Photographs: Eric Gaillard/Reuters Aseem Chhabra in New York

No wonder one of the first scripts he worked on was about an eatery in Hamburg -- partly inspired by the life of his restaurateur-actor friend Adam Bousdoukos.

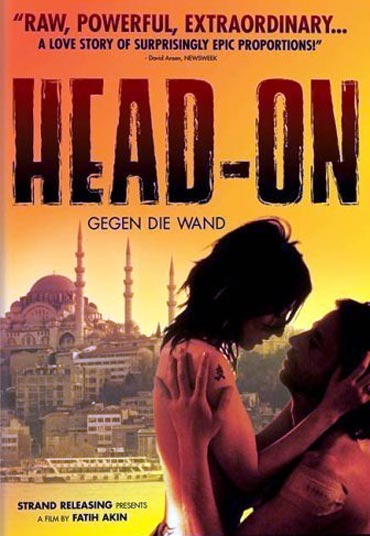

But then other projects took precedence -- including Akin's 2004 film Head-On, winner of the Berlin Film Festival's prestigious Golden Bear prize.

The intensely disturbing and violent Head-On, won Akin admirers around the world -- from established filmmakers to lovers of world cinema.

In 2007, Akin returned to his favourite theme of Germany's multiculturalism with The Edge of Heaven -- a complex drama about adult children and parents, layered with the themes of forgiveness and redemption. The Edge of Heaven won the prestigious best screenplay award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Having made two serious films, Akin was now ready to work on something different. Soul Kitchen is that film -- a delightful comedy, capturing his love for food, the restaurant business and music.

The film stars Bousdoukos, the original inspiration for the film. Winner of the special jury award at last year's Venice Film Festival, Soul Kitchen opens in New York on August 20.

Akin, who is just 37 years old, spoke to Rediff.com contributor Aseem Chhabra in New York City about his new film, why he works in Hamburg and his friendship with Indian director Anurag Kashyap.

Was the process of making a comedy easier and less demanding than intensely serious films like Head On and Edge of Heaven? In fact isn't filmmaking difficult, no matter what?

Yeah, yeah, but I think comedy is more difficult. The making of this film was much trickier than the making of the other films. Here the technical and logistical aspects made it more difficult. There were so many characters.

In Head On we had two characters. You have more characters in Edge of Heaven but at any time only two appear.

In this film there would be six, seven, sometimes eight characters and lots of extras.

At times we had eight speaking characters not in one scene, but in one shot and how do you manage it that everybody gets the necessary weight that they need, but without overrunning somebody or forgetting a character.

That happened one time during the shooting. We saw the rushes and realised that one guy had not said anything. We had to reshoot.

Usually I go to the set prepared and I know what I am doing. I have done my rehearsal with the actors, so I know the camera angles and what the actors would do.

This time I made preparations, but threw everything away and re-wrote a lot.

'The hero is always under pressure'

Image: A scene from Soul KitchenTo make it very enjoyable, and to make it look like throwing water over stones, that was very hard.

You have said how you had to move the camera to go with the energy of the characters.

It also depends on the material. The material of the other films was different, so they needed another rhetorical language.

But for this film we had to make, speed, speed, speed, go on and on, don't stop, don't stop.

So even when the actors do not move, the camera has to move. There are very few moments when there is no pressure and the camera sits still.

The film is about pressure. The hero is always under pressure.

And he has the back problem. I believe that is autobiographical, since you once suffered from slip disc. That must have been so painful. Throughout the film Zeno (played by Adam Bousdoukos) is in pain. You can feel his pain.

We did not shoot chronologically. But we separated the whole script in stages for his back pain. So when we had rehearsals, we would say -- 'Here you are on stage 1, now you are stage 3, now you go back to stage 2 again, where you are feeling a bit better.'

And we had a coach for the back pain and Adam learnt the various stages like that.

The film has a great soundtrack. The music obviously it has to go with the name Soul Kitchen. Did you grow up listening to this music?

It was not meant as the favourite music of the director, but for this material this seemed to be the right music.

It's the Hamburg sound. They listen to a lot of soul music in Hamburg, much more than Berlin, where it is more electronic music.

Hamburg was occupied by the British and the Americans, they had their (military bases there and they brought their music.

We had a vision to have the film like a DJ set, a good DJ mixes up the tracks and the audience does not realise when one track has changed. That was the challenge to mix it up and the scenes move naturally.

There is one scene where we show how the time is passing -- there is a soul track and then there is one moment the DJ shifts the music channel, the music changes and we are back in the story again.

I am very proud of that moment. The whole structure of the film becomes a DJ set.

'Everybody has the same heart'

Image: A scene from Soul KitchenMunich is the centre of the film industry in Germany. When Germany was divided, everything moved to Munich.

Since the (Berlin) Wall fell down, the centre has partly shifted to Berlin. Hamburg is an independent place for filmmaking.

But you continue to make your films in Hamburg.

I have my life there -- my parents, my wife, my kid (his son is four), the family of wife, my brother, my production company. So this social life keeps me there.

I cannot move to Berlin or New York.

But then I am very supported by the city. There's one state television station in Hamburg and they partner with me.

I can go there on my bike and they ask, 'How much money do you need? Okay, a million.' They get television rights for seven years. So there is no need to go somewhere else.

Your films reflect on the multiculturalism of Germany. Your earlier films focused on Turkish people in Germany. Now Soul Kitchen is about Greeks in Germany. That is a conscious effort you make, right?

It's part of my being and I am an auteur filmmaker so I settle the heroes closer to my world and to my biography, than to show lives of white Germans.

I did that in Edge of Heaven with (veteran German actress) Hanna Schygulla.

It was difficult to write, but then I realised that one needs to forget the differences.

Everybody has the same heart. She loses her daughter, the pain she has, everybody understands that pain.

There are German filmmakers who have white German heroes, but I don't have to do that.

If it was a foreign script, I would do it. After all the white people live there, they are not a minority.

It's interesting that you refer to Germans as white people...

I mean they are white.

As a person of Turkish heritage and you were born in Germany, do you call yourself brown?

I am red skin (laughs).

'I love Bollywood'

Image: A poster of Head OnWhat do you think you are doing with cinema in a small city like Hamburg that people admire your work?

When I go to the movies, I am interested in travel. I love Indian films, I love Bollywood, but I prefer work of someone like Anurag Kashyap. And not just his films, but he wrote Water.

I learnt a lot about India from that film. I have not been there ( to India) yet. But cinema can be like traveling.

It's same with Chinese cinema. There are films like Hero and Crouching Tiger, but I prefer films like Still Life Chunking Express is about style and a Hong Kong mentality.

But to see a film like Still Life or Beijing Bicycle -- you learn a lot about China.

I am interested in how social life somewhere else works, how the relationship between men and women work in the Arab world or in India.

I think I do the same with Germany. I don't think I am very special. There are people like me all over the world and they are interested in life in Germany.

Look at Aki Kaurismaki. He makes his films in Helsinki, where's that (laughs), but he can tell so much about his own, and also about the Finnish mentality.

I would love to come to New York and do a film about a cab driver from Bangladesh.

How do these people live, where are their families?

When you have a Bangladeshi guy, driving a rich Jewish lady to 47th Street, what is that counter culture clash like?

I am very interested in that type of storytelling.

You mentioned Anurag Kashyap's name. He has told me that you both are good friends and he admires your work. Have you seen his films?

I haven't seen all of his film. He's my brother; he's really like my brother.

We met in Venice last year. He was on the jury.

We became close like brothers. I met him for two days and saw some of his films. But it feels like I know him for all my life.

Did you see Dev D?

Yes I have. He has sent me some more films. He brought me closer to India in a way.

I really like his style -- his visual sense, his humanity in the film. His work is like a brother to me.

I wish I could do a film with him one day. I don't know how. I write and he directs or we write and direct together.

'Anurag Kashyap is like my brother'

Image: A scene from Edge of HeavenBecause I was growing up in an occupied country and I am a kid of the 1980s, the most powerful impact -- in addition to Hollywood films -- was the Nouvelle Vague from France, the Neorealism from Italy, Ingmar Bergman's works, Asian cinema, Iranian cinema -- although that came late into my life.

I read that Edge of Heaven was inspired by Iranian films.

Yes. I was watching a lot of Iranian films at that time and I was very impressed by them, and also Turkish films.

I saw a beautiful Turkish film in the 1980s by Yilmaz Guney --Yol.

Yeah, it's the best film, it's beautiful. All of Yılmaz Guney's films were beautiful.

Many years ago a repertory theatre in New York showed Yol with Midnight Express -- two completely different films, although both deal with prisons in Turkey.

There's an interesting story about (Greek-American filmmaker) Elia Kazan. When Midnight's Express came out, The New York Times asked him if he would like to go to Turkey and visit Turkish prisons and see if it is right or wrong in the film.

So Kazan went to Turkey. And some leftist people said, 'You must visit Yılmaz Guney who was in prison.'

He made four films sitting in prison. He would give instructions to his assistant how to shoot the films.

Kazan visited him and they became friends and he asked Guney, 'Why do you want to be out of prison? You are so powerful here.'

Guney said he felt safer in prison. 'Outside they want to kill me,' he said.

One day I am going to make a film on Yilmaz Guney.

What are you working on next?

I am writing two films -- one is on the boxing industry in Germany.

There's a Turkish promoter who is in a joint venture with (the well-known American boxing impresario) Don King. He has three champs -- two of them are from Cuba. He arranged their escape from Cuba. He trains them in Germany.

Castro was really mad about it. And the other is a period piece.

Meanwhile I am trying to finish a documentary that I have been working on for five years. It's called Pollution Paradise.

It's about a pollution camp in Turkey in a village from where my parents come from. In the middle of the village they built a wild trash camp and they killed the village.

It is about the fight of the village against the government.

Comment

article