| « Back to article | Print this article |

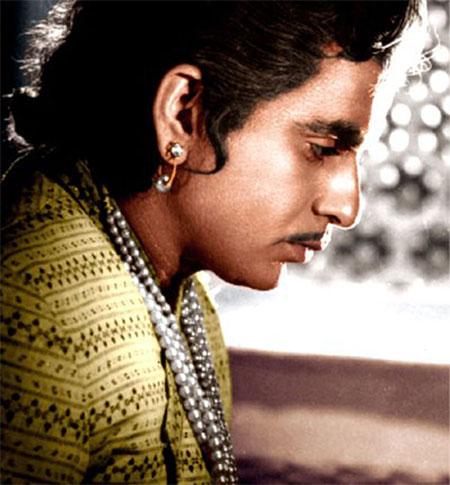

Dilip Kumar: The Gentleman Hero

As thespian Dilip Kumar turns 90 on December 11, Malavika Sangghvi looks back at the life and times of the great actor and nationalist.

In the early '80s , my mother and I were holidaying in Goa when we happened to run into Dilip Kumar and Saira Banu who were staying at an adjacent hotel.

He had been an old friend of my father's, but still, beyond the warm Pathan embrace and social niceties we did not expect anything more from the encounter. After all, stars inhabit different constellations and couples need their privacy.

And yet, for the rest of our stay Saira would call and invite us to dine with the couple in their cottage. And each evening, in exquisite English, Hindi and Urdu, the legend would regale us with stories dredged from the great canyon of his life.

One story was particularly gruesome. The actor told us of a village of his youth which had been tormented by a serial killer. The man had finally been caught and, as retribution, tied to a tree and stoned to death.

But while dying he admitted why he had killed. "It was the sound of the blood gurgling out of his victims' throats that he had become addicted to — the 'gggrrr'..." Dilip Kumar said, mimicking the burbling vividly.

I couldn't sleep for weeks after that.

'Satyajit Ray described him as the ultimate method actor despite never working with him'

As acting legends go, Dilip Kumar's was a modest one.

Born Muhammad Yousuf Khan, the son of a Pathan fruit merchant with orchards in Peshawar and Deolali, he was "discovered" by Devika Rani while he was running an army canteen in Pune and launched in Jwar Bhata in 1944.

"He hit the big league with his fourth film, Jugnu (1947), where he played the lead opposite the legendary singing-star Noorjehan," says senior film journalist Rauf Ahmed who has edited Filmfare and Screen.

"It was followed by four more blockbusters: Nadiya Ke Paar (1948), Shaheed (1948), Shabnam (1949) and Andaz (1949)."

"Satyajit Ray described him as the ultimate method actor despite never working with him," says Jitesh Pillai, editor of Filmfare.

"He holds the record for winning three consecutive Filmfare best actor awards -- in 1955, 1956 and 1957, for Azaad, Devdas and Naya Daur, respectively."

"For me he is and will remain the greatest actor of Hindi cinema for many decades yet," says economist Meghnad Desai who wrote a book on Dilip Kumar, Nehru's Hero: Dilip Kumar In the Life of India.

"His 1950s performances are his best. He debuted in the 1940s and by the 50s, he had matured a lot. For me, Devdas is his best role ever, because he internalised the character's trauma and alcoholism, but never romanticised it," says Sidharth Bhatia, the author of Cinema Modern: The Navketan Story.

"He bought me a banjo for my seventh birthday and used to come over after his shooting to teach me how to play it," says Pinky Bhalla, daughter of acting legend Pran who was a neighbour and close friend of the actor's.

'I'm Dilip Kumar and I do a bit of work as an actor'

Every nation needs a hero and in the post-Partition, nation-building fervour of the '50s, Dilip Kumar was India's.

A handsome Muslim who quoted Ghalib, threw himself into nationalist campaigns, was fond of the company of Left intellectuals, and reprised dark, tormented characters to perfection on screen -- who wouldn't fall in love with him?

Business consultant and philanthropist Bakul Patel, wife of the late barrister Rajni Patel who has been tying rakhi on Dilip Kumar, talks of the enduring friendship between the men.

"They met during Krishna Menon's campaign for the North Bombay constituency in the Lok Sabha elections," she recalls.

"Rajni walked into the electoral office and a man stood up. 'I'm Rajni Patel and I do a bit of work as a lawyer," he said. 'I'm Dilip Kumar and I do a bit of work as an actor,' said the superstar."

The friendship endured till Patel breathed his last and involved many evenings at each other's homes in the company of others such as the architect I M Kadri and artist M F Hussain.

A man is known by the company he keeps. But, perhaps, it says more about the times we live in that whereas Dilip Kumar sought out the company of lawyers, writers and artists, Amitabh Bachchan, post his Gandhi phase, befriended Amar Singh and Anil Ambani.

Shahrukh Khan reportedly hangs out with Lucky Morani and Rajiv Shukla.

When Dilip Kumar almost got arrested as a Pakistani spy

Vir Sanghvi, advisor, HT media (and my former husband), whose father, the late Ramesh Sanghvi, was also part of Kumar's circle, says, "My first childhood memory pertains to the release of Ganga Jamuna, which the censors were reluctant to pass in its original form and demanded scores of cuts.

After trying to explain why the scenes they wanted deleted were integral to the movie, Dilip Kumar gave up and approached my father who was a lawyer.

And so, it came to pass that after school each evening, I would end up at a preview theatre where my father, Dilip and a few others were watching the film for the umpteenth time. By the end, I knew every piece of dialogue!" he says.

Vir's second memory of Dilip Kumar's brush with the state is grimmer.

"I distinctly remember the look of shock on my father's face when Dilip Kumar dropped in to tell him that he was on the verge of being arrested as a Pakistani spy. In those days, Dilip Kumar was India's 'great secularist', a film star who was feted for his nationalism.

"How could anyone possibly imagine that such a man was a spy?"

I too remember this episode. The whispered indignation and dismay at home, the flurry of letters sent to Jawaharlal Nehru to get the calumny removed. And the anguish on the handsome star's face.

"Bit by bit, the story emerged. It transpired that the police had arrested a young man on grounds that he was spying for Pakistan. In his address book, they found several names, including Dilip Kumar's. On the basis of this slender evidence, they decided that Dilip Kumar was also under suspicion and raided his house," recalls Vir.

'He was the first to sign up for every cause and campaign -- be it flood or drought relief'

But heroically, even though his patriotism had been questioned, Dilip Kumar's steadfastness to nationalist ideals did not falter.

"He was the first to sign up for every cause and campaign we mobilised -- be it flood or drought relief -- and also to enlist the support of all his film colleagues," recalls Bakul.

Unfortunately, the cloud of slander hovered for a long time, settling once again when Shiv Sena's Bal Thakeray demanded that he return an award.

"I met him in August 1997 when there was a lot of agitation against him over the Nishan-e-Imtiaz award from Pakistan," says Meghnad Desai.

"He was very friendly, a delightful raconteur and willing to devote all his time to us. But as it happened, he did not feel up to collaborating, so I wrote the book as a desktop study about how his films during Nehru's life time (films which I had seen at their first showing) reflected India's changing politics."

In another anecdote, Desai demonstrates Dilip Kumar's non-materialistic qualities that so endeared him to his Leftist friends.

"Once when we went to see him, Sairaji was there and he came later. She told us about how he was being offered a large sum of money, around Rs 75 lakh, by a business group to do a prologue for the colour version of Mughal-e-Azam.

"He did not want to do it. The couple was obviously having an argument about it. When he came, he had forgotten who I was and thought we were the business people set up by Saira for the request. He told us he did not care for money.

"That relationships mattered far more. After about 45 minutes of this I realised what had happened. So I reminded him who we were and then he became friendly again."

It would be prudent to remember that while both his contemporaries Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand went on to establish flourishing production houses and studios, Dilip Kumar restricted himself to acting.

'His performance in Shakti had Raj Kapoor telling him, 'There is only one Dilip Kumar'

It is difficult to do justice to the trajectory of Kumar's career or sum up his body of work in a newspaper article.

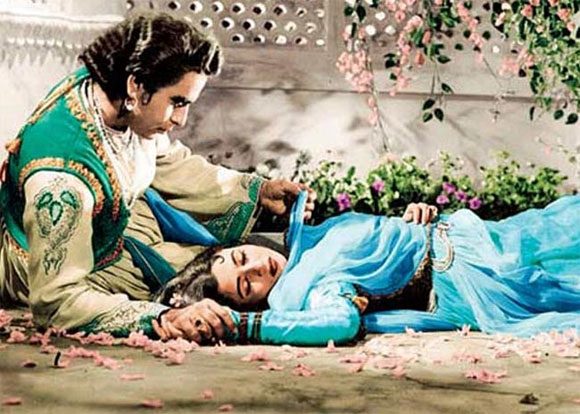

Where does one begin; what does one leave out? His brilliant rendition of the dialect of the Uttar Pradesh hinterland in Ganga Jamuna; his comic and flamboyant streak in films like Aan, Azaad and Kohinoor, the subtlety and the way he used his body to convey the flawed Devdas, his performance in the lesser-known Shikast and Footpath; his role in Mehboob Khan's Amar, his range in roles like Ram Aur Shyam, Naya Daur, Madhumati and Leader.

"If you were to break up his career into segments, they would be roughly tragic and flawed heroes (mainly 1950s), light-hearted romantic films (mainly '60s and a bit of '70s, on the insistence of a Harley street psychiatrist who he had consulted for his depression) and character actor -- '80s and beyond," says Bhatia.

"When his career as a hero ground to a halt in the mid-'70s, in the wake of the failure of films like Daastan and Bairaag, the obvious assumption was that he was out of tune with the times in an era dominated by a new breed of actors led by Amitabh Bachchan.

"But he came back with a vengeance six years later in 1981 with producer-director-actor Manoj Kumar's Kranti," says Ahmed.

"In the post-Kranti phase, Kumar reinvented himself to play the 'angry old man' effectively in a series of films, including blockbusters like Vidhaata, Karma and Saudagar.

"His virtuoso performance in Shakti had Raj Kapoor calling him in the middle of the night and telling him 'there is only one Dilip Kumar'," he adds.

Dilip Kumar's head-on encounter with Bal Thackeray

But heroism is not necessarily limited to the big screen.

In the '80s, about to enter a splashy politician's wedding on Mumbai's Chowpatty beach in the queue ahead of me, I saw Dilip Kumar in a head-on, face-to-face encounter with Thackeray who had been a long-time baiter of the actor. "Kyon Dilip bhai," said the leader in his characteristic slightly insinuating, taunting way, "What can I say to you?" I saw Kumar draw himself up to his full Pathan stature: "What can you say?" said the great thespian with the subtest hint of wounded dignity.

"It's best you say nothing."

And then he turned away.

Real heroes write their own dialogues.