| « Back to article | Print this article |

This trio is truly one of a kind

Vijaya Mulay recalls her encounters with the amazing trio: Ismail Merchant, James Ivory and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala.

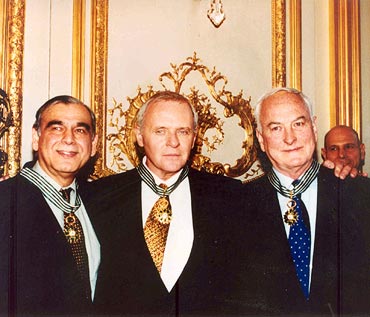

I encountered a problem in writing about James Francis Ivory (b 1928). However hard I tried, I found it impossible to isolate him and his work from that of his other two partners, Ismail Merchant (1930-2005) and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (b 1927).

Madhu Jain, a well-known Indian journalist, has described this unique partnership aptly: 'There has never been a menage a trois like this one: A marriage of minds, hearts (well, almost) and vocations. The triumvirate of Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala has gone into the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest collaboration in film history... But it is not the number of years or films; nor even the books written on them or the accruing legends of this 'Wandering Company' as it has often been described which lends them their uniqueness, and singular place in independent filmmaking.

Rather, it is this very independence, the resilience and boundless optimism not to succumb to the Hollywood school of filmmaking, which give their films staying power and a Merchant-Ivory stamp of quality.'

This special chemistry between an American, a European and an Indian, each with different talents and skills, needs to be explained to some extent. Any one of them could not have achieved what they have together.

Both Ivory and Jhabvala, highly talented, have impeccable taste in their special fields but without Merchant's unique entrepreneurial skills and energy, one wonders how far they would have progressed in the rough-and-tumble of commerce that is so very much a part of filmmaking.

Once Merchant was convinced a project was worth undertaking, he was unstoppable. Their firm had to remain independent because of the kind of films they wanted to make and therefore could not follow the ethics and methods of Hollywood studios. It also meant that their budgets had to be much more modest than Hollywood productions, without losing the quality and elegance that has marked their work.

Walking a financial tightrope is something at which Merchant excelled. He had immense charm, the ability to think on his feet and to sell dreams. He was also loyal to those who worked with him and provided openings for their maiden ventures. He managed to find money, locations, castles, costly artifacts, highly talented technicians and actors at comparatively modest cost.

In his My Passage from India, Merchant admitted that he paid his actors a pittance -- no actor would ever get rich acting in a Merchant Ivory Production. But still they came -- for the dream that Merchant unfolded for them.

Behind the charming exterior and energy lay the hard core of a focused achiever. Only Merchant could have got an actor (Editor's note: Utpal Dutt, the legendary actor) released on loan from a Bengal prison to act in their film Guru (1969). Jeanne Moreau, who acted in their film Proprietor (1996), told me in an interview that Merchant could charm anybody, including the French traffic police he got them to stop traffic near the Louvre while a particular sequence was being shot!

His contribution to the creative process of Ivory's films has also been considerable. For instance, despite the misgivings of Jhabvala and Ivory, merchant insisted on casting James Mason as Cyril Sahib in their TV film Autobiography of a Princess (1975) -- and it proved to be the perfect choice.

Again, in The Householder (1963), the reference to Nimmi and the inclusion of a clip from one of her Hindi films was his contribution. He had adored Nimmi in his teens and the Nimmi sequence works beautifully, and shows how the hero of the film still has the mindset of a teenager.

Excerpted from From Rajas and Yogis to Gandhi and Beyond, by Vijaya Mulay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.

From Venice to India

A proper understanding of Ivory's vision of India would remain incomplete without a study of how he came to filmmaking and how this partnership contributed to that vision.

When I interviewed him in 2002, in Delhi, he told me that Indian art and (Satyajit) Ray's films had formed his initial vision of India; later, it was shaped by his lived experiences in the country and by what he leant from Merchant and Jhabvala. When I told him that I considered people like him insider-outsiders, he thought it was an appropriate way to describe him:

I am certainly an insider-outsider. I learnt serious filmmaking here; I have made five feature films and two TV films on Indian themes. If you calculate about one and a half years for each film, it means that I have spent about a quarter of my mature life here. Then my partner is Ismail. We have always worked together and Ruth contributes in a big way to my scripts. All these are important elements for making me an insider. But I am not an Indian. I am now making films in my country and in France.

He considers Jhabvala's understanding of India to be deeper than his as she has been part of an Indian family. Therefore, he has allowed himself to be guided by her to a great extent. If one views his films chronologically, one can see that, as Jhabvala's way of looking at India changed, so did the portrayal of India in his films.

I first met Ivory in 1960 when he was making his second Indian documentary, Delhi Ways (1964). He had come to my house with a film society friend, and I was impressed by his knowledge of and enthusiasm for Delhi's architectural heritage.

In the summer of 1950, he went to Paris, to study filmmaking. But the start of the Korean War, in which the US was deeply involved, meant he would be drafted into the US army unless he was in a US college. So he returned home, and joined the graduate program in filmmaking at the University of Southern California. He combined his love for films and fine arts in the 28-minute Venice: Theme and Variations, inspired by his visit to Venice in 1950.

Venice led him to study eighteenth-century art and, eventually, to India. While researching for the film, he chanced to visit the gallery of Raymond Lewis, a San Francisco print dealer. There, spread out on a table, he saw a number of Indian miniature paintings that immediately aroused his interest. He then knew very little about India or its arts but he recognised the fact that the miniatures would look fabulous on celluloid.

He read everything he could find on Indian history and art and began searching for Indian miniatures on the West and East Coast, in museums and private collections in the US. This resulted in his first film on Indian paintings, The Sword and the Flute. This 20-minute film, completed in 1959, was justly acclaimed when it was shown in New York.

At our first meeting, he told me that the local office of the United States Information Service was to show this particular film. Ivory traces the history of Indian miniature painting as it developed into two major schools, the Mughal and the Rajput. The Mughal miniatures reflect an interest in historical events and the life of the Mughal courts; the Rajput school emphasises other worldly concerns and the yearning for transcendence. Though the two schools are distinct, they immediately involve the viewer in a world that is exotic and ravishing.

Excerpted from From Rajas and Yogis to Gandhi and Beyond, by Vijaya Mulay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.

Birth of Merchant Ivory

For Ivory, the film was a sort of dream -- it was India as imagined by someone who has never been there and who has only encountered it though its art and music.

Ivory's interest in India happened at a propitious time for the West was becoming more receptive to other cultures. Western audiences, for example, were enchanted by the music of maestros such as Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan and Ivory used the music of both in The Sword and the Flute. This was also the time when India had started registering more prominently on the radar of Western geopolitical strategists and economists.

It was in this climate that Paul Sherbert, who then headed the Asia Society, screened Ivory's films on Venice and Indian miniature paintings in New York. He then asked Ivory whether he would like to go to India and make a film on Delhi. Ivory was delighted. Sherbert got Mrs John D Rockefeller III, a patron of the Asia Society, to provide a sum of US $20,000 for two documentaries by Ivory: one about Delhi and the other in Afghanistan.

He shot a great deal in Delhi as well as collected archival footage and the result, Delhi Ways, looks at the city's different moods. He was able to complete it, however, only after his first feature The Householder was finished in 1963. Partly because his funds were exhausted and he had to return to the US. By that time, though, he had fallen in love with India and wanted to come back.

At a screening of The Sword and the Flute at India House in New York, he met Ismail Merchant, an Indian who had come to the US with the dream of becoming a film producer. Merchant was short on finances but his other assets were formidable. With a small budget of US $9,000, advanced by Charles Schwep of Trident Film, a distributing concern, he was able to make his first short film, Creation of Woman (1960), based on an Indian myth. It was 14 minutes long, mostly mine and dance.

He managed, against all odds to have it shown in competition at Cannes. He even managed to get it distributed by a Hollywood theatre chain along with their main picture. After such good beginnings, Merchant pursued with greater vigor his dream of making films about India for foreign audiences. He felt that there was a good deal of rich material that had never been properly explored by filmmakers and he was the person to do it.

On the recommendation of his friends Saeed and Madhur Jaffrey, Merchant went to see The Sword and the Flute, for which Saeed had spoken the commentary. The Jaffreys told Merchant that Ivory was an unusual American. After the screening was over, Merchant invited Ivory for a cup of coffee. He was interested to find out more about this American who had an empathy with the culture of India which was neither a dry academic interest nor a passing whim. The interest was born out of Ivory's artistic sensibilities that saw the close relationship between a people and their arts and culture.

Merchant found Ivory's script intelligent and the music of the two maestros made it for him a 'compelling film'. The quiet American and the energetic Indian found that their tastes in films (particularly for those of Ray, whom Ivory had met when he was in India) were similar and that they could work together to pursue their common goal. Thus was born the idea of 'Merchant Ivory Productions' and its birth formally legalised first in India and then later in the US.

Excerpted from From Rajas and Yogis to Gandhi and Beyond, by Vijaya Mulay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.

Bollywood's glam couple

Merchant was toying with the idea of making an autobiographical film about a young Indian coming to the US to produce films on India. He asked Isobel Lennart, a highly regarded scriptwriter at MGM, to write a script for it. She told him about a novel that she thought was absolutely appropriate for filming -- Hollywood would never make it into a film but he should. The novel was The Householder by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Merchant read the book and liked it; so did Ivory.

Jhabvala, who had met and married Cyrus Jhabvala while living in England, now lived in Delhi with him. She was not very enthusiastic about it but both Ivory and Merchant finally convinced her, and Ivory even persuaded her to write the script. She was hesitant, as she had never written a film script. Merchant's reply, quite typical of him, was that it was wonderful, for he had never produced a feature and Ivory had never directed one. She agreed and produced a script within 12 days.

Both director and producer depended a lot on the guidance of Ray, whom they greatly respected; and Ray helped them in every way he could. Ivory asked Ray to persuade his crew to work with them on their first film. Thus Subrata Mitra, Ray's celebrated cameraman, came with an entire team and masses of equipment. The sight made both Merchant and Ivory realise how far the reality of filming a narrative feature was from what they had theoretically discussed in New York.

Ivory's experience until then had been shooting his choice of footage for his documentaries and putting the material together as and when possible. Merchant describes the look of panic in Ivory's eyes hewn they went to meet the crew at the Delhi railway station and he saw the mountain of equipment that had come with them. Reality struck, and he suggested the whole thing be called off.

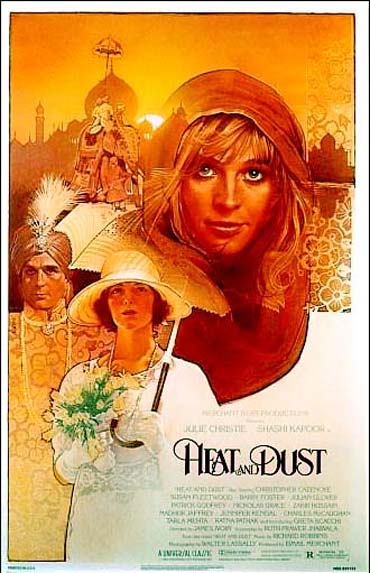

He was to the only one with such misgivings; Jhabvala too was assailed by doubts when she met the two protagonists of the film -- Shashi Kapoor and Leela Naidu.

In her novel, the hero was an ordinary schoolteacher. That role was now to be played by the very glamorous Shashi Kapoor and that of the ordinary housewife by the sophisticated and elegant Leela Naidu. She feared that her novel might become a glamorous Bollywood film.

Excerpted from From Rajas and Yogis to Gandhi and Beyond, by Vijaya Mulay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.

A touch of Ray

Ivory's filmmaking was honed to a fine art in India under the tutelage of Ray and his crew members. He studied Ray's style and gave much thought to Ray's approach to filmmaking; and it shows.

When I said this to Ivory, he said that it did not surprise him at all because the hand of Ray had always guided him:

When one starts working on feature films one enters an entirely different world. You work with other people; you think of your audience and wonder who is going to see them. It is an entirely different way of working. One has to be much more serious and mature. I think it is in India that I became a man. I matured as a professional and became a filmmaker. It might sound strange but it is the truth. India has influenced in many ways.

And in terms of filmmaking, Satyajit Ray has influenced me tremendously. I was enchanted by his films when I saw them in the USA but it was here that I learnt how he put them together.

He learnt from Ray's crew as well and paid them a tribute:

In my first few films, I used the same crew that worked with Ray. They knew how Satyajit worked. And they worked exactly in the same way on my films too. In a sense I was the pupil who learned the craft from the cameraman, the sound person, the editor, etc. Ray's people taught me the finer points of the craft; and the way I make films, the way I shoot, the things that I want to say through my films, the style of my filmmaking, are very much influenced by Ray's films. I have never analysed the filmmaking styles of Western directors. I mean I know what they do and see what they are doing but that has never seriously affected my work. But I thought a lot about Ray's films and his style. I met him as often as I could, and sought his advice. Ray re-edited The Householder. I learnt a lot just by observing his re-edit. He provided music for Shakespeare Wallah (1965). He also helped by giving many tips for other films as well; they all were very useful.

Excerpted from From Rajas and Yogis to Gandhi and Beyond, by Vijaya Mulay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.

Quintessential western

Their India films, right from The Householder, their first film, all have Western characters learning to live in India. This is natural, as both Jhabvala and Ivory are not Indians and their perceptions are bound to be those of non-Indians.

She (Jhabvala) came to India in 1951 as a young bride in a well-to-do family. In her interview with Robert Emmet Long, she said that the effect of India on her was 'stunning and overwhelming and beyond words'.

As she continued to live in Delhi, and saw her three daughters growing up, she too matured like the two main characters in The Householder. She started seeing the country in a different way, and a new consciousness dawned on her: 'She felt that she was no longer immersed in sensuous delights but had to struggle against all the things people do have to struggle against in India: the tide of poverty, disease, and squalor rising all around; the heat, the frayed nerves; the strange, alien, often inexplicable Indian character.'

In the second phase of her writing she pays more attention to how India affects foreigners. Ivory has made films from Jhabvala's scripts and novels from both her first and second periods, with The Householder and Shakespeare Wallah belonging to the first.

In 1975, Jhabvala moved to New York and spent her winters in India; her husband made frequent trips to New York. One could trace her second period of writing to around this time. Ivory's films Guru, Bombay Talkies (1970), and notably Heat and Dust are from Jhabvala's second period of writing.

I sometimes wonder why, despite speaking of it now and then, Ivory has not shot a film in India for 22 years. Perhaps he is aware, at least vaguely, that his vision of India does not quite match Jhabvala's.

When I asked him whether he found India much changed from the time when he first came here, he said, 'Outwardly it seems to have changed. Superficially it looks more Westernised, but I find that people talk and relate the same way as before. Modern communication and technology has brought about certain changes and there is the loss of secular life in politics.'

Excerpted from From Rajas and Yogis to Gandhi and Beyond, by Vijaya Mulay, Seagull Books, with the publisher's kind permission.