nominee John Hurt (The Elephant Man, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows), Kellan Lutz (the Twilight saga), Luke Evans (Clash of the Titans), Isabel Lucas (Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen) and Stephen Dorff (Somewhere).

Tarsem says he was intrigued by the idea of turning the stories from Greek mythology into a fast-moving, dark and emotionally compelling film that could resonate with the viewers across the globe.

Scriptwriter brothers Charley Parlapanides and Vlas Parlapanides, he points out, used traditional Greek mythology as a jumping-off point, and created a story that begins when the gods of Olympus conquer their predecessors, the Titans, and imprison surviving Titans in a mountain.

'In our script, everyone has forgotten about the Titans, until one man, Hyperion, finds a dead Titan,' says Charley Parlapanides in the production notes. 'He decides that he will free the Titans and conquer the world. We pictured Hyperion as the Charlie Manson of ancient Greece. He starts a murderous cult and convinces people to believe in his plan. Not only is mankind in jeopardy, but the gods are as well.'

'Tarsem is a visionary'

Tarsem admired the way the Parlapanides brothers created an original narrative that remains true to the spirit of Greek mythology. 'We use familiar archetypes, but they're spun on their heads,' adds Charley Parlapanides 'At the heart of the story is a man who starts off as a nonbeliever and then goes on a journey that transforms him into a hero and a martyr.'

People worldwide will see the film as one man's journey from a non-believer to a believer, Tarsem says, and will also watch how the Gods have to take certain decisions that go against their conventional wisdom.

The producers of the film and the scriptwriters assert that Tarsem brought his own vision to the story and turned it into an unusual epic. The film's producers Gianni Nunnari (300), Mark Canton (300) and Ryan Kavanaugh (The Fighter) knew right from the start that Tarsem should have a completely free hand in designing and executing the film.

Kavanaugh, the CEO of the production and distribution company Relativity Media, calls Tarsem a visionary. 'He's brilliant, not just as a director, but as an artistic mind. This is a huge commercial epic,' the veteran producer says, ' but he never treated it like that was all it was. He considered every frame of every scene and knew before we started shooting the color of sandals every person had on and what their sword would look like.'

'If you are a god, there's no reason to look old'

Tarsem's vision for the film went far beyond simply making a Hollywood blockbuster version of a Greek myth, the producers point out. Shimla-educated Tarsem, who came to America at age 24 for graduate studies, says that the project served as a "Trojan horse," a vehicle to realize his own vision on a grand scale.

"I love reading Greek myths," he explained. "But I was not interested in making a film based on the originals and the script was also telling me something that I had not read before. I was intrigued by the relationship between gods and humans. So I thought, we could take some traditional tales and, like in Renaissance painting, use the mythology as the basis, but add things that are relevant to our time and I worked with the scriptwriters in achieving that."

The director also decided to make the gods look young. "Wisdom is implied with age," he says with a chuckle, "so Renaissance painters gave the gods the features of older people, but then painted a perfect body beneath that. In a film, you can't do that unless you make all the characters CGI. But my idea was that, if you are a god, there's no reason to look old. If I were up on Mount Olympus and I could look any age I wanted, I wouldn't want to have that white beard.'

Tarsem arrived for his first meeting with the producers of Immortals carrying a portfolio packed with reproductions of museum-quality paintings to illustrate his vision for the film. Tucker Tooley, an executive producer of Immortals, recalls that this first meeting wasn't quite what he expected but everyone was impressed with Tarsem's passion and vision.

'He brought in this big canvas and it looked like something you'd see in a museum,' says Tooley. 'At first blush, the painting looked very different from how we had imagined the movie, but when Tarsem started to explain, it really made a lot of sense to us.'

'There's a lot of testosterone in this film'

He proposed basing Immortals' visual profile on the work of Caravaggio, the unconventional painter of the Italian Baroque period.

Caravaggio had also inspired Tarsem in the making of Losing My Religion video. A rule breaker who pioneered the use of live models for religious and mythological subjects, Tarsem muses, Caravaggio 'employed a saturated color palette, dramatic lighting, and a feeling of dynamic movement and overt emotion in his paintings.'. His style broke from the more static work of the Renaissance and earned him both praise and criticism.

Tarsem worked closely with both the production designers and crew at length and over many months to recreate the luminosity typical of Caravaggio's work for the overall look of the film. "We call it finger-of-God lighting," says Tarsem. "It's very focused and seems to come from a far-away source."

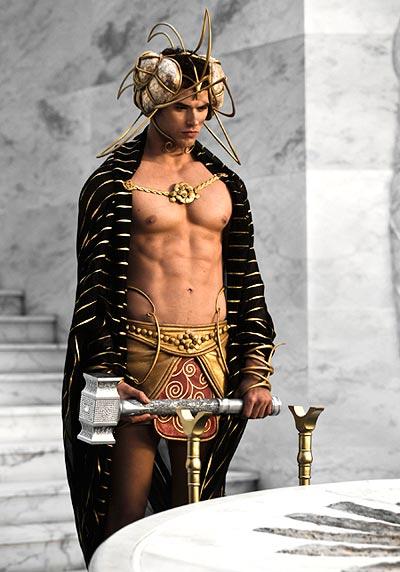

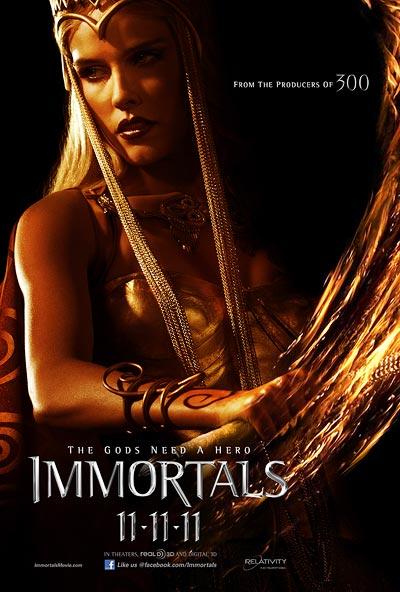

It is not only the stunt coordinators, the set designers but also the costume designers that had to come up with the unusual look for Immortals.

Costume designer Eiko Ishioka, who earned an Oscar for the costumes in Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula, is well known for her designs for film, theater, television and commercials. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Her iconoclastic worldview falls into the same imaginative territory as Tarsem Singh's, as per the producers of Immortals.

'We are not playing it safe with this film'

"As far as costumes were concerned, we decided early on not to go "Classic Greek"says Tarsem. "It would have been counterproductive to hire somebody like Eiko and then tie her hands. There's no point in telling her, 'Think outside the box.' She has no idea what a box is. She comes from a parallel universe."

"At the same time," he adds, "This is an action film. I had to make sure that she didn't make costumes that looked great but couldn't be moved in."

While Tarsem's creative drive and personal insights into the script began to transform the story, the producers say he never lost sight of the fact that Immortals is also an adrenaline-fueled action adventure. And the producers would help him pack the film 'with daredevil stunts, state-of-the-art effects, and the added excitement that only 3-D can deliver.'

'Tarsem was always looking for something that hasn't been seen before,' says Nunnari. 'I was often surprised myself. He is exploring a new way to bring images to the screen in a fantastic ride. It's young, it's fresh, it's original. And there's a lot of testosterone in this movie.'

Those who have watched the film's advertisement, preview shots and read a lot about it, know it is anything but a staid classical story-telling. 'It's in your face,' says Canton. 'We're not playing it safe. History is not safe. Mythology is not safe. And we're really not interested in safe.'