| « Back to article | Print this article |

The Godfather: Celebrating 40 years of cinema's first family

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the most eulogised film in the history of cinema -- The Godfather.

If you know what's good for you, Charles Foster Kane, move over. That's it. Keep those hands where I can see them and slide out of that top seat, slide out nice and easy. There, that's a good man.

While sacrilegious to suggest that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane, the most eulogised film in the history of adjectives, doesn't belong at the very top step of the all-time cinematic pantheon, I feel it is time to clear the throat and state the truth. That a certain film released 40 years ago, to the day, cast a far greater shadow on cinema's firmament, and indeed, its history.

This was a more ambitious, more influential, and infinitely more viscerally rousing film than Kane, and while two masterpieces ought not be compared, or ranked, the fact is that they are, and the Citizen is routinely called the greatest ever English-language film.

However, given that this is a matter of opinion and impossible to empiricise, all I can say is that if you disagree, you should be sleeping with the fishes.

Because that top step belongs to the Corleones.

The Godfather: Celebrating 40 years of cinema's first family

The Godfather released on March 15, 1972.

We must all gratefully doff our Homburgs to director Francis Ford Coppola, who vitally showed both a slavish commitment to Mario Puzo's sweeping novel as well as a rebellious defiance toward a studio skeptical about his vision.

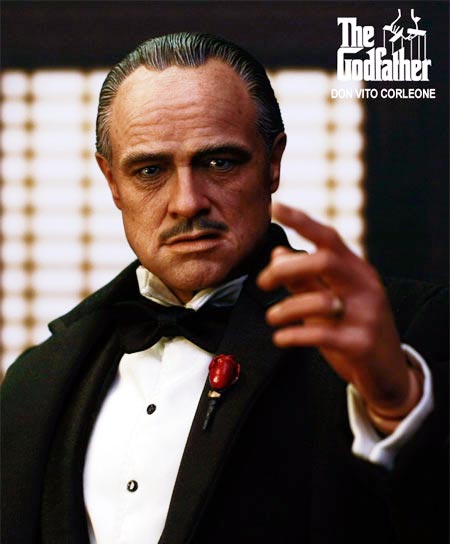

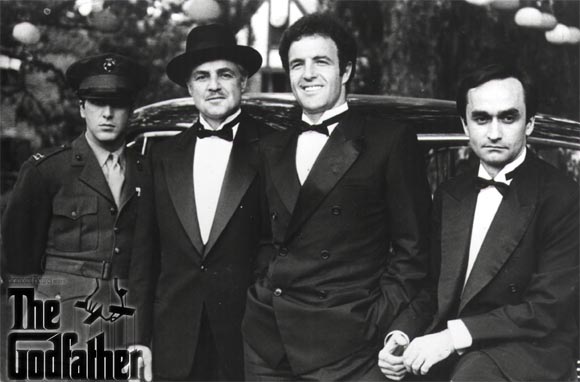

The casting, for example, was all Coppola, while Paramount Pictures tried to field big stars in the roles. Paramount didn't want Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone, thought Robert Redford should play Michael Corleone, considered Paul Newman and Steve McQueen for the part of Tom Hagen, and didn't think much of this little-known Al Pacino guy Coppola was fielding so strongly for the lead role.

Coppola stuck to his guns throughout, despite being a young director given a massive mainstream break. For part of the shoot, he was shadowed by an understudy director sent by the studio, all set to step in and take control of the film if Coppola messed up.

The Godfather: Celebrating 40 years of cinema's first family

What changed the studio's minds, about both Coppola and Pacino, was the scene in which Pacino's Michael shoots two people dead in an Italian restaurant, Sterling Hayden's Captain McCluskey and Al Lettieri's Virgil Sollozzo.

A breathlessly paced scene coiled as tightly as a Hitchcock timebomb, it involved a hastily trained Michael frisked for weapons, being escorted in the wrong direction before being turned around towards the originally planned eatery, making conversation with the two men he loathes most in the world before excusing himself, retrieving a hidden gun from a bathroom and then returning to shoot both of them dead, and then bolting from the place.

It isn't hard to see why the studios began to breathe easy. Pacino's remarkably immersed in the character, with his every deep breath, every glance a moment of silent, internalised intensity, his shaky, frantic urgent nerves making the scene quiver with tension.

Coppola steadily tightens the tension like a noose, and it is only after Michael flees the scene that you realise you'd forgotten to breathe for several minutes.

The Godfather: Celebrating 40 years of cinema's first family

Yet, there had been other gangster movies, many more violent, and several as gripping.

What sets Coppola's Godfather apart, in my opinion, is the way he built genuine empathy for his mafia men, creating highly nuanced characters with significant psychological details.

It is a film about family, and Coppola gives us men who are both unscrupulously gun-weilding and fiercely loyal, prizing the clan over all else. The clan, and the cannoli.

Like Michael said, they learnt "from the philanthropists, like the Rockefellers. First you rob everybody, then you give to the poor." Don Vito is thus both protector of the weak as well as noble paterfamilias of the criminals, both angel of mercy and death.

It's all business, not personal -- except these are real people, and when they take it personally, they die. Like Sunny Corleone does when ambushed at the toll plaza.

The Godfather: Celebrating 40 years of cinema's first family

The Godfather begins with a wedding, it ends with a christening.

I have written about the film before, of course. Four years ago, when Coppola brought us his trilogy to fantastic, hitherto unexperienced quality with a brand-new DVD box set, I tripped back to my most vivid cinematic recollection as a child, in a piece called The father of all.

Then, in my feature on The Best Films Of The 70s, it was an obvious, automatic inclusion.

There is much that has been said about The Godfather, but all I have to say about it, on its fortieth birthday, is that it is a film to be grateful for, and a film we should revisit all over again.

For it begins with a wedding. It ends with a christening. And in between lies everything.