Bollywood's villain Bob Christo may have passed away but he has left behind much to remember him by. Besides a large collection of movies, the civil engineer from Sydney, Australia, also left behind his autobiography, which was released after his death.

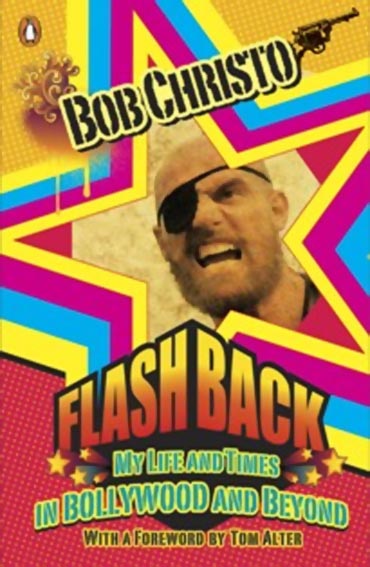

In the book titled Flashback: My Life and Times in Bollywood and Beyond, Christo shared his filmi experiences, and his life.

Here's an excerpt from the book:

Meanwhile, I had a good look at Bombay city, doing a lot of walking which helped me find my way around pretty soon. On the second day in Bombay I saw a group of people filming in the street and I stopped to watch. After a while, they started winding up their work, shaking hands and kissing one another. I heard them saying that the shooting part of the film was over.

I started to talk to them and found out that the director's name was Prem Kapoor. I told them that I had also worked in movies; I'd just worked for a big Hollywood film in the Philippines a few months ago.

Prem Kapoor invited me to come to their hang-out in a tea house on Veer Nariman Road near Churchgate station in the evening. I went there and met Prem and some others of that group. I had heard that anybody with the name Kapoor was big in the Bollywood film industry, but Prem Kapoor explained that he made only documentary films. 'This joint's a meeting point for art film-makers and documentary producers.'

I asked him if anybody could help me meet Parveen Babi. I described how I had found the Time magazine in Rhodesia with a big write-up about the Indian film industry and Parveen Babi. Prem said he'd tell his workers and friends, and sooner or later somebody would introduce her to me. From them on I used to drop by at that tea house regularly and listen to them talk about their film stories.

A few days later, one of the cameramen who came to the tea house occasionally spoke to me. His name was Zuber Khan. He and a sound man, Chakravorthy, who also used to come there, worked for big feature movies for BR Chopra Productions. He told me that there would be a 'mahurat' for a movie called Burning Train the next day. 'Parveen Babi is one of the heroines.'

I asked, 'What is a mahurat?'

'That's an inauguration. I'll pick you up tomorrow at 9 am at Andheri and take you to Bombay Central station. I'll introduce you to Parveen Babi.'

'Great, 9 am at my place.'

Excerpted from Flashback: My Life and Times in Bollywood and Beyond by Bob Christo (with a foreword by Tom Alter) Penguin Books India, with the publisher's permission, Rs 399.

Parveen Babi: I don't wear make-up when I am not working

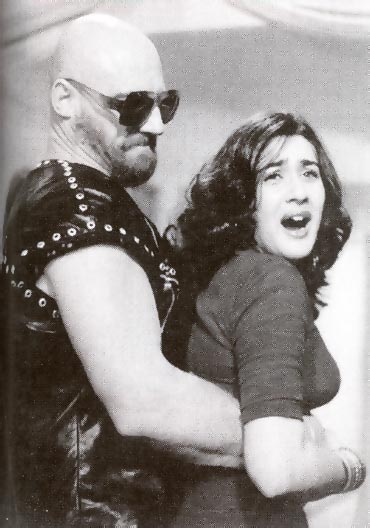

Image: Raj Kiran and Bob Christo in Star (1982)When we arrived at Bombay Central railway station the next day there was a train on the first platform and a lot of people carrying boxes and cameras and megaphones. Zuber ordered me to stand where I was, in front of a pillar. 'Parveen Babi will come here.'

After about fifteen minutes a lady stopped in front of me and said, 'Hallo, I'm Parveen Babi.'

I looked at her for a moment and then answered, 'You're not Parveen Babi!' Pulling the Time magazine out of a pocket, I pointed at it and said, 'This is Parveen Babi!'

The lady laughed and retorted, 'In the magazine I'm in make-up and full get-up. Normally I don't wear make-up when I am not working. Now, before the mahurat shot, I'll have to go for my make-up first.'

I apologized and said, 'Actually I was only pulling your leg. I've been admiring your beauty. Ever since I read this magazine I've wanted to meet you personally. I'm really happy to meet you like this. I've been carrying this Time since I was in Rhodesia in March this year, and thanks to that cameraman over there, I was lucky enough to meet you today.'

There were a lot of people standing around listening to our conversation.

'Thanks for your compliments,' Parveen said, 'but now I have to go inside the train to get ready for the shooting of the mahurat. I hope we'll meet again. Bye.'

'Bye, Parveen. I have to go back to Muscat now but I hope we'll meet when I return some day. Good luck.'

After she left, Zuber Khan pointed out different film personalities to me. 'This is Dharmendra, walking next to him is Hema Malini and over there, the lady with the ponytail, is Shabana Azmi. That young man is Ravi Chopra who is directing the movies. Burning Train is his directorial debut. He is B R Chopra's son. The young man walking behind is Vinod Khanna, a very popular movie star.'

The mahurat shot was being taken inside the train. I waited for some time outside the train, talking to someone from the production office of B R Chopra who told me to drop in and say hello whenever I was near their office. He gave me a business card.

***

'Subhash Ghai had to spend one day in the lock-up'

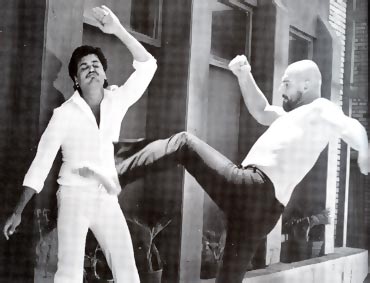

Image: The cover of Christo's FlashbackYet another close shave occurred off-screen. Sanjay (Khan, whom Bob Christo met on the sets of Abdullah, 1980) had a friend who owned the bungalow next to him. He also became an actor. He was quite popular. His name was Ranjeet; his friends called him Goli. One evening Sanjay, Goli and I were sitting together having drinks and snacks in Goli's place.

Other members of the film industry joined: Prem Chopra, Shatrugan Sinha, Subhash Ghai and some others. Somehow an argument started; after a few drinks moods often change and tempers rise. I am not interested in fights really; as long as I'm not involved, I keep out of the way. However, Sanjay was my friend and whatever Shatru said did not go down well with Sanjay. Since it appeared like the majority of those present were supporting Shatru, I stood up and stayed near Sanjay. That was immediately looked upon as a threat by the others. One person went into the kitchen and came out with a knife in his hands. I disarmed him and told them to control themselves. Several minutes later Sanjay and I left.

That very night I received a call from Sanjay at about 5 am. Sanjay said, 'Come over and bring Betsy,' which was our code word for 'gun'. I went right away and Sanjay explained that shots had been fired from Goli's property across to his bungalow and someone had also fired at least two shots from outside Sanjay's front gate.

The watchman had been slapped by somebody, but he hadn't seen who it was, since it was still dark. We picked up the spent cartridges of the bullets and handed them over to police after they arrive. After that we had some breakfast and later we visited Dilip Kumar to ask for his advice. Then I went to my place to take a shower and brush my teeth. Nargis had left a letter for me on the table.

It took a few days to sort everything out. Subhash Ghai had to spend one day in the lock-up until he was bailed out. The seniors of the Bombay film industry and Sanjay had a final meeting and that was the end of it. But from that time on Shatrughan Sinha was called Shotgun Sinha, although it also had something to do with his fast dialogue delivery.

'Sanjay Khan had suffered 65 per cent third-degree burns'

Image: From left: Bob Christo's wife Nargis, son Darius and son Sunil and daughter-in-law MonaI had stopped the night before at the studio, coming from a shoot in Ooty for a Tamil film with Rajinikanth, but I had carried on to Bangalore where I had to shoot the coming day for a Kannada movie. The date was 9 February 1989.

In the morning I read a little news item in the morning paper. It mentioned that there had been a fire during the shooting of Sanjay Khan's TV serial The Sword if Tipu Sultan but nothing serious had happened. Just to be sure, I rang Sanjay's Bombay phone number. One of the daughters picked up the phone and urged me to go to a particular nursing home in Bangalore. 'He will be there. And Mummy is on the way to the airport.'

I called up the nursing home and asked to speak to Sanjay Khan. After a while his brother Ahmed, also called Sameer, came on the line and told me to come to the hospital. I asked him to give the phone to Sanjay, but again Ahmed just asked me to come to the hospital.

So I went. Ahmed showed me where to go. I went into the room which Ahmed had pointed out to me but had difficulty recognizing Sanjay. His head was bigger than normal and his hair was burned down to a length of about half an inch. His hands and feet were raw flesh and the rest of the body was covered with cloth. The face was not so bad; he must have covered it with his hands when he went through the flames. I spoke to a few doctors; most were afraid that his chances of survival were only about 10 per cent. Sanjay had suffered 65 per cent third-degree burns, and even 20 per cent third-degree burns on your body can be life-threatening. Age was also an important factor, they said. Sanjay was at that time forty eight. He was not unconscious; he was talking to me.

I asked the doctors if they could transfer him to a specialized hospital for burn injuries. They got an ambulance ready and sent him to St John's Hospital, which had a burn ward. I accompanied him. I spoke to Sanjay on the way; he asked me how long by my estimate he would have to stay in hospital. I said at least thirty days and wished him best of luck.

'Sanjay went through a total of a hundred blood transfusions, donated mainly by college students'

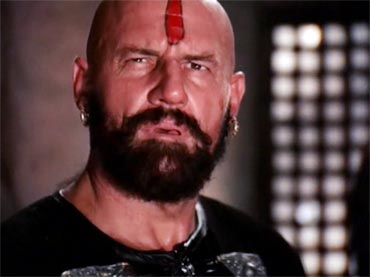

Image: Bob Christo in AjoobaThen I went to the airport and made my way to Bombay. Zarine had also arrived by then and was already entering Sanjay's room in St John's hospital. She was calm and controlled and spoke to her husband in a reassuring voice.

Sanjay's doctor from Bombay and the relatives got together and worked out a comprehensive plan for Sanjay's treatment. In the evening of that same day, Sanjay, his family and doctors boarded the J-class of an Indian Airlines Airbus. The plane had a special bed for Sanjay with a hook-up drip to prevent dehydration. Two nurses were also with him. From Bombay airport he was transferred to an ambulance and ferried to Jaslok Hospital, where seven years earlier my son Darius had been born.

For the next three months Sanjay was on the ninth floor of the hospital. He went through a total of a hundred blood transfusions, donated mainly by college students, and auto-donor skin transplantations were performed at regular intervals.

As soon as the donor skin has grown firmly to the surface of the body, it could be removed again and transplanted to a different area. Work was also done on his hands and feet. The last of the donor skin transplantations was performed on his back. For that he had to rest on the front side of his body for thirty days. Before that he was allowed to leave the hospital for about two week.

Comment

article