...A hate letter to our system, feels Sreehari Nair.

Our film-makers have India's economic liberalisation to thank for the stock 'Emraan Hashmi' character.

Think about it.

The stock Emraan Hashmi character is a product of his times: The post 1991-period of 'money fever' where values are as quickly eroded as wealth accumulated.

This character (exhibited in Jannat, Crook and such other titles) suggests the price you pay for dreaming above your station; the pride of excessive economic freedom, now about to be shattered.

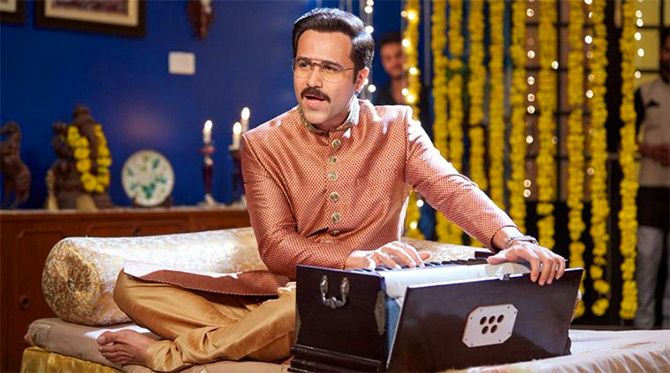

In his latest, Why Cheat India, the stock Emraan Hashmi character gets a reboot as Rakesh Singh, a stylish werewolf of sorts, who prattles on about money, power, and politics -- and occasionally about all three in one quick burst.

A 'fixer' of competitive examinations, Rakesh or Rocky, is like the hero of a sick Western: Someone who knows both sides of the law and is tough enough to go his way.

Quite frankly, I prefer Hashmi letting it rip as this particular character-type than watching him in, say, Danis Tanovic's Tigers.

His restraint in that film, his display of moral scruples, felt like a stunt, not least because we know him as the chief advocate of the crude and the electric.

His best performance to date has been in Shanghai, where he played an inarticulate slob who wasn't denied his intelligence and sensitivity, but otherwise, in the case of Emraan Hashmi, conscience always writes white.

The director of Why Cheat India, Soumik Sen, is delighted to have Hashmi back to where he truly belongs -- the very bottom of the 'ethics pyramid' -- and gives his lead the full star treatment.

Rakesh Singh is a matinee idol in a film of ordinary people; and this motion picture is as much a love letter to Emraan Hashmi as it is a hate letter to our system.

Rakesh does not seem to be talking, but speed-reading his own biography.

His conviction in his 'methods' gives him a kind of rude health: He glows a little.

He smiles, sighs and uses his toothpick like a star.

Even the man's exhaustion is one big number.

Cinematographer Alphonse Roy's camera lovingly circles Hashmi as he unfurls his anti-theories ('When it comes to making money, screw all theories'), and you witness him going from Rakesh to Rocky like that!

This kind of camera deification is apparently still hot, as some reviews of Simmba seem to hint at, but I really don't know what to make of this technique of cinematically celebrating a 'single character' especially in a movie that seeks to espouse public will or attempts to refine mass consciousness.

In such movies, when exactly can we expect deification to stop and democratic leveling of characters to begin?

Hashmi towers through his smartassery and wisecracking, but his acting isn't physical enough -- it does not have tentativeness nor is it exploratory -- for us to feel protective of him. (Or see him as an extension of our own darkest impulses).

The film itself wants to be nothing more than a muckraking expose of the education system, with one eye fixed firmly on the running time. So the idea is to roll out Rakesh's one act of corruption after another -- often fitting them in split-screens when the information gets too dense to be played out in succession -- so that we get to the interval block at the precise instant that Rakesh's first big downfall occurs.

The story isn't allowed to tell itself and the consequence of the breakneck narrative speed is that the scenes often don't mesh -- the perceptions at the end of one scene, are not carried to the next. And worse, most scenes feel like they are missing a 'centre' -- a claim that can be made about the whole movie as well.

When Rakesh sings wistfully for his girl (Shreya Dhanwanthary), you don't even see the point because you have hardly watched their relationship develop. There are two sequences of her looking at him from the corner of her eye, and next we know he is missing her and singing ghazals, all Udhas-like.

The visual atmosphere of the movie never acquires true emotional power.

A shot of Dhanwanthary looking at Hashmi's Rakesh from her terrace is one that implies she is going to fall for him, but we get the implication only because the shot is a cinematic cliché.

The result of Soumik Sen's unabashed loved for Hashmi is that no other actor is given his or her due.

For critics who measure actresses's importance by the number of scenes they appear in, there's Shreya Dhanwanthary standing in your way here, in a full-length role, but stripped of all personality.

Actors's importance in a movie is not be arrived at mathematically, but by how 'charged' their presence feels (Angela Jones had one scene in Pulp Fiction, but don't we remember her, 'What Does It Feel Like to Kill a Man?' as much as anything else in the movie?).

There's no 'charge' about Shreya Dhanwanthary's character or about the character of Satyendra Dubey (Snighdadeep Chatterjee), a boy genius who Rakesh Singh corrupts, and who he pushes down a rabbit-hole of currency and debauchery.

Satyendra Dubey is probably meant to signify the death of idealism, but the illusions and the wide-eyedness of the character are so typical that his final disillusionment does not strike us intensely.

At any rate, this isn't a movie that wants to leave you with anything to hang on to; it's a self-infatuated fantasy disguised as an uncovering of souls, already dead.

That being said, Why Cheat India isn't a bore.

It is lean and not endlessly moralising as, say, 3 Idiots.

Toward the end, the film almost turns into a farce; an exercise in camp with no patience for reformation.

Normally in movies such as this one, when we are introduced to the amoral hero, we know that he will eventually become the most moral of them all. But here, Hashmi's character, Rakesh Singh, is spared of being raised to any standards of socially acceptable 'good' behaviour or our shared ideals.

In resisting the temptation to turn Rakesh into a square, the film, in effect, stays away from becoming a fantasy or an unbearable melodrama.

And that's the best thing to be said about it.

If parts of Why Cheat India hold you, it does so in a sickly, suffocating manner.

This, you slowly realise, is because the movie is not the product of an empathetic research (where the writers and the director have felt and dredged out the depth of corruption and then presented it before you), but that of a defiantly cynical worldview.

By the end, Rakesh Singh, in court, justifies all his acts by bellowing an anti-idealism speech, the gist of which is: 'What is the point? It's all rotten anyway.'

The lawyer (played by Rajesh Jais) then shuts Singh up by reminding him how this attitude had claimed a life. One gets the feeling that without a mention of that casualty, Rakesh Singh would have possibly walked out as the anti-hero for our time.

Driving back home, I started thinking about how slim the philosophical difference between Why Cheat India and a movie like Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi is.

Both films, in a sense, deal with total corruption. But if Why Cheat India thinks of corruption as the final resort of those who have no time for idealism, in Hazaaron, we are shown how corruption is born out of our small desperations; how corruption is often our idealism carried to its very extreme.

This philosophical difference between the two movies becomes the critical difference between great art and a certain grade of convenient art.

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi threw our cynicism back in our faces.

Why Cheat India, true to the nature of its protagonist, uses our cynicism as a security and finally cashes it.

© 2025

© 2025