| « Back to article | Print this article |

'I don't want to work with newcomers'

In the first half of Karan Johar's conversation with Raja Sen, the filmmaker spoke about stepping out of his comfort zone, and being more honest as a filmmaker.

As the film-faffing continues, Johar discusses the problem of stars and image, the basic Bollywood screenwriting hurdle that should never change, and why he would never cast newcomers in his films.

Read on:

If having new people around you is so clearly broadening your horizons, why do you feel compelled to stick with a majority of the old-guard? Your film still stars Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol, the music is still by Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy...

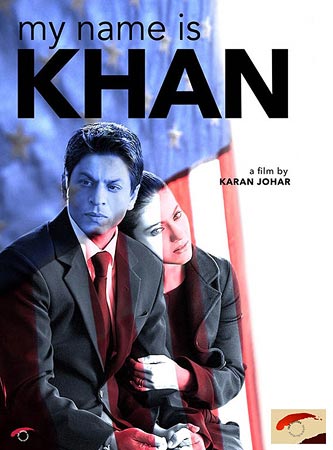

Some of those are the way they are, and the way they will be. I think if I yank myself totally out of my zone, it might affect me. Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy have also composed music that is completely different: there is no lipsync song in My Name Is Khan, it's all background. And the music is not Western at all, barring the fact that it's somewhere fusion based. Also it's got different voices, people I haven't worked with.

When I spoke to Shah Rukh, I said 'look, it's very important that you play even this character as a mainstream hero,' because that's one call that I took commercially. I felt he had to be an endearing character, no matter what. So if that takes bringing about a certain level of 'cutiefying' at times, or toning down the disorder in areas but still maintaining a regular pitch, I think it's imperative.

Yet you did research the disorder heavily and make sure you were being completely accurate?

We sent the script to the National Autistic Society, just to read the dialogues. Because there are a lot of things characters like Rizwan Khan don't say. They say things literally, so there are a lot of expressions they won't use. And then we sent the first bits of rushes to people, to see if we're doing okay. Because we needed to know. You see, it's such a varied disorder and there are so many strains of it, there's no one way of doing it. So one had to strike that balance between the projection of this character on mainstream celluloid and getting the facts right.

So, therefore, having Shah Rukh and Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy and Sharmishtha [Roy, art director] and Manish [Malhotra, costume designer] and all the people I've worked with earlier were also important. But I think all of them have been challenged. I don't think they've done something like this. We're very far away from the release, and one can never be sure, but the feeling definitely was that we haven't done this before. So either we could have totally screwed it up or maybe got it right, so that's something that I don't know. At all.

'We always get family genre right, because we know that the best'

While you do mention the need for his character to conform to Bollywood stereotypes, in a sense, and be an endearing hero figure, these are weighty subjects you are dealing with. Does this film then, for you, fall within the purview of serious cinema?

Oh, it's a serious film. No doubt about it. That's why it has a world of its own, its own beat. But I would say it's a drama, a quintessential drama which is definitely serious. There's nothing frivolous about it.

Don't you think we've stopped really tackling dramas in our cinema? Even our serious love stories seem trapped by the need to also be funny and sexy-looking. Don't we need to give in to the genre instead of playing it safe?

I just think that I have a certain pitch and tone. There are bits that are funny but they're not trivialising the subject matter at all. I think that one solid drama... yeah, maybe you're right, because how can you? How can your drama have song-pieces? A drama has a different kind of structure.

You have to realise something about Indian cinema -- no other cinema in the world has an interval, and one doesn't realise how drastic that makes your storytelling structure. That one gap in narrative actually changes the way we write our films. Which is our USP, it's what sets us apart -- but it's a huge deterrent. We would write films differently if we didn't have an interval but we have to, we have to.

So you start, you peak, you pitch, you stop. You build again, you peak, you pitch. So you have two peaks and two pitches and two finales in your film, which you don't realise, actually. Ninety percent of the problem with our scripting is that. On the global level, that's the problem we have.

Actually the half point of Khan, the film where one is trying to be careful, is not a peak-pitch point, it's just that something happens and we stop. It would have been seamless without it also, one has been conscious of that. But very rarely do you find that.

So then this writing around an interval means that we end up having to stick to the genres we know best, the ones suited to our mix and match masala genre...

In 90 percent of our films, you know when the interval is happening. You just know it. That means you've written it in a certain way, you've graphed it in a certain way. And that is our big problem, our big, big, big problem.

That's why we don't get most genres right. We don't get a thriller right, ever. Because we have to have that relationship running, that music coming. So we can't have a quintessential thriller, the way it's meant to be done. We can't get a drama right.

We can get comedy right because comedy can be a little sporadic in its narrative structure. And we always get family right, because we know that the best.

No Syd Field can tell you what to do with an interval. He might have a vague understanding of it, having viewed Indian films, but the three-act structure does not work for us. It just doesn't.

'My non-film friends have such strong opinions about actors'

Also, I feel, we aren't good at wrapping up. Many Indian films build up effectively enough but are completely let down by their second half. We falter and stumble so weakly in the third act...

And we always will. Because basically, you're trying to wind up everything because you've explained too much. If you don't explain everything too much, you won't feel the need to wind it up. The problem is that we have such little respect for an audience, while we are writing it.

We second-guess them in that way also. We feel that they won't understand this, they won't feel this. So you emphasise. And you over-emphasise and when you try to wind up that over-emphasis, you mess things up. Instead of just letting things be, we don't, we justify it, we analyse it, we say it out loud. Therefore that character becomes of such importance that you need to bring that track back and, some way or the other, wind up that track effectively, and you end up messing up your second half.

Also, we very rarely, as an audience, have a way of feeling that 'this happened. Why did it happen, we don't need to know.' Sometimes people behave in strange ways. You could be a neurotic man, you just are. You could be a great guy, you just are. Rani doesn't like Abhishek, she just doesn't. 'Why doesn't she, but?' Why do people ask this. 'He's such a great guy, he's such a nice man...' She doesn't. She's not turned on by him.

Do you see this then as a product of conditioning? The fact that we've reinforced these mother, sister, wife images too deeply, imposing them on an audience so much that they're now used to it?

Yes, conditioning, I suppose so. Because you can't take out the iconic status of the actor projecting it and yanking them into the realms of what is real. You just can't do it. You kind of feel that Shah Rukh is a noble man, and Rani is a quintessential good girl. You'd be surprised at how strongly an audience has made up their minds about the kind of person you are, and sometimes they can just reject you because of your off-screen persona.

India does that a lot. You know that some audiences really love Salman, that Aamir just qualifies intelligence. He can validate anything. You watch Ghajini, and even if you don't like it, you feel that he's saying something in Ghajini also, because he's Aamir Khan. You know? 'Somewhere he must be making a comment on violence.' You'll give it that kind of validation.

Whereas if you come across frivolously, you can do what you want but you'll not be able to come across as a noble, Gandhian character.

My non-film friends have such strong opinions about actors. As people, not as actors. 'He's always sleeping around.' How do you know? Are you under his bed? 'He's cheating on his wife.' How do you know, are you the wife? They have these opinions, they just 'know it. ''We should be culturally different'

And that doesn't detract from their enjoying the said actor's work on screen, right?

It tends to become a part of the actor's persona, which again doesn't happen anywhere out of the country. I think we're a very sensitive people, as a nation. I think we have an interval in our souls (laughs), we pause sometimes and think too much, and that's why we like that in our films. We tend to be very very judgemental about humanity, much more than other cultures, other nations.

About that interval point, now that we are making films between a 100 and 120 minutes long...

Yeah? Who is? (laughs) Who are these people? You aren't talking to one!

Do you think we can start thinking about doing away with the interval?

Well, the diaspora audience doesn't stop the film at all. They don't have an interval. They take their own interval, they'll go out and come back. It's the most annoying thing to watch it with them, because they'll walk out at the worst time and you'll keep wishing they hadn't.

But no, I think the interval is a part of our culture in a certain sense, and I don't think we should ever do away with it. There's just a magic in coming out and talking about the film. Where else in the world do you talk about first half/second half? Either a film worked for you or it didn't. Here we say first half was good, second half dropped. They'll look at you in the West like you're mad.

And that's the way it should be. We should be culturally different.

Coming back to actors and their images creating perception issues, especially when it comes to casting them in some light... Don't you think that just intensifies the trouble that we have a tiny pool of stars that all filmmakers are clamouring to sign?

Totally. We have five actors, four actresses, three directors, three art directors, four choreographers. So when you're starting a film you don't know what to do. And you go about saying okay, lets give this one a shot. And out of the four actors, one of the actors has a problem with that choreographer because he's new and he can't dance well and so there are internal problems... it's all very, very limited.

You have 20 working people in the industry whom you can work with. So then? Then that brave attempt has to be made of taking somebody new, and then you have to work with a new actor, which I don't want to do. And then that whole process starts again.

You do bring in a lot of new directors, though.

I've been accused of never launching a newcomer. I say I do even better, I launch new directors. Which is far more important for me. I don't even want to sound cliched and say when the script comes, I'll work with a newcomer. I don't want to work with newcomers, I have no interest in it. I like to work with stars. With people who made their mistakes and have now evolved.

I don't want to play Professor Higgins to newcomers. I want to have an interaction, not a teaching. I don't have an inherent desire to teach, I feel I have things to learn. So I have absolutely no interest in going down that path.

But I love interacting with new directors, because I really believe that they'll teach me a helluva lot. Like I know so much about films from these new kids making movies, and whether they make a good one or a bad one, they teach me a lot.

'I can't make a low-budget small film ever'

And that same learning from a fresh approach doesn't happen when you tap into new actors?

There can be nothing more frustrating than working with a non-actor. The few moments that I've lost it on sets -- and they're very few because I'm relatively calm -- are when I have a bad actor. I don't think there's anything worse. I'd rather slash my wrists than work with a bad actor.

I can't tell you how annoying it is. You're used to a certain standard, and now you can't work with them. And I really have no desire to. Maybe when I'm 50 and nobody wants to work with me then I'll say, 'now I'll make my newcomers film,' but not now.

Agreed, but a lack of experience doesn't mean a lack of talent. In any case, there is a bigger talent pool out there beyond the obvious, the five heroes and four heroines. There are talented, experienced actors who aren't getting the platform they deserve.

And I'm actually working with a lot of them, as a producer or a director. I mean the ensemble of Khan is full of people who are doing a lot of great work in all kinds of films. Besides the lead actors, there's a whole ensemble full of interesting people in the film. And I've enjoyed working with all of them, and I want to work with all kinds of actors. But my main cast will always be my main cast.

What about size and scale? Do you ever see yourself making a smaller film?

I don't know. I can't right now, I wouldn't know what to do. The films I'm producing are small films. Wake Up Sid, I wouldn't have been able to make, it's been shot in a really tiny space, the size of this room, and I wouldn't know what to do. But I've learnt a little bit on Khan, how to make a small space look cinematic, so I'm learning. But produce, I'd love to. I wish somebody had given me the script of A Wednesday. I loved it. That was one small film I wish I had produced.

I would love to produce all kinds of tiny films on a script level, and then project them. To market a film is now something I may understand the world of, how to put it out there. And I would love to produce it, to nurture the talent and put it out there. But direction, no. I can't do it.

Not yet, you mean.

No, maybe not ever. Yeah, maybe that's my big sweeping statement that I can't make a low-budget small film. I can't do it.

Because as a viewer, it would be fascinating to see your kind of filmmaking trapped within heavy constraints.

And I'm really happy that you might expect that but (laughs) I'll be sad to report that I won't be able to deliver. And I know what you mean, it would be interesting to see me try. But you'd hate the film, because even if I made it, it'd be the most wannabe thing I'd ever do. To try and downsize my vision. And wannabe is something I can't do. I can make sh*t, but I wouldn't want to do anything that's wannabe.

Watch out for Part 3 of the conversation with Karan Johar, where the filmmaker talks about himself as a producer, new ideas, originality, and his Stepmom remake.