| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Balraj Sahni was a misfit in filmdom'

On his birth centenary on May 2013, veteran actor Balraj Sahni's grandniece, Malavika Sangghvi, recounts his extraordinary but sad life.

The world knew him as Balraj Sahni, the celebrated actor, humanitarian and litterateur. But for me, he was always Balrajji or Mamaji, my maternal grandmother's younger brother and hence my granduncle.

In many ways, he defined our family and gave the clan its moral fibre and its mythology, its deep unspeakable sadness and its great leaps of sunshine.

For me, in particular, a bookish child, preternaturally picking up on what occurred in the margins of adult behaviour, he was visible in the sudden sigh that would punctuate the belly-aching laughter of my mother and her sisters while remembering their childish pranks with him, the long sulks of other alpha male creative geniuses when Balrajji entered the room, the bottomless well of adoration he invoked in whoever he met -- coconut sellers on Juhu beach, members of his beloved Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA), his Christian neighbours, his Punjabi writer friends, his once well-heeled but now Partition-scattered family, for whom he was the pivot, the trailblazer, the great roof under which they would try to recover themselves. I noted it all.

For me, the story of Balraj Sahni will always be an edifying one that speaks of an extraordinary zest for life's highest values and of a free unfettered spirit.

"Bold initiative and an inventive, imaginative mind, characterised his boyhood years; these qualities were reflected as much in the games he played as his studies. There was always something unconventional about his choice of games," wrote his brother, the acclaimed writer Bhisham Sahni, in his book Balraj, My Brother.

"He would soon tire of a game, which he had played several times, and invent another. Later in life too it would not take him long to break away from a profession or a pattern of life and adopt another."

Perhaps this is the key to understand a man who made his brief life so vital and extraordinary that it appears to be the story of several people instead of one.

Here was a man born in 1913 into a prosperous business family in Bhera (now in Pakistan) who, having completed a double MA in literature, turned his back on his father's business to launch into the creative arts and nation building.

He first taught at Tagore's Shantiniketan, then lived and worked with his young wife Damayanti at Mahatama Gandhi's Sewagram ashram in Wardha, sailed to war-torn London to work in the Hindi wing of BBC where he developed a love for Russian cinema and befriended the likes of Harold Laski, TS Eliot and John Gielgud.

He then returned to India, an avowed Marxist, to become a leading member of the IPTA and, of course, one of the country's finest actors.

'Our family home in Srinagar would reverberate with his singing and laughter'

My childhood coincided with the 'childhood' of the film industry.

"Very early in my life, I had found myself drawn to films," wrote Balraj-ji in his autobiography, Balraj Sahni: An Autobiography.

But, like everything else in his extraordinary life, a career in films was not a pre-planned move -- it was serendipity and happenstance!

For the Sahni brothers, "their love for literature was overpowering," wrote his second wife, Santosh, a writer of short stories, whom Sahni married after Damayanti's death.

"Our family home in Srinagar would reverberate with his singing and laughter," recalls my mother, Usha, his eldest niece. "When he returned from Shantiniketan, he was given to singing Rabindra Sangeet at the top of his voice," she adds. "And from another floor would come his brother's answering couplet."

Sahni's tryst with Neo-Realistic cinema began in London. "A cinema hall on Tottenham Court Road had started showing Russian films," Balraj-ji wrote about those electrifying days. "It was, in fact, a Russian film which I happened to see in that picture-house that restored my confidence in films, indeed in life itself. I still recollect every detail of that memorable film. It was called The Circus. The film had a profound effect on my mind -- so much so that when I came out of the picture-house, I was in a world of my own, totally unmindful of the splinters of glass and stone flying about me, obviously the result of a bomb which had exploded in the neighbourhood!"

This kindled his interest in Russian cinema and art, which introduced him to Marxism and Leninism. "Marx's Das Kapital had a profound effect on me. It was as if I had found a solution to a major problem. I realised that acting is just one of the several vocations that men follow. Just as a carpenter or an engineer meets a specific physical requirement of his fellow citizens by supplying them with a table or a machine, a playwright or an actor satisfies their psychological urge through his play or his role. Both types of work are equally useful to society; there cannot be any 'gradation' between them," he wrote.

My mother remembers that the Sahnis had brought back from London cartons full of books and their heads full of this ideology that would alleviate the world's injustices.

'Evenings at Balrajji's home was cacophony of song, games, conversations and laughter'

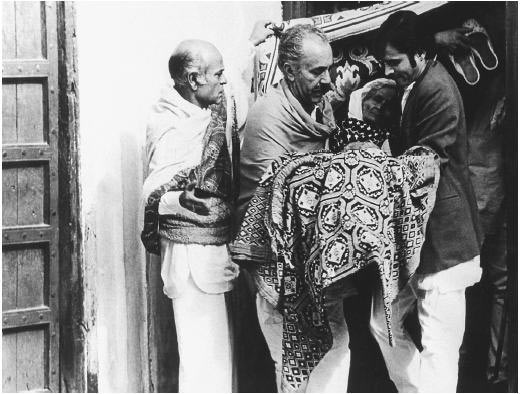

Do you remember that scene in Bimal Roy's masterful Do Bigha Zamin (1953) in which Balrajji, playing the skeletal, gaunt-faced farmer-turned-rickshaw-puller, almost kills himself to fulfill a whimsical woman's demand for speed?

Do you know how many times the young actor rehearsed that scene almost to the point of exhaustion?

Or that scene from Waqt (1965) in which he, as a proud Panjabi patriarch, sings of his earthy exuberant love for his wife (played by Achala Sachdev)?

That role was a reflection of Balraj-ji's own deep and abiding love for his family, for laughter and high spirits, and for exuberance and song that resounded at his home -- first the quaint thatched-roof cottage in Juhu's Theosophical Society and then Ikram, the palatial white bungalow further down which housed his wheelchair-bound, khadi-spinning mother (Mataji), his artistic but aloof wife, Santosh, his fun-loving and ebullient children (Parikshat, now the noted television and film actor, Shabnam and Sanobar, an alumnus of Tata Institute of Social Sciences whose work with prisoners has won acclaim) and for some time also my mother who he sheltered during a long spell of slipped disc.

Evenings at Balrajji's home were nothing if not a great cacophony of song, games, conversations and laughter. The poet Harindranth Chattopadhaya would recite his poems, there would be endless rounds of dumb charades between adults and children, Marxists would drink Vodka, and quarrel late into the night, the teenaged Shabnam would play her new Santana LPs, the young actors from next door, Feroz and Sanjay Khan, and their glamorous girl friends would drop-in, intellectuals like PC Joshi, lawyers like Rajni Patel and writers like Kaifi Azmi would hold forth about their latest activities.

Yet, there was yearning for something he had lost.

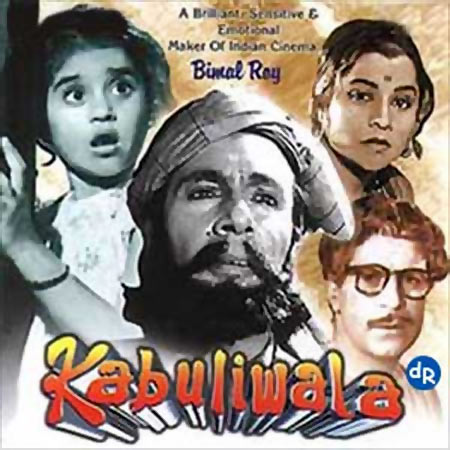

Remember that cherished scene from Kabuliwala (1961), in which Balrajji portrayed the yearning for his motherland with such palpable ardour? It arose from his own yearning for the land he'd loved and lost: his birthplace in Pakistan.

'Balrajji would be the first to initiate high-spirited pranks in the company of children'

And can you ever, if you've seen it even once, erase from your mind that heartbreaking scene from Garam Hawa (1973), the last that Balraj-ji shot in his life, in which he opens the bedroom door to his young daughter's suicide scene?

It came from the deep well of sadness in his life -- he had lost his beloved daughter, Shabnam, only a year before.

Could it be that the flawless and memorable roles he played on screen had been honed from the stalk and root of his own life? Is that why his performances achieved the resonance and universality that they are known for? Could it be that his art was so enriched because he had lived so close to life's marrow? Is that what makes art great, the ability to cull from it its most trenchant truths?

Still, Balrajji's life was far from sombre earnestness.

It was he who'd be the first to initiate high-spirited pranks in the company of children and who could be spotted early morning on Juhu beach performing flawless headstands. He made us kids gather around and listen to Simon and Garfunkel's Sounds of Silence in the late 1960s.

On one occasion when I had asked him what it meant that a somewhat pompous Marxist script-writer had been described as a 'committed writer', Balraj-ji replied with a twinkle in his eye: "Like a flea committed to bite a dog!"

It was he along with his brother Bhisham who, on losing their sister, had engulfed her young children in his embrace and given them succour and love. It was he whose house was always open to whoever needed shelter, it was he who at every flashpoint of communal disharmony would rush to the area, be it Bhiwandi or war-ravaged Bangladesh, and it was he who epitomised so effortlessly the words "generosity of spirit" and "selflessness".

And yet in this landscape of so much lightness and love was the tight knot of despair: the trauma of Partition, his disillusionment with Communism -- the God that failed -- and the tragedy of losing loved ones -- his older sister Vedvati, young wife Damayanti and then Shabnam. Ethereally beautiful women who didn't live to see 30!

My aunt, Kalpana Sahni (professor emeritus, JNU), the author of Balraj and Bhisham Sahni: Brothers in Political Theatre, vividly narrates an incident: an old gardener at the family home in Srinagar had chanced upon Balrajji, by then a celebrated actor, huddled one cold morning at the doorstep weeping his heart out.

When he'd arrived, and for what purpose, to his ancient and abandoned family home had been unclear. This longing for his roots began to gnaw at Balrajji's soul as he grew older and faced personal and private vicissitudes.

'Balrajji cut down film-work considerably, so that he might devote more time to writing'

For all his success, Balrajji was a misfit in filmdom.

His formative years were charged with idealism. He grew up in an Arya Samaj household, where his father talked intensely of the necessity for social reforms.

The subsequent years were filled with nationalist urges and the spirit of dedication. He had lived in close proximity to the two great idealists of our time, Gandhi and Tagore.

And subsequently, when he became a Marxist, his mind was again fired by a sense of commitment to the cause of suffering humanity.

"Such a person cannot easily reconcile himself to the sordid reality of a sphere where art is at a discount and money values prevail." wrote Bhisham. "To grow rich and famous as part of this machine gave little personal satisfaction or any sense of fulfillment."

"I am devoted only to literature," wrote Balrajji to his brother about his yearning to leave films and lead the life of a writer, adding, "and that also, most of all, to my Punjabi literature. Even if I am not able to do any original, creative writing in Punjabi, I can at least translate into Punjabi, and that way live a useful life..."

"Balraj-ji cut down film-work considerably, so that he might devote more time to writing," wrote Bhisham. "He even purchased a small cottage in Punjab, got it repaired and furnished so that he might go and live for longer periods of time in Punjab."

But that was not to be.

On 13 April 1973, a month before his 60th birthday and the day that he was to depart Mumbai finally to live in Punjab, Balrajji suffered a massive heart attack and died at the Nanavati Hospital in Mumbai.

"Apart from friends and relatives and some dignitaries, there was a motley crowd of fishermen, hotel bearers, the poor people of the locality and even street urchins. I was overwhelmed when I learnt that the fishermen had walked down from Versova on learning about his death and kept vigil by his body all night long, that the hotel-bearers were those who had been financially helped by Balraj during the days of their long strike against the management," wrote Bhisham.

A man at ease with princes and paupers, who aspired to life's highest values and ideals and who threw himself into its vortex with passion -- that was my granduncle, Balrajji!

(This article has used information from research by Deepti Naval for a forthcoming documentary on Balraj Sahni)