'The new Indian cinema has still not found its voice and identity. It's trapped under the deadwood weight of Bollywood and popular Indian cinema.'

Dev Benegal started his film career as an assistant director with Shyam Benegal on films like Kalyug (1981) and Mandi (1983). Ten years later he set out to make his first feature -- an English language film, English, August (1994).

Based on a popular novel by a young government official -- Upamanyu Chatterjee (currently joint secretary, Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board -- English, August follows the year in the life a young trainee civil servant and the cultural shock he gets when sent to a small town in India's hinterland. There he learns to become an adult and accept the choices laid out before him.

Like Chatterjee's book, Dev Benegal's film (the two wrote the script together) and especially its ironic humour gained an iconic status as it spoke to a generation of young Indians, educated in English, but sometimes feeling dislocated in their own country.

In 2015, English, August, the film, turned 21, an adult much like its protagonist Agastya Sen. On the film's 21st anniversary Aseem Chhabra spoke to Dev Benegal about the making of the film and what has changed in India's indie film scene since his debut as a filmmaker.

Dev, where do you stand on restoring English, August for DVD?

I was so particular about the storage and the preservation of my film, having seen the state and conditions of the negatives of Satyajit Ray's films when I was working on the two-hour documentary on him (directed by Shyam Benegal). And I swore to myself to never let that happen to my own film if and when I made it.

I made sure to take it to the best lab in the country, which was Prasad Film Labs in Madras. But I didn't realise that this is where my negative will get damaged.

I just thought it was there, in the best lab and stored correctly. I should have checked continuously, spoken to them.

Was this the original negative?

This was the original 35mm negative, because we didn't have the money to make duplicate negatives. And in any case that technology in India was very poor. There was a loss in the quality of the image when you made a duplicate.

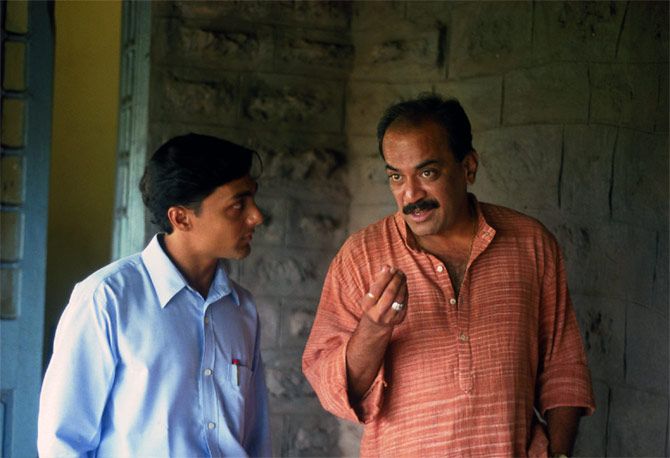

It's really heartbreaking because the film has the work of one of the finest cameramen in the country -- Anoop Jotwani. Anoop was (Satyajit Ray's cameraman) Subrata Mitra's blue-eyed protege. He was really understood what Subratada was about.

In English, August, his work was wonderful -- the depth and tonality that he (Anoop Jotwani) brought to the image, I haven't seen elsewhere.

So what happened to the print?

There are a few prints remaining. One of them is at an archive in Taiwan. Taiwanese filmmaker Edward Yang liked the film and had the archive buy a print. There is a print with the Directorate of Film Festivals in Delhi. And there is a low contrast print with the French television network La Sept-Arte that co-produced the film.

Now I am planning to scan these three prints, and whatever I can scan from the original negative and piece it together.

This is the first time we had recorded digital sound for a movie and that has been stored and backed up. Vikram Joglekar's sound design and recording is intact, as is the music by D Wood and also Vikram.

The real issue is the cost of restoring. It is much higher than what it cost to make the movie. So that is the stumbling block. There are no organisations or funds I can access for support. I really have to fund it myself. I am hoping to do that in small stages and get it done.

I recently saw the restored versions of Wim Wenders' films and Wenders spoke about the German government fund to restore and digitise all their works.

What would be the cost to restore it?

I think it's going to be $200,000 to $250,000, to generate a new negative and make all the material for the DVD, for online streaming.

By the way, I recently saw the restored print of Shyam Benegal's Junoon. It was restored by Kunal Kapoor at Prasad Labs. And it is stunning looking.

That sounds ironic, but I know people get the restoration work done at Prasad Labs. I may have to go back to the same people who destroyed my negative.

Are you planning to do it soon?

I might get it done in a year or two. I get an e-mail everyday from somebody who is looking for the film.

Do you remember the time when you first decided to make the film?

I always wanted to make a feature film. But I did not want to make the kind of films that were being made at that point in India. I felt there was something quite disingenuous about art cinema and the middle-of-the-road parallel cinema.

I wanted to make a film about my generation, the world and characters I knew.

After two years of dropping into classes at Cinema Studies at NYU (New York University), I stumbled across this book, English, August and started reading it one afternoon. I loved the book.

I read it the second time and found it witty and wonderful. The third time read it, I knew this is the film I could make since it was about a character I knew and in a strange way it was almost my life.

It is about someone who is born in free India, he is urban, listens to the same kind of music. Knows about the world without having left the country. It was about the discontent in my generation. It was about the rebel within us.

I had a terrific professor at NYU -- Robert 'Bob' Stam who introduced me to subversive cinema, films beyond Hollywood and European films, cinema from Brazil, Orson Welles' Voodoo Macbeth. All of this was swimming around my head. And when I read English, August, it seemed like the right kind of thing to do.

There was the challenge of making a coming-of-age film that was in English. I emphasised that it was a multilingual film in English, Telugu, Marathi and Bengali. I met Upamanyu and showed him a couple of shorts I made. And we decided to write it together. He has a good cinematic sense and is not attached to his books.

There was a reversal of roles where I wanted more from the book in the film and he kept saying let's drop this and delete that.

You both get the co-writer credit?

Yes. I knew I did not want anyone else to write it. Upamanyu said he had never written a script. I recall telling him, 'Don't worry we'll figure it out in four days.' It didn't take too long to write it. It took a while to get it funded. There was no interest in India and the UK -- even though it was the typical route then.

I spent one year of my life going everyday to NFDC (the National Film Development Corporation), being called in for meetings at 9 am and then made to wait the whole day. It was the most humiliating process in my life. I swore never to work with them ever again, regardless of who takes over.

I almost thought of giving up and doing something else. But then I went out and finally found the French network La Sept-Arte that agreed to finance it.

What about the casting process and how did you find Rahul Bose to play the lead?

We had a long process. Uma da Cunha, my casting director, traveled all over the country -- to Kerala, Andhra, Tamil Nadu, to Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, looking at theatre groups and young actors.

It was the most memorable time we had and Uma always recalls it as one of the best times she had, even though I was very demanding.

Shabana Azmi was very keen that I should cast Aamir Khan in the lead. I went to see him and I had been told I had to narrate the film. I didn't have a clue of what narration meant. So I read the whole script out to him. At the end he said, 'This is a very detailed script. I didn't understand a word.'

Later when I finished the film he actually came to see the film. We went to Eros (a well-known movie theatre in south Mumbai) where it was running for the seventh week. It wasn't a private screening. He saw it and said, 'Now the whole things comes back to me.' He said he couldn't 'see' the film when I was reading the script to him. That was nice of him to say so.

Uma finally said she had found a young theatre actor who had never done a film. I had Rahul Bose read the part and all the while I had my eyes shut. Rahul told me later he was very disturbed, because he was reading the part and I wasn't even looking at him.

My point was that I wanted the character to sound right, like Agastya Sen. It was more than the look. He had to sound true.

What was Rahul's background?

He had done a well-known play. I think it was Are There Tigers in Congo? I did go to see it later. It was good.

Uma also found Shivaji Satam, Tanvi Azmi. We had a terrific cast.

What about the shooting itself?

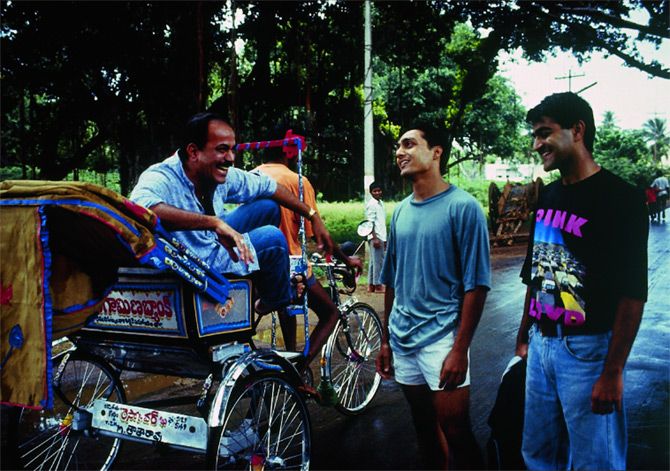

I had shot a couple of shorts in Andhra and I liked the idea of being out of place in a world where you have no sense where you were. It was like being a stranger in your own country, which is what English, August is about.

We got to Narsipatnam, which is way out. There was no phone. It was rigorous shoot and it was very hot. I had a great production designer and a terrific technical team who were great creative collaborators.

I edited the film in New York (with Allyson C Johnson who later cut Monsoon Wedding and The Namesake). Upamanyu and I saw a cut and we were both depressed and almost decided to put it aside as a bad mistake.

I showed the film to the French producers and they seemed happy and then took it for the premiere to the Toronto film festival. I remember calling Upamanyu and telling him there were lines outside the theatre and I was convinced they were for some other film, not ours.

But it was for English, August. The big thing was people laughed. I never expected that.

I still felt the film was too long and came back and cut 20 minutes.

How did you release the film in India? You said it ran at Eros for a while.

It ran for seven weeks in a thousand-seat cinema -- first at Regal (another well-known movie theatre in south Mumbai) and then it moved to Eros.

None of the Indian distributors wanted to touch it. In desperation I decided to show it to some of the Hollywood distributors. I called Fox and there was a young person -- Sunder Kimatrai -- who had come from LA (Los Angeles) to head Fox India.

He watched the film and later said, 'The demographics match.' I didn't even know what demographics meant. So I had to ask him, 'Will you take it?' and he responded, 'Yes, we will distribute it.'

They took it to five big cities and it did really well. It was Fox's first acquisition in India. We were hoping there were smaller cinemas and kept wishing for those.

As a director when you walk into a 1,000-seat cinema, your heart just sinks when you think how will my film fill a thousand seats three or four times a day. And if not, your film is going to be kicked out.

But it was strange how the film impacted so many people. I remember (Sholay's producer) G P Sippy came to see the film at Regal. He later called me and he wanted to meet me, even though nothing happened after that meeting.

Yash Chopra came to see the film. And he loved it. And I still remember he said, 'Tumne haste, haste, sub kuch keh diya (You have said everything with laughter).' Some really unpredictable people saw the film and took to it.

It was quite subversive for that time period -- it had drugs, male nudity, masturbation, and a self-erotic obsession with the body -- all of this stuff. Yet it sort of connected with the generation that saw it.

And then there were filmmakers who were sitting on the fence, perhaps making advertising films -- it triggered them to go out and make their own films. Make films of their own kind or regular Bollywood film.

I remember John Mathew Matthan, who later made Sarfarosh telling me that he was inspired by English, August to make films. There was Kaizad Gustad (Bombay Boys and Boom).

That was such a different time period and yet things worked so well for you with the French financing and Fox distribution. But what has changed since then, in terms of the quality of indie films -- and there are many more being made now, and the process of making of the film.

There has been a complete revolution in terms of filmmaking. The kind of constraints I was facing -- it wasn't as bad as the 70s -- but you still could not get enough film stock, sound-editing technology was rudimentary and poor.

The financing was impossible. You couldn't even get a silent camera. It was difficult to do synch sound. We were actually able to get one silent camera in Madras with two or three lenses.

Today technology has democratised the process. Anybody can pick up a small still camera, which you can buy off the shelf and which will have advanced filmmaking capability. Distribution has opened up also. You can self distribute.

People are more open to films like this. They have seen films that have worked and there is a track record.

Financing has changed. There is so much more money in the game now. There are many creative ways people are financing now, which didn't exist at that time.

But what about the kind of films that are being made?

So on one hand there is an overhauling and re-writing of the ways in which indie films get made. And that should typically allow for a new kind of exploration of stories and subject matter. But only a few people are doing it.

People are taking fewer risks -- like those that were taken earlier -- and this is so even among the younger filmmakers. Their movies are more mainstream and very few are trying to find a new language.

But you have films like Court or Gurvinder Singh's Chauthi Koot.

The two examples you give are exactly the ones I was going to mention. Both these films are influenced by European cinema. Which is not to say that they aren't good films. They are just two films we can talk about and that's a very tiny number from among a thousand made every year.

The new Indian cinema has still not found its voice and identity. It's trapped under the deadwood weight of Bollywood and popular Indian cinema.

The problem is that we are really a commercial industry, and everything revolves around the box office and the stars.

I think if you think of recovering the money first, it clouds everything else.

If you look a film like Court, it will recover its money, it will make money, because he has stuck to his original idea of what he wanted to do and did not stray from it. It has an integrity of voice and tone.

Second, there is also no real debate around films. It is very restricted.

And finally there is very little film education. Given that we are making 1,000 films a year, we have about three or four good film schools. Whereas in the US every university has a film school.

© 2025

© 2025