| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why Leela Naidu never lost her cool

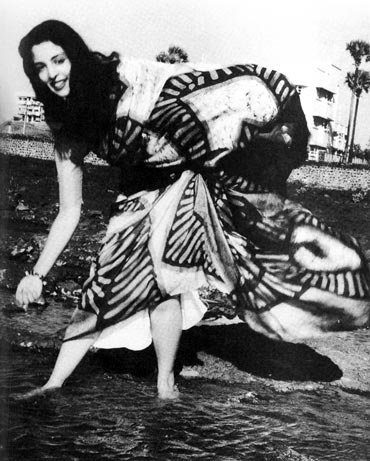

Leela Naidu's beauty is legendary.

But she was not just another pretty face. After all, how many actresses do you think would turn down an opportunity to work with Raj Kapoor?

She left an impact on many who met her. Ashok Kumar, who would forget which character he was playing, remembered Leela Naidu.

In this second part of this excerpt from Leela: A Patchwork Life, the late actor shared her amazing story.

It was a delight to work with Ashok Kumar. He was a great actor, but also one of a peculiar breed that could belong only to Hindi commercial cinema.

Ashok Kumar would come on to the set and look around. He would greet everyone and seemed to be very much at home. Then he would come up to me with a wry smile and say, 'Leela, tell me, what is the name of the film?'

I would dutifully tell him the name of the film.

'And what is the name of my character?' I would tell him that too. 'And yours?'

Excerpted with the publisher's permission from Leela: A Patchwork Life by Jerry Pinto published by Penguin Books India.

'Dada Moni could be great fun too'

He was generally on the second of the three shifts of his work day. Anyone who works on several films at a time is likely to get confused.

'Will you get them to write my character's name on the tripod of the camera?' he would ask and then vanish into his green room to get ready.

If I found that a little tiring the tenth time, I did not show it. There is no point losing your cool in a collaborative enterprise like cinema. Everyone has their idea of preparation and everyone has their idea of what constitutes a career. I had mine and Dada Moni had his.

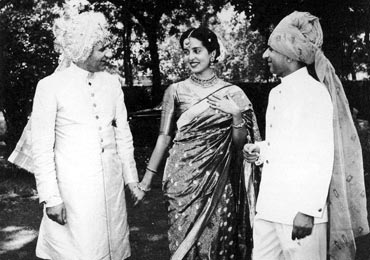

However, he could be great fun too. In Ummeed, an unreleased film directed by Nitin Bose, I played his daughter.

In one scene, he was supposed to be dying and I was supposed to approach his bed to take his blessings. The foot of the bed had been placed on a whole pile of bricks in order to raise it. This had something to do with the lighting.

Dada Moni, the prankster!

Take one. I approach the bed, hopefully with the gait and bearing of a woman about to lose her beloved father. I lean over him and a maniacal cackle erupts from Dada Moni.

Everyone, including me, jumped a foot. Dada Moni pulls out a laughing box, the kind of gadget young children enjoy and shows it to me. Obviously, the take was declared NG, or No Good. Many apologies and we begin again.

Take two. I approach the bed, etc. etc. It seems that my screen father was unwilling to die for another hysterical cackle erupted.

The odd thing was that he managed to startle us all again. This seemed so gloriously funny to Dada that he began to laugh in earnest. He laughed and he laughed and suddenly the bricks were shaking and the bed was tottering and down they all went in a heap.

When everything was raised again, he died quite perfectly and with no retakes needed.

'Oh please Mr Rehman, please finish this stupid line and let us all get on with our lives'

That was not always the case with other actors.

In Yeh Raste Hain Pyar Ke, we had to shoot what was, on the face of it, a perfectly simple scene. Rehman was supposed to knock on the door. I open it. He has to say something like, 'I dropped by to give your children these chocolates.'

Nothing more than that. No histrionics. No emotional complexities, No difficult blocking. No long speech. A single line. If anything, it was a scene that required me to get through a sequence of events. I am lying down. I hear the knock. I respond. I get up. I hush my disturbed children. I go to the door and open it, all in one shot.

And yet, it is part of the mystery of acting that this veteran of hundreds of films would simply dry up after he'd managed the 'good evening'.

We used up thousands of feet of film as Rehman would start with his 'good evening' and then fall into an abyss of silence.

By the twentieth take, as I rose once again, to hush my children and walk to the door, I was pleading with him in a little part of my head, 'Oh please Mr Rehman, please finish this stupid line and let us all get on with our lives.'

But it went on and on and my face muscles ached as I kept trying to respond with the right mixture of surprise and suspicion that any woman might feel at a late night caller.

Finally, someone suggested that Rehman be taken away and given a snifter. This was duly done and he came back, slightly flushed of face, and gave a perfect take.

'I'm not using glycerine. I'm crying'

But when we were shooting Arzoo, even the snifters had ceased to work.

This was a film in which I preside over much of the action from behind glass and a garland.

As the first wife of Rehman, I was preparing to die, as the script required me to, early in the film. Rehman muffed the first take but pretended he was doing it on purpose.

I gulped back my tears, dried my face, and got back into position. He muffed the second take but said that he was practicing. I asked him, 'Could you let me know when you are ready? Because I'm not using glycerine. I'm crying.'

He assured me that he was ready. So I mopped up again and affected some repairs to my make-up and got ready to die.

The tears rolled, the cameras rolled but Rehman came to a standstill. It took him fourteen takes and left my eyelids feeling like sandpaper.