| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Are we artistes or poor people?'

'You go into the colony and people will show you their photographs with Nancy Reagan and Barbara Bush. They have traveled to America as representatives of traditional Indian culture.'

'Then they go back to their slum that is constantly under the threat of being demolished. The police constantly bother them, stopping them from performing on the streets and they are essentially street artists. But their art and their performances have been criminalised.'

Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com meets two American filmmakers who have made an amazing documentary about an Indian slum.

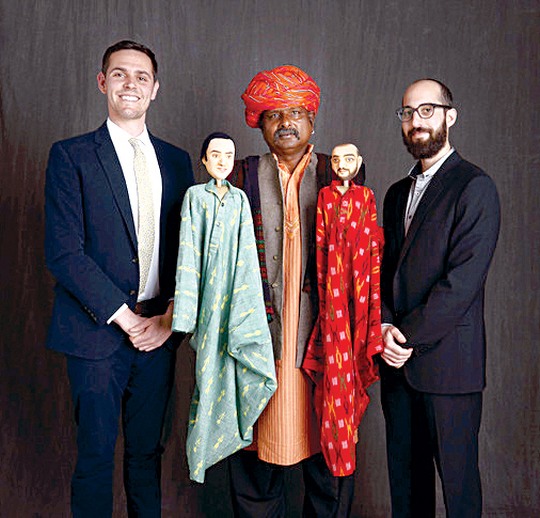

Jimmy Goldblum and Adam Weber are New York-based filmmaker friends who traveled to India inspired by Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children and decided to make a documentary on the lives of the residents of Delhi's Kathputli Colony.

Their film -- Tomorrow We Disappear -- narrates a fascinating and sad tale of artists -- puppeteers, magicians, acrobats, jugglers and others in a slum.

A few years ago, the Delhi government sold the land to a developer, who plans to bulldoze the slum and build the city's tallest residential building. Although alternative housing will be provided to the artists, Tomorrow We Disappear explores their struggle to maintain their livelihood and their art form.

A beautiful, moving documentary, Tomorrow We Disappear had its world premiere at the recent Tribeca Film Festival.

A few months ago, you had told me about being inspired by the reference to the magicians' colony in Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children. Which one of you had read the book?

Jimmy: We both read the book and Adam recommended it to me five, six years ago. When I got to the chapter about Parvati the Witch and Picture Singh in the magicians' ghetto, I thought how the hell did he come up with this?

I found a Times of India article about how the Kathputli Colony (in Delhi) was going to be bulldozed. Which is when I wrote an e-mail to Adam that we should check this out and the idea of the documentary formed from there.

Did you work on projects before?

Jimmy: No, we were college roommates. We have known each other for a long time. I grew up with Adam's cousin. But we had our separate careers and never worked together.

What college was that?

Jimmy: University of Pennsylvania.

And when you wrote to Adam did he immediately say yes?

Adam: You know I think that was the easiest e-mail to respond to. Jimmy and I have this weird relationship. We give each other energy back and forth. So I immediately wrote back asking when can we go?

It only took a couple of months from that time for us to fly to India.

How many trips did you take to India to make the film?

Adam: We made three trips over the course of three years, spending a total of six months there. We also sent a second unit team to capture the recent protests against the demolitions.

Please click Next to see more...

'One of the things I liked about Midnight's Children was the connection India has with folk tales'

How difficult was it for you to access the characters who narrate the story? How did you get them to trust you and speak before the camera?

Jimmy: When we first started investigating the project we were introduced through e-mails and Facebook to photojournalists who had been there and had met one or two people. But we didn’t really know what to expect until we got there. They had seen journalists before so they were very welcoming. But they didn't understand why we kept coming back every day for a long time.

It took them sometime to understand the scale at which we were planning to tell the story and what story we were actually telling.

And how was the experience of visiting a slum in Delhi?

Jimmy: I had been to India before, mostly in Rajasthan. But I was with my family for a month. When you do the tourist route, you are extremely isolated from the real people. But I had the compulsion to go back.

Adam: One of the things that I had liked about Midnight's Children and why I liked going to the colony was that there is still this connection India has with folk tales. There is something magical and these people still play that function that connection with the traditions.

Perhaps I am looking at it from the point of view of an outsider, but their living conditions are quite harsh. Their homes often get flooded.

Jimmy: What we did not report in the film was that there is this modern Delhi and then this slum. But it is a very diverse place. Some people have a rather decent standard of living, while for others it is a lot tougher.

Adam: The structure of the film makes it clear that it is definitely a slum, there's no hiding it. But there's something more to it as well. They have a sense of pride about their homes and how they live.

Jimmy: But for many of them the materiality of life is not important. Their homes may be falling apart, and water often seeps inside. But then one of them will say, 'My father built it' or 'This is the place where we learned our trade.'

Some of these people did sign the contract to move to the temporary housing provided by the developer and yet they do not want to move. What legal ground do they have?

Jimmy: It is something we continue to talk about. If nothing else, then the film should convey that there is a group of artists who are ill equipped at understanding this colossal land deal. It's hard to see what is actually happening.

They signed a paper to allow the transit camps to be built. But I think they had hoped that things would move a little bit slower.

There are some people who have moved to those temporary houses. There are 3,200 families and very few have left. Eventually the plan is to build skyscrapers, a commercial complex and projects like homes for the artists.

There is a lot of irony in the story. Many of these people have won national awards and traveled abroad. But then they are sent back to their homes with really poor living standards.

Jimmy: It's an existentialist crisis for them. You go into the colony and people will show you their photographs with Nancy Reagan and Barbara Bush. They have traveled to America as representatives of traditional Indian culture.

Then they go back to their slum that is constantly under the threat of being demolished. The police constantly bother them, stopping them from performing on the streets and they are essentially street artists. But their art and their performances have been criminalised.

Adam: Slowly they are being stripped of their traditional form of art.

What's interesting about this story is that they are being offered free housing with kitchens and living spaces. In other situations, people will be ecstatic to get housing for free.

But as Puran asks in the film: 'Are we artists or are we poor people?' They will lose the sense of their art if they move into the new flats that look like boxes.