| « Back to article | Print this article |

Mira Nair: I find Pakistan very alluring

Against the backdrop of the Boston bombing, The Reluctant Fundamentalist added poignancy as it explores influences that make people who love America turn against it.

Mira Nair shares with Aseem Chhabra the complexities of her film.

It has been 25 years since Mira Nair made Salaam Bombay, her iconic film about street children. The film won the Camera d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for an Oscar.

Since then the Indian-American filmmaker, who lives part of the year in Uganda, has made fiercely independent films (Mississippi Masala, Monsoon Wedding).

Nair says her latest film The Reluctant Fundamentalist 00 based on the best-selling novel by Mohsin Hamid -- was the hardest film to make, primarily because she could not find funding for the project.

Five years of hard work, and many months of film festival touring, Nair is finally getting ready for the theatrical release of the film in India on May 17.

You have said The Reluctant Fundamentalist was the hardest film for you to make. There must be a sense of relief that you have finished it.

It is very rare that a director can sit back and say that it is exactly how I wanted the film to be. That is how I feel about the film. It's like childbirth when you forget the pain when you see your baby.

First of all, it was difficult on the creative level, just adapting the screenplay.

'The Namesake took a couple of months and this one took three years'

But you have done other adaptations, for instance, The Namesake...

The Namesake took a couple of months and this one took three years.

The first few months I spent talking to A-list writers in Hollywood and around the world. It was amazing to see the ignorance about the subcontinent and with that the arrogance that accompanies it.

A famous screenwriter said to me, 'Well first, you can't drag me to see a film with the world "fundamentalist" in the title. We will have to drop that word before I will commence.'

That immediately showed me his rigidity and his notion, because to me the whole reluctance of fundamentalism -- whether it is of money or terror -- is the most exciting part of it.

'It was not until I met Riz Ahmed that I knew I had found a man with all the qualities of Changez'

Those three words say everything about the book and the story.

Yes everything. And it's an unforgettable title. I went down that path and gave up on it, since I had much of my own agenda to bring to it.

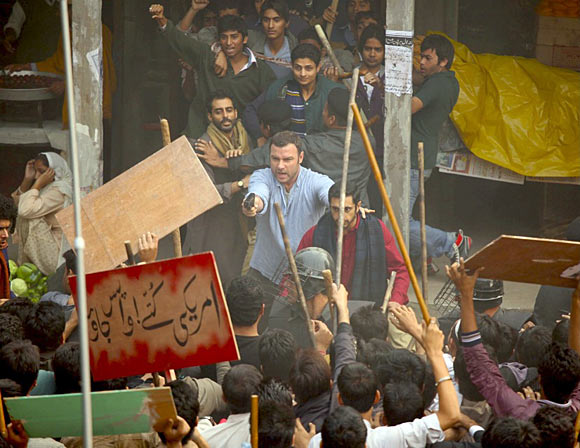

I wanted to amplify the family, the Pakistani culture that we share. I wanted to add the third act to the novel -- what (the film's protagonist) Chagez Khan does once he comes back to Pakistan. Yet I did not want it to feel like a 9/11 movie.

Because for me it is not. It's a coming of age story and a human thriller -- how does this young man find out who he is.

It's a film that re-complicates what we have been reduced to -- either being good or bad, black, brown or white. We are so many of those things and it is about these characters.

I think the script has been beautifully adapted by Ami Boghani, Mohsin Hamid and William Wheeler, who took it to the level of a thriller.

It took me a year-and-a-half to finding Changez. It wasn't simple. I started in Pakistan, because I find it very alluring, this sort of machismo beauty of Pakistani actors. But it is a complicated role. He has to do many things.

Visas alone were such an arduous process that I could not tell these actors to come on a whim and screen test with Kate Hudson (who plays Changez's love interest). It was not until I met Riz Ahmed that I knew I had found a man with all the qualities of Changez.

We started early in the process with a very well-heeled American investor. He was going to fully finance it.

Then after many discussions, he began to get nervous about the content, the politics of it. I got the idea when I got home one day and found a beautifully wrapped bottle of Chrystal Champagne.

I don't drink champagne, so it is still in the house. I called him and asked, 'Is this the kiss goodbye?' He hummed and hawed, finally said yes.

Then we went to other investors, but the only one who stood by me was the Doha Film Institute. Eventually they became the single investor.

Twice, we nearly started and then the funding collapsed.

It was also a difficult period of transition in my life. My son went to college and my husband went to teach for eight months in Kampala.

'I have been to Lahore five times, I find it very relaxing and restful'

People would have opened doors to talk to Mira Nair at least?

They would meet me, but for other things. A publication just said that Hollywood shut its doors on me. I actually never went to Hollywood, because I didn't want to subject myself to censorship.

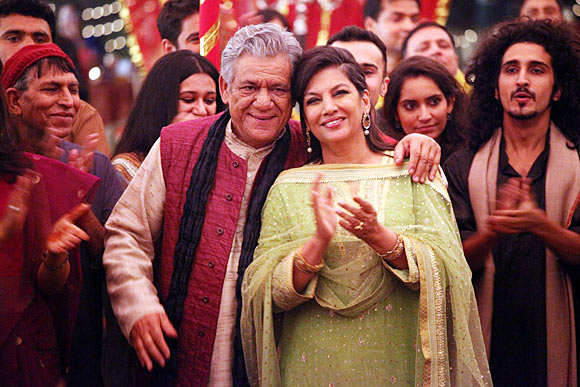

While there are a lot of similarities between India and Pakistan, you do a wonderful job of capturing the ethos of Pakistani culture, especially inside the homes -- the parties, the qawwalis, the Scotch whiskey drinking habit.

Yes the bootleggers and the language. I am dying to go back to Lahore. I have been there five times. I find it very relaxing and restful. I always go there and make music and songs.

'I am an authenticity junky'

How difficult was to recreate that world in Delhi?

I was very particular, because even though India and Pakistan are cut from the same cloth, there are differences. And I am an authenticity junky.

The way they speak Urdu -- 'Aap aa jayen.' They don't say 'aaeeye' in Pakistan. I was always taking notes when people would get excited about their bootleggers and the obsession with where their alcohol comes from.

You even show the poster for the film Bol.

Yes, we did a big thing about the screening of Bol. I wanted to make sure that it would feel right and truthful to the Pakistanis watching the film. We kept the slang how they speak in the universities in Pakistan.

'Kate opened the door, but she had forgotten to tell me that she was eight months pregnant'

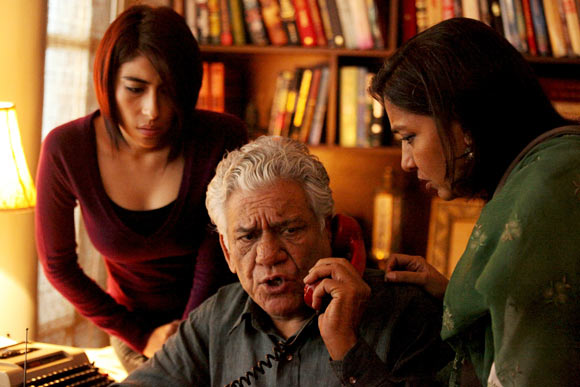

What did you see in the other actors -- Liev Schrieber, Kiefer Sutherland and Kate Hudson?

Liev, I have worshipped for a long time because I also watch a lot of plays. Anything he does I go watch. I love his voice, his gravitas and his stature.

I offered him first Kiefer's role (Jim Cross -- Khan's boss in a Wall Street private equities firm), but he called me up and said he wanted to have lunch since he wanted to play Bobby Lincoln (the American man Changez Khan engages in a conversation at a tea house in Lahore).

We had lunch and I knew he could play anything, short of Changez, and I said, 'Fine, play Bobby.'

Then I went to Kiefer. I didn't watch 24 until after I cast him, but I love his voice and his performances in whatever I have seen him in.

No one offered him this kind of a role -- a man with his mysteries. He's a political man and he said, 'It will be my honour to act in this film. We never see this story.' He added, 'We must see the mistakes of America.'

Before I met Kate I had done a number of rounds with many actors and she asked to see me. I went to her home. She opened the door, but she had forgotten to tell me that she was eight months pregnant. And I just started laughing because we were going to shoot in six weeks.

She started laughing as well. We rolled up on her couch and had a great time. I then went to India to start the shoot and it collapsed -- this was the second round.

Meanwhile, Kate texted me that she had the baby. Two months later without any entourage, she brought the baby and started shooting. She's a very brave actor.

'Music keeps me going in life'

Tell me about the music in the film. It is amazing. You worked with a lot of Coke Studio artists. You got Peter Gabriel to sing a song...Bol Ke Lab Azaad Hain Tere...

Music keeps me going in life and nothing inspired me more about Pakistan than its modern sounds. Kangna (the opening qawalli in the film) is from Coke Studio, but even before that I loved the qawwals Fared Ayaz and Abu Muhammad.

'I constructed the whole beginning of the film based on Faiz Ahmed Faiz poems'

'It was always my determination to show the film to Pakistanis'

You are planning to release the film in Pakistan and India. How do you think the Pakistanis will react to it?

I have shown it in six countries around the world and there are huge numbers of Pakistanis who come for the screenings. It was always my determination to show the film to Pakistanis.

'This film is an entertaining, yet has mysterious dialogue between an American and a Pakistani'

What do you want the audience to take from the film?

So often in this country we are made to feel like 'the other' post 9/11 -- even in New York City, where I have always felt at home.

This film is an entertaining, yet has mysterious dialogue between an American and a Pakistani. It makes you look at 'the other' in a different way. Because 'the other' is us, 'the other' is human.

People are now dazzled by the prescience of the film with the Boston bombings. They are wondering how do people who love America, are part of it, also turn against it.

When you see the film you realise that the path for a young man or a woman is fraught with all kinds of influences that we have to understand.