| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Dev Anand was too much in love with himself'

Arthur J Pais wonders why the evergreen legend did not make brilliant films even in his old age, like some of his peers in the West.

As I watched Max von Sydow play a mysterious immigrant and offer yet another mesmerising performance in film Extremely Loud And Incredibly Close, my mind went to Dev Anand.

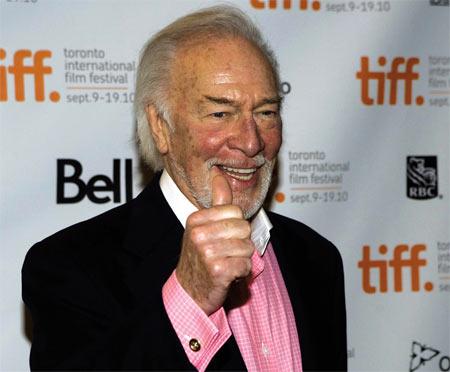

I have been thinking a lot about Dev Anand in recent weeks. Like when I saw Christopher Plummer roll out yet another solid performance in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo in a career that -- like von Sydow's -- has been going on for over six decades.

Von Sydow, best remembered for playing the devil chasing priest in The Exorcist, but whose best work is seen in many of the 11 films he did for Ingmar Bergman, is in his early 80s.

Plummer, popularly remembered as The Sound of Music actor, is about 82 -- not quite as old as Dev Anand was at the time of his death (88) but nevertheless.

In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Plummer walks into the viewers' souls as a rich and powerful man obsessed with the disappearance of a family member. The actor, who received his first Academy Award nomination in 2009 as a supporting actor for playing Leo Tolstoy in The Last Station, has four films out in the next three months.

He might have another nomination for Beginners, a small film compared to Dragon, as a father who comes out of the closet near the end of his life.

And on the subject of octogenarians whose creative juices are flowing steadily, there is P D James's latest novel, Death Comes to Pemberley. It draws some of the most beloved characters in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice into a web of conspiracies and murder.

James, who is a Conservative Party member of Britain's House of Lords, has been writing for over five decades and has produced more than 25 first rate mystery books including Death in Holy Orders, which also serve as fine morality tales. Many believe her latest is one of her five best novels.

Please click Next to read further...

'How many producers and directors well in their 80s make films year after year?'

And once again I think of Dev Anand, one of the busiest filmmakers in India who must have been plotting his next film when he died in London.

I admire him much for making enjoyable films like Tere Ghar Ke Saamne, Guide and Jewel Thief. Once upon a time, he was so creative and daring -- look at Hum Dono and Guide, which went against the grain.

But none of the nearly dozen films he produced and directed after nearly 30 years (including Censor, Love At Times Square and Solah Baras Ki) made any money, let alone win any acclaim.

And yet, Dev went on making one flop after flop because he could. His films cost little and his film lab brought him steady revenue.

Some people admired this, saying his energy was exemplary, and declared that his persistence was legendary. I wonder how many of them saw the films Dev Anand made in the last two-and-a-half decades.

When he was in New York to release his autobiography, I randomly asked over 30 hardcore admirers -- some of them had brought their grandchildren along, telling them they were going to see an evergreen star -- about the last Dev Anand film they had seen.

Not surprisingly, most of them had not seen a Dev Anand film either in a theatre or on television for over three decades. But they were cherishing films like Guide and Hum Dono.

I remember a journalist acquaintance in Mumbai who sees every Dev Anand film, saying that he saw the first show of the last Dev Anand film, Chargesheet. He was afraid there would not be a second show.

He was not too wrong. The film had a lame run in less than 60 theatres; in many houses, it didn't last even a week. The trade publications had only one word to describe its run: Disaster.

"But he is a world phenomenon," said one admirer. "How many producers and directors well in their 80s make films year after year?"

How about quality, I asked. What good is persistence and passion if the films were lousy? I got a dirty look and something the man uttered below his breath sounded like a curse.

About eight years ago, a colleague interviewed Dev Anand in New York. He asked the filmmaker and actor if he was worried about so many of his films flopping.

Dev said something like he was making the films for the future and they would be discovered by a new generation. So stunned was my colleague he could not ask the question that flashed immediately.

"He was very serious; he thought his films would be welcomed as classics some two decades from now. I wanted to ask him if he is not interested in making films like Jewel Thief or Hum Dono which were appreciated soon after their release," my colleague said.

But he asked Dev Anand if he could not let younger directors make films for him. They could write and direct films which might resonate with a small but influential segment of today's moviegoers.

"What will I do then?" Dev asked, adding something like he felt he was just about 25.

Please click Next to read further...

'Dev Anand was too much in love with himself'

As I mull over Dev Anand's answers, I cannot help but wonder how lucky and smart people like P D James, Max von Sydow and Christopher Plummer are.

They review their plans, ask themselves critical questions, read or watch other peoples work, and we are richer because of their attitudes and resolutions.

We are also lucky that some of the finest filmmakers of our time are making engaging and often provocative films even though they are in their 70s or approaching 80.

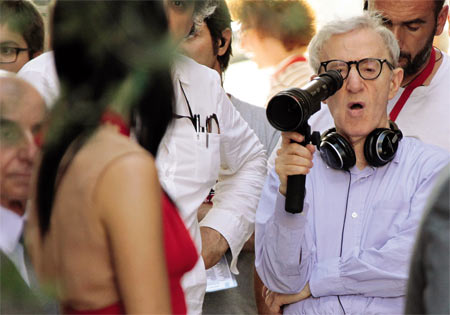

Woody Allen, whose films typically earn around $35 million around the world and recoup the investment because each of his films cost about $15 million, has made one of the most successful films of his career.

Midnight In Paris has not only grossed $150 million worldwide, it has also received strong reviews.

Martin Scorsese has made an eye-popping fantasy, Hugo.

Clint Eastwood has taken a critical look at one of the most influential men in American history, J Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation for decades.

J Edgar, with Leonardo Di Caprio in the title role, is a tautly made film that might fetch Leo another Oscar nomination.

In Portugal, filmmaker Manoel De Oliveira turned 100 last December. He has made 60 feature films and shorts and now is at work on A Igreja, three connected stories set in Brazil following a visit of the devil to earth, a case of adultery and the delusions of an ornithologist.

For over two decades, De Oliveira is mostly wheelchair bound. You seldom hear him brag about his work. His films may not be big box-office hits, but they recover their modest investment and they (like The Strange Case of Angelica) travel to venues like the Toronto International Film Festival

He continues to be a tough critic of the Church and globalisation.

Dev Anand was too much in love with himself, and too blind to his limitations. And we -- even those who did not see his recent films -- are poorer. There is much more to life and creativity than bragging points.