Photographs: Ganesh Balachandran

Many books have been written on star composer A R Rahman but surprisingly, his official biography is only just out. Penned by British television producer Nasreen Munni Kabir -- who has made documentaries like Movie Mahal, In Search Of Guru Dutt, How to Make it Big in Bollywood and The Inner and Outer World of Shah Rukh Khan -- the book is titled A R Rahman: The Spirit of Music.

The book, which is a conversation between the author and Rahman, captures Rahman's life before and after his international stardom.

We produce an excerpt about his early life:

NMK: I believe it was your father, R K Sekhar, who gave you your first music lesson. He is still regarded as a legend in the Malayalam music industry. How did he come to join films?

ARR: He began by composing for the theatre and then for the cinema. My father was a composer, arranger and conductor and had worked in over a hundred films. He played the harmonium and piano. My father used to be so busy that he would sometimes do seven or eight recordings a day.

Yes, he did give me my first music lesson. But I only remember it faintly. I was four.

NMK: Where were you born, at home or in a hospital?

ARR: My parents lived with my maternal grandparents in a rented house on Mount Road in Pudupet in Chennai. I was born there on 6 January 1967, in the morning - at 5.50. It was a Friday. There was no midwife assisting the birth, and my grandmother and father were by my mother's side.

I was told that my father was very happy because I was the first son in the family, so he distributed sweets to everyone. You know most Indian parents are keen on having a son. [smiles]

My mother said I used to suffer from tummy problems and until I turned four, I believe, I was a frail child.

NMK: Did your mother describe to you the kind of child you were?

ARR: Apparently I was a bit of a loner, didn't have many friends and stayed at home most of the time. She told me when I was five, I would lock myself into a room and play the harmonium for hours - the quiet type, soft natured. [both laugh]

Some months after I was born, my father had enough money to buy a house on Habibullah Road, which is in a Chennai neighbourhood called Thyagaraya Nagar. We moved there with my maternal grandparents. That's where we lived for twenty years, from 1967 to '87. My grandparents used to pamper us children.

I have three sisters. The eldest is Raihanah, who is also a composer now. Her son Prakash is doing very well composing for South Indian cinema. Then there's Fathima and Ishrath, my younger sisters. Fathima is the director of KM Music Conservatory, the music school I started in Chennai. My youngest sister, Ishrath, is a singer and has her own music studio. We're hoping one day to release an album with all the family members.

Having my sisters around when I was young helped me greatly in dealing with the social isolation and the absence of a father. When I was growing up, they gave me so much love and it's the same even today.

Excerpted from A R Rahman: The Spirit of Music, Conversations with Nasreen Munni Kabir, OM Books International, Imprint: Spotlight-An Imprint of Om Books International, with the publisher's permission, Rs 495.

'My grandfather was a bhajan singer in a temple'

Image: AM Studio in Chennai. March 2010Photographs: Peter Chappell

NMK: What kind of a house did your father buy in 1967?

ARR: It was a three-bedroom house made of concrete. But it wasn't solidly built. To cut costs, builders would use saltwater instead of clean water when they made the clay roof tiles, so when it rained, the roof would leak. The rain used to pour down on our heads, and sometimes even the street water would flood the house because it was built on low land. We had to use every pot and pan that we owned to collect the rainwater.

NMK: Goodness! And your paternal grandparents? Did they live with you too?

ARR: No, they didn't. I don't remember them very well. But I know my grandfather was a bhajan singer in a temple in Mylapore in South Chennai.

NMK: It's amazing to hear that your grandfather sang bhajans, Hindu devotional songs. Because many will agree with me that your way of singing qawalis, Muslim devotional songs, stands apart.

Do you remember anything about your grandfather?

ARR: I have no memory of him at all. I only remember going to his funeral when I was about four.

NMK: And what sort of person was your father? Did he influence your music?

ARR: He was a great influence. I used to love listening to his music. Our home was full of music. No one I knew at the time had six keyboards in their house. What a luxury! [smiles]

My father was the first composer in South India to have bought a Japanese synthesiser. And as a result, he even got a free ticket to travel to Japan, but never went there because by that time he was unwell.

'My mother managed to run the house by hiring out the musical equipment that we owned'

Image: With mentor and friend Mani Ratnam. March 2010. Their Collaboration began in 1991 with AR's first film Roja, released in 1992Photographs: Peter Chappell

NMK: There seems to be some mystery surrounding your father's death. What actually happened?

ARR: He was working so hard that his health suffered. My father had stomach problems. The only memory I have of him is seeing him lying on a hospital bed. From early 1974 to September '76, he was in and out of so many hospitals. No one knew why he was in such poor health. He had to undergo three stomach operations.

My mother visited many spiritual healers because she wanted my father to try spiritual healing. He was in great pain. But he never really believed in spiritual healing and perhaps it didn't help him.

It was during that time that we first met Karimullah Shah Qadri, a Sufi peer [saint], who became a great influence on the family. He helped us to come to terms with many things. He was a huge support.

My father was not destined to live long and died on 9 September 1976. He was only forty-three. Because he had died of an undiagnosed disease, some people believed that his rivals used black magic on him. That's how the rumours spread.

NMK: How old were you then?

ARR: I was nine. His death was an emotional blow for the whole family. His first film as composer was released on the day that he died. A Malayalam film called Chottanikkara Amma with Prem Nazir and Adoor Bhasi. It became famous for his music.

My father didn't leave me a castle or anything, but he did leave me some musical instruments. And most importantly he left me the tremendous goodwill of musicians. Some of the musicians that he worked with are still playing with me.

NMK: When did you first decide to become a musician?

ARR: I didn't decide, in a way, I was forced to. Since my father was the only breadwinner in the family, we were faced with a lot of money problems after he died. We had to find a way of surviving. For the first two years, my mother managed to run the house by hiring out the musical equipment that we owned - keyboards and combo organs. They were very popular in the 1960s to '70s.

In 1978, when I was eleven, I started working as a roadie, setting up our keyboards for other musicians. I was studying at the Padma Seshadri Bala Bhavan, but couldn't go to school every day because I was the only one in the family who brought home any money. My sisters were still very young. I developed a kind of complex about being absent so often from school. At one point, I had to take a year off from studying, but when it came to the board exams, I still managed to get sixty-two per cent. [smiles]

'Arjunan Master gave me my first job and a token salary of fifty rupees'

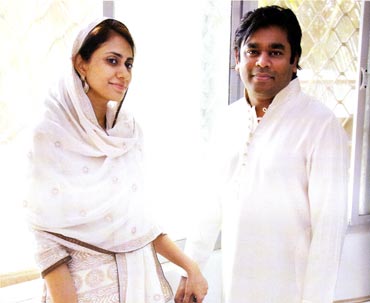

Image: With Saira in their Chennai home. March 2010.Photographs: Peter Chappell

NMK: Did you study music while you were working as a roadie?

ARR: Despite all the problems, my mother made sure I did. Her name was "Kasturi," but she later took the name "Kareema Begum." She has always been a pillar of strength and never let us children ever feel the absence of our father.

Things were changing. A year or so later, the musicians who couldn't at first afford to own keyboards started to buy their own gear. So people stopped hiring our equipment. That's when my mother said: "why don't you learn to play the keyboards?"

So I started working as a keyboard player. I was about twelve. A friend of my father's, the Malayalam composer M K Arjunan, who is fondly called Arjunan Master, gave me my first job and a token salary of fifty rupees. I had to operate a record player for a film.

For almost ten years, from 1979, I worked as a session musician with almost every music director in the South. I played the keyboards in the film orchestras of many famous and popular composers, including Mr Ilayaraja, Raj-Koti and the Kannada composer Vijaya Anand.

NMK: Did you go to school at the same time?

ARR: Yes, but my timings were so crazy that I was forced to change schools because I couldn't make it to class. In 1983, I left my first school and enrolled in the Madras Christian College. I studied there for just under a year. Then the Telugu composer Ramesh Naidu offered me a year's work as a keyboard player, and I decided to stop studying altogether. I must have been about sixteen.

The really busy work period started from about 1988. I was working double shifts, playing the keyboards for film music and jingles. I was working with Raj-Koti from 9 in the morning to 9 at night, then I would take my car, load all my equipment, and drive to another studio called Picture Productions where it would be jingles. I would finish at 4 the next morning, come home, sleep for four hours and return to the studio. I ate between shifts. That's it [laughs]

'I wanted to be a computer engineer when I was a kid'

Image: At the audio launch of Enthiran (Robot 2010) with director S Shankar, Kalanithi Maran and RajnikanthPhotographs: Courtesy - S Shankar

NMK: Were you well paid?

ARR: Yes, because I was also a music programmer, which meant I earned a lot of money. I started at 200 rupees a shift, and ended up getting 15,000 a shift.

It was hard work but the money helped to support the family, and allowed me to buy more gear.

NMK: Do you regret missing out on a carefree childhood?

ARR: I did miss out on many things, but I don't regret it. I didn't have time for sports or holidays, or the kind of things people spend their money on. We didn't miss those things because we didn't know they existed anyway. But I did feel insecure about leaving school at sixteen. That's young. If you aren't formally educated, no one will let their daughter marry you. [smiles]

NMK: Do you visit your old house on Habibullah Road?

ARR: Yes, I went back there recently. It felt exactly like Cinema Paradiso. I had the soundtrack of that film in my head as I drove through the lanes of Thyagaraya Nagar - it was home for the first twenty years of my life. Everything has changed. All the hutments are concrete houses now.

I went there because I had wanted to visit a friend. Unfortunately, I didn't know that he had passed away the year before. I met his mother and she asked me: "What are your kids doing?" "They're learning music." "They should become doctors." "No. My kids want to learn music." "Well, why not? You've won many awards, right?" [both laugh]

Musicians in India still don't seem to have enough social status. At least that's how the older generation see things. They don't seem to recognize musicians as belonging to a full-time profession. But it's cool to be a musician, if you're famous. [smiles]

NMK: Was working as a session musician any fun?

ARR: It wasn't exciting because the music was quite traditional. I wanted to be a computer engineer when I was a kid. Electronic gadgets and technology fascinated me. When I managed to save money, I bought some modern kit, then I had fun playing music.

Comment

article