| « Back to article | Print this article |

'No photos did justice to Madhubala's beauty'

The name Madhubala conjures up so many images of the yesteryear actress in our minds. Her beauty, grace, comic timing -- everything about her has turned into a legend over the last 40 years.

Strangely, for a celebrity of her stature and repute there's hardly any documentation of the legendary actress' life and time.

That's what pushed Khatija Akbar to take up the task of writing a biography on Madhubala. In 'I Want To Live' The Story Of Madhubala the author has written about the lesser-known aspects of the actress' life.

Present here, are excerpts from the book:

Engraved on the collective consciousness of lovers of cinema the images remain fresh in every viewer's memory. She was perceived as the 'Venus of the Indian Screen' (Baburao Patel's appellation that stuck to her), but how was Madhubala viewed by those of her own generation in the film industry particularly the actress?

'She was ecstatically, exasperatingly beautiful', exclaimed Nadira in her characteristic style. 'She created a kind of reverence, she had such an aura about her.' Begum Para saw her sometimes in the mornings when she went out for a walk. 'You saw Madhubala's face and your day was made. She was a dream really '. Nirupa Roy recalled, 'She was perfect, right down to her toe-nails. There never was and never will be anyone with her looks'.

'Her complexion was so fair and translucent that when she ate a paan (betel leaf) you could almost see the red colour going down her throat', recollects Minu Mumtaz. Nimmi confessed to passing a sleepless night after her first meeting with Madhubala on the sets of their common starrer Amar. How would she fare in the film alongside 'this apparition, this angel in human shape?'

The feeling of being struck dumb was a normal first-time reaction to Madhubala whether the hapless one was Shammi Kapoor or a casual visitor on her sets. For his first picture with Madhubala, P N Arora's Rail Ka Dibba (1953), Shammi Kapoor, dialogue forgotten and his mind a blank, could only gaze tongue-tied and lost. His brother Shashi Kapoor regretted the fact that he never got to act with her:

'She had a porcelain beauty, like Dresden china, very fragile, very delicate with a gorgeous infectious smile and very expressive eyes. There was a mystery about her.' Producer-director Manmohan Desai remarked: 'She was the only true beauty to grace the Indian screen and she was beautiful in every film with no exceptions.' Well-known journalist B K Karanjia discovered on first meeting her that 'none of her published photographs did full justice to her quite extraordinary beauty.' Filmfare, the premier film magazine of the time, wrote:

Her complexion is moon-kissed and the smile an irresistible come-hither but stay-where-you-are smile. J H Thakker spoke from a photographer's viewpoint: 'You could photograph her from any angle without make-up and still come away with a masterpiece. She was a cameraman's delight.'

Excerpted from 'I Want To Live' The Story Of Madhubala by Khatija Akbar, Hay House, with the publisher's permission, Rs 399.

'She was made for laughter'

Madhubala and Meena Kumari were never cast together in any film, and in real life they rarely met each other; but they are often spoken of in the same breath, often compared. A sense of tragedy and doom hangs over the memory of both actresses, for, in their separate ways, they were powerless against the grim realities of their lives. Always under the control of others, their own sense of direction was inevitably overruled. An odd helplessness emanated from both, for they had no armour of guile and ruthlessness to battle the world. Easily hurt, they caused incalculable pain to their own selves.

Unhappiness had become a fact of both their lives, but Meena Kumari hugged her sorrows close to her heart, almost reveling in the sadness. A lonely woman, she drenched herself in her poignant verses (she was well-read and a good poetess) and when the barbs of life became unbearable she reached for the bottle and lost herself in its miseries. On screen too she chose to become the symbol of suffering Indian womanhood voluntarily limiting the range of her histrionic capabilities. Her potential was far greater and there are instance of joyous performances in films like S M S Naidu's Azaad (1955) and S U Sunny's Kohinoor (1960) but the scores of sorrowful characters she opted to personify made her name a synonym for tragedy.

If Meena Kumari seemed made for grief, Madhubala was made for laughter. Melancholy was unnatural her. To her smiles came easily; the tears were thrust on her. She constantly reached out for happiness, had no truck with the bottle and faced the travails of her life with more inner strength. Perhaps the order and the discipline that she was used to made the difference. She lived with the knowledge of a mysterious medical problem, and in later years the specter of death was like her own shadow.

With Meena Kumari, Madhubala shared the horror of a disastrous marriage, and both returned to their own homes, but Meena did not additionally suffer the trauma of losing the only man she ever loved In fact, she never really fell in love with anyone. Her life was a futile quest for love and understanding, which she expected to find in the most unlikely quarters. She either did not or could not judge people. The number of those who rose to fame and wealth using Meena Kumari as a stepping stone must be legion.

'Madhubala was just twenty when she joined Mughal-e-Azam cast

Madhubala was just twenty, with a natural, buoyant ebullience, when she joined the cast of Mughal-e-Azam. Her attitude was initially casual and she had no clear idea of how to approach her role. There was laughter and light-heartedness as she came on the sets. Shooting would begin, then, suddenly, Asif would order a pack-up. He let this go on for five days, recalled Sultan Ahmed (who was then Asif's assistant director), before he explained to his perplexed heroine that the role demanded a great deal more seriousness and that her mood should be appropriately subdued. On the sixth day when she came on the sets in her make-up and costume, there was a marked change. 'Ah', exclaimed Asif, with a satisfied puff at his cigar, 'now, you are my Anarkali'. And the shot was okayed.

Once she understood what was expected of her and what the demands of the role were, Madhubala rose to the challenge. She empathized increasingly with the character, breathed life into her portrayal and slowly grew into the role, imparting to it shades of her own personality.

Mughal-e-Azam gave her the opportunity of fulfilling herself totally as an actress, for it was a role that all actresses dream of playing. Regretting her own lost chance of working to the end of Love and God with K Asif, Nimmi remarks wistfully: 'As an actress one gets a lot of roles, there is no shortage of them, but there isn't always a good scope for acting. With Mughal-e-Azam, Madhubala showed the world just what she could do. All the signs of a good artist were there as far back as Basant, but Mughal-e-Azam was the final proof that she was an artiste par supreme.'

The set-up of the film was ideal. With the talent of each artiste being given full play, there was no question of one being allowed to overshadow another. No film had offered her such intense creative satisfaction nor inspired her to such heights. And as an actress, she had consistently been under-rated. 'Her beauty has justly been praised but her talent was far superior and its potential was never fully exploited.' Mughal-e-Azam was one film to which Devika Rani's perfectly justified accusation did not apply.

As already mentioned, a number of Anarkalis had already been seen on the screen; the character was not new to the public. The memory of Bina Rai with the haunting Yeh zindagi usi ki hai was still fresh in the public mind, and it was a challenge to take on this well-known, well-loved character and make it successful once again. All doubts were put to rest when Madhubala's Anarkali emerged on the screen pulsatingly alive, vibrant and three-dimensional.

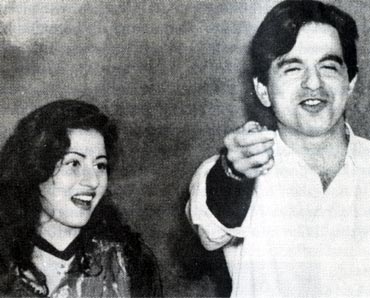

'She couldn't overcome her break-up with Dilip Kumar

Dilip Kumar and Madhubala were both very private persons, and their meetings were away from the public eye. 'They went out for drives after shooting', said a friend, 'or she picked him up on her way to the studios. She'd sound the horn and he came out and joined her. She did not enter his house. It looked very much like they'd get married any day. When Dilip Kumar married Saira Banu [in October 1966] she did not like it.'

The perceptive Nadira saw it too: 'She considered herself married to him. They were almost married. She wore his ring, he wore hers.' Dilip Kumar himself acknowledged it in a statement to a newspaper, saying a proposal had been sent from him. A film journalist of the time, Ram Aurangabadkar, reported that Dilip Kumar sent his eldest sister, Badi appa, to Madhubala's house with a marriage proposal, saying they'd like it to be in seven days. Ataullah Khan refused.

As love stories go, Dilip Kumar and Madhubala's had one essential difference. There were no obstacles to speak of, and the usual encumbrances and thorns in 'the path of true love' were hard to find. Both were Pathan Muslims, both at the peak of their careers, their ages were compatible and, most important each was single and uncommitted. Ostensibly, there was nothing to stop them from getting married if they so wished. Yet the two became alienated with a completeness that was unambiguous.

The scenario was bizarre. With feelings for each other just as strong, with no other individuals creeping into either of their lives, they persisted in proceeding to destroy their relationship almost as if compelled by forces beyond them. In the space of about five to six years, the near-perfect romance had succumbed to the dictates of its destiny. While Dilip Kumar appeared to emerge relatively unscathed, for Madhubala, it was the beginning of the end; the festering wounds she carried never really healed.

Emotional to a fault, guileless in the bargain, she was simply not equipped to deal with the shock of the break-up. Speaking of her, Nadira once remarked: 'She had not a strain of pettiness, of anything small. That girl did not know anything about hate. She was in love with love. Exuberantly, overflowing with love. She had so much to give.'

'Madhubala and Kishore Kumar were a highly ill-suited couple'

In choosing to become Mrs Kishore Kumar, Madhubala had taken the most irrational decision of her life. The general reaction to her marriage to Kishore Kumar was echoed in Nadira's incredulous disbelief: 'From the sublime to the ridiculous! Oh my God! Madhu what are you doing? All her father's efforts to precisely monitor her life were coming to naught as her destiny continued its dance of destruction. Skirting Dilip Kumar, Premnath, Shammi Kapoor, or perhaps even Bharat Bhushan, with any of whom she may have found her happiness, it deposited her into a loveless marriage of sheer incompatibility.

Appearances were not deceptive in this case for, if Kishore and Madhubala seemed an unlikely pair, that is exactly what they were: A highly ill-suited couple who had married in haste and never found any happiness together. Kishore was to discover his ideal wife much later in Leena Chandavarkar, but for Madhubala it was the end of the road and there were no more chances. She had sought to escape her painful memories but succeeded only in inviting further disaster upon herself. Once again, she had taken a wrong decision. Once more, she paid for it.

The marriage was a disaster and Madhubala's most difficult years had begun. A time came when the Venus of the Indian screen could find no one who was willing to go with her when she wished to consult doctors abroad. An old acquaintance was so moved by her plight that she offered to accompany her; Kishore then relented and went himself.

They went to London in 1960 but the doctors who saw her both in India and abroad merely asked her to avoid any kind of stress, strain and anxiety, and to learn the art of relaxation. She was advised against having any children. In short, no hope of any cure was held out. She was told she could live for ten years or die within the year. Surgery for a hole in the heart, which became common shortly after Madhubala died, had not been heard of in the sixties.