| « Back to article | Print this article |

The Classic Dilemma of Being Manna Dey

That Manna Dey lingered for so long -- before the end came -- is symbolic of his remarkable staying power in life as in death.

With ‘Padma Bhushan’ Manna Dey no more, he is much more. He becomes the last of our vintage-era playback singers to leave the scene.

Shamshad Begum ‘of the transparent voice’ -- as the one who died but recently -- was, at the time she passed away, the seniormost of our phenom playback singers as a lady a year older.

Manna Dey’s following her so soon means that the vacuum in the golden era of our playback singing is complete. We shall never again see the like of Manna Dey as he was all voices rolled into one. That he still never went to number one is the grim irony of Hindustani film music.

At this sensitive stage, listing his litany of tunes would be akin to gilding the lily. That kind of exercise is something that anyone writing on Manna Dey, right now, would be undertaking. As I view it, his song vocabulary is too vast to condense into a mere article while taking creative stock of his repertoire.

Click Next to read more.

Raju Bharatan, doyen of India's movie journalists, is the author of Lata Mangeshkar: A Biography (UBSPD; 1995); A Journey Down Melody Lane (Hay House; 2010); and NAUSHADNAMA:The Life and Music of Naushad (Hay House; September 2013).

How Manna Dey missed the chance to move to the top

Therefore I turn the spotlight on a career-determining aspect of his music articulation: how Manna Dey, somehow, missed the chance to move to where he truly belonged -- at the very top, alongside Mohammad Rafi. Kishore Kumar, in terms of musical grooming and background, was equipped to compare with neither Mohammed Rafi nor Manna Dey.

Manna Dey’s landmark songs -- and they are legion -- are firmly fixed in the memory bank of his admirers. Such evergreen numbers as Aye mere pyaare watan (from the 1961 Kabuliwala) drive home, feelingly, the fact that Manna Dey -- given a throat supple as supple could be -- should have been at the pinnacle.

Why did Manna Dey remain admired but never adored?

How Manna Dey faced this positional frustration all through his singing life, is a conundrum that I examine by concentrating on the six build-up years to his career. Years during which his eloquence of expression was almost on a romantic par with that of Mohammed Rafi.

I mean the 1953-59 span during which Manna Dey looked poised to break through as the voice of any of our many top-rating romantic heroes. As a voice entrancing enough to compete, if not with Talat Mahmood, then certainly with Mukesh, Hemant Kumar and Mohammad Rafi.

Those were the three playback performers on a popular par at the 1955 cut-off point that saw the rise of Shanker-Jaikishan and O P Nayyar as hit-parade threats to the suzerainty of Naushad and C Ramchandra.

This, while Anil Biswas and S D Burman; Roshan and Madan Mohan; Hemant Kumar and Salil Chowdhury; Vasant Desai and S N Tripathi were all quality composers simultaneously drawing upon the musical fount that Manna Dey symbolised.

In such a competitive singing setting, the poser of posers: Why did the top reaches of popular esteem elude Manna Dey? Why did he remain admired but never adored? Adored as were Talat Mahmood, Mukesh, Mohammad Rafi and Hemant Kumar, each with a following all his own.

Feast of Classical Music

Take the classic case of the Nimmi-Shekhar February 1953 starrer Hamdard in which Manna Dey was under the baton of the redoubtable Anil Biswas.

Such was the quality of the film’s score, as vocally thematised by Manna Dey, that The Times of India -- unusually for it -- titled its review: ‘Feast of Classical Music by Biswas in Hamdard.’

Manna Dey came in for matching praise with Anil Biswas in that hallmark review -- one of her last -- by the legendary Clare Mendonca (after whom the Filmfare Awards were originally named ‘The Clares’).

Special kudos was lavished by Clare on Manna Dey for his four-way Hamdard Anil Biswas duet with Lata Mangeshkar (on Shekhar and Nimmi), Ritu aaye rutu jaaye sakhi ri.

Here was a tone-setting composition in which Manna Dey (with the mesmeric Lata for company) explored, by ‘seasonal’ turns, the contours of Raag Gaud Sarang, Gaud Malhar, Jogiya and Bahar.

The song ranks as an all-time ragamalika noteworthy for Manna Dey’s limpid rendition.

Yet, in the far more popular Lata-Mohammed Rafi ragamalika from Suvarna Sundari (October 1958), Kuhu kuhu bole koyaliyaa, we have the clue to where that singing giant forged ahead of Manna Dey. Actually Lata is in ethereal voice in both ragamalikas, so where lay the difference in terms of the scale of popularity attained by Rutu aaye and Kuhu kuhu?

Manna Dey seldom excelled Rafi in mood singing

The fluidity of Mohammed Rafi’s vocals made all the difference -- Manna Dey could clearly not eclipse his populist sway. Rafi, in the case of Kuhu kuhu bole koyaliya, was in the composing care of Adi Narayan Rau, the venerated husband of Suvarna Sundari heroine Anjali Devi. She and the Adonis-like Akkineni Nageswara Rao enact the Kuhu kuhu duet sung by Lata and Rafi.

Adi Narayan Rau begins Kuhu kuhu in the Carnatic Hamsanandi (approximating to the Hindustani Sohoni) and, from that point, leaves the enchanting raag-weaving tapestry as a specialist job to be undertaken by Lata and Rafi.

The song epitomises the popularity stakes’ race that Manna Dey ran with Mohammed Rafi and never really won in the public imagination.

Maybe Manna Dey excelled Rafi all the way in kite-flying, but seldom in mood singing. 'Dada, how do you manage to let your voice soar with such ease?' enquired Rafi of Manna, deferentially. And then proceeded to get his own voice to soar some more.

Manna Dey thus discovered that Rafi had attuned his vocals to romantic film singing in such a way that the Bengal titan’s being the superior classical performer gave him no real competitive edge. If anything, it was his classicism that held back Manna Dey. A Manna Dey who, as he moved on, was observed to be singing less and less for a top hero and more and more to vibe with the vocal gimmickry of a Mehmood.

Manna Dey, in truth, loathed himself for this. All the more so when, during morning walks in the Bengali-dominated suburbs of Khar-Bandra, he met Calcutta intellectuals who demanded to know if he really needed to descend to Mehmood’s level at that advanced stage in his career.

Following this, Manna Dey, around 1967, even asked me if he should be giving up on Mehmood. “You must do nothing of the kind!” I said. “Just keep singing and who knows what opportunity opens up when?”

Such an opportunity presented itself when Papa S D Burman being seriously ill, Pancham (R D Burman) -- as chief assistant -arbitrarily replaced Mohammed Rafi with Kishore Kumar on Rajesh Khanna in Shakti Samanta’s pathbreaking Aradhana (September 1969).

Outcome: it was now Kishore Kumar who shot up -- after 21 years of playback struggle -- to overcome the pre-eminence of Rafi. Thus Rafi, come 1970, no longer led the field, so that was the moment for Manna Dey to let music directors know that he was ready to take over -- for starters -- the number two spot rendered vacant as music director after music director proceeded to indulge Kishore Kumar as his latest vocal fancy.

As Kishore Kumar’s vocalising rose to a new peak, the spot after his was there for Manna Dey. All the more so as Mahendra Kapoor, even after a full 10 years in films, could not quite make the number two cut ahead of Mohammed Rafi.

Manna Dey made no visible professional move to assert his established class

But Manna Dey made no visible professional move to assert his established class at this important juncture of his career in end-1969. He made no attempt to emulate Mohammed Rafi who, by mid-1953, had quietly projected himself as the alternative to Talat Mahmood and Mukesh, who had progressively eliminated themselves by opting to turn singing stars at their playback zenith.

Manna Dey, by contrast, was astonishingly laidback at such a propitious turn in his career (during September 1969) and just let things slide. It was almost as if Manna Dey had expected the mantle of Mohammed Rafi to fall into his lap as his vocal right. And consequently, it was Kishore Kumar who zoomed to the top.

Manna Dey rationalised this moment of inexplicable inaction by later noting in his (2007) Memories Come Alive: An Autobiography: ‘Rafi was, naturally, quite disheartened by the way he had been sidelined from his once-prominent position. Had he come to terms with the capricious ways of a transient world and decided to be content with the public adulation he had once enjoyed, he would not, perhaps, have suffered quite so much over his rejection and ended up so bitter over the whole affair.’

There you get to the nub of what held Manna Dey back. Not only did Manna Dey now not want to join issue with those ranking after Kishore Kumar, to grab the number two spot, he even expected Rafi to accept his loss of primacy philosophically.

Was it the fact that Manna Dey had never reached the number one slot that acted as a deterrent here?

Rafi, on the other hand, having been there, wanted urgently to get back.

Rafi might or might not have got back. But at least he was not prepared to give up without a fight.

Manna Dey, on the other hand, just accepted things as they came. Therefore, only so much, and no more, came to his lot. He remained the supreme classicist to be reduced, with the years, to something of a status symbol.

Manna Dey was all confidence one moment, full of doubt the next

Mohammed Rafi became almost a complex with Manna Dey.

Where did this Rafi preoccupation begin? You get a hint of it as Manna Dey writes about serving as an assistant to his composer-singer uncle, Krishna Chandra Dey. In the case of ‘a wonderful composition he had been teaching me with painstaking care’, Manna Dey says that he was told by his uncle: ‘ “I would like Rafi to sing this number. Get in touch with him tomorrow and ask him to come for rehearsals till he has mastered the song thoroughly. Then we will record it.”

‘I was crestfallen,’ observes Manna Dey. ‘Why wasn’t Uncle (Blind Singer K C Dey) allowing me to sing this fine composition -- I could certainly sing it better than Rafi. Unable to contain my feelings, I blurted out: “Can’t I be allowed to sing this song?”

'Absolutely not! You can’t possibly sound like Rafi!' was K C Dey’s response.

"I was heart-broken," adds Manna Dey. "Rafi Miyan turned up next day and it was I who had to teach him the tune. Considering how I felt about the whole situation, it was terribly difficult for me, but there was no escaping the hated task. I was infuriated by what Uncle was putting me through. But, once Rafi started recording the song, I knew that Uncle was right. I had been quite mistaken. I could not have sung that composition better than Rafi -- at least not at that time."

There you have it.

Manna Dey is all confidence one moment, full of doubt the next. This was as early as 1943, when Mohammed Rafi, too, was a comparative fresher.

Manna Dey let Kishore steal musical scene after musical scene in Ek chatur naar

Indeed, in his autobiography, Manna Dey, incredibly, even suggests that Kishore Kumar marched ahead of them all (by end-September 1969) because his style of singing put even a classical colossus like him on the defensive.

Was this the same Manna Dey speaking who (early in 1968) had refused point blank to sing, on Mehmood, Ek chatur naar when Pancham mooted the idea in Saira Banu-Sunil Dutt’s Padosan? Upon Pancham spelling out that Manna Dey on Mehmood, in the grand sum, would have to be losing out to Kishore Kumar (as Sunil Dutt’s ventriloquist in Padosan), our Trojan told R D Burman to get lost.

“Now you want to heap the ultimate humiliation upon me by making me out to be a classically inferior singer to Kishore Kumar, is it?” sharply queried Manna Dey.

Whereupon Kishore Kumar rang Manna Dey and explained that it was designed to be no more than a screen happening.

“In fact it is you who have to guide an unschooled ignoramus like me, Dada, on how to so perform, classically, as to not look totally outclassed by a singer of your dimension on the Padosan screen.”

Manna Dey then temporised and let Kishore steal musical scene after musical scene in Ek chatur naar. Here is where Manna Dey should have stuck to his no-concessions-to-Kishore guns if he ever expected to displace a Mohammed Rafi from the saddle at the time (early 1968), with even Mukesh (after Milan in 1967) being purely token competition.

Shanker had always fancied Manna Dey

But Manna Dey later (in 2007), actually made the whole Ek chatur naar face-off sound even more farcical than it had looked on the screen, by venturing to suggest, in his autobiography, that Kishore Kumar with his ‘voice throw’ on Sunil Dutt, won through in Ek chatur naar because he was the more resourceful performer of the two!

Maybe that was written at a time (2007) when Manna Dey had seen it all and heard it all. But it raises the gut issue of whether Manna Dey ever really felt like taking on Mohammed Rafi. For, if he was going to yield the Ek chatur naar palm to Kishore Kumar even before Aradhana transpired, where was the question of his ever getting to be in the same competing league as Mohammed Rafi?

It has been suggested that Dame Luck never took Manna Dey in her embrace. Well, this is a level playing field in which you make your own luck. In such a setting, let us return to the situation as it prevailed after Hamdard (February 1953).

That had been the hour when fortune so favoured the brave Manna Dey that he really looked like making it. Raj Kapoor always did recognise Mukesh as his vocal soul on the silver screen. But the coin rolled Manna Dey’s way, for once, as Mukesh banished himself from the playback scene by opting to emerge as a singing star with Mashuqa (1953) opposite Suraiya.

That film was being made by a so-called princess who charmed the handsome Mukesh. In fact Mukesh became so infatuated with that mock fairy-tale princess that he signed a contract with her to sing for no film until her Mashuqa obsession with him was over. After he recorded (late in 1952) Mera joota hai japani and Ramaiyya vastavaiyya for RK’s Shree 420 (to come late in 1955), Mukesh gently let it be known that these two would be his last songs to go on Raj Kapoor for some time to come.

Upon learning about the real reason for such a startling pronouncement, Raj Kapoor was livid with Mukesh. But even RK had to be resigned to the ground reality upon being told that Mukesh had already signed on the fated Mashuqa line.

That is what opened up the chance of a lifetime for Manna Dey, and this gifted singer grabbed the RK mike with both hands to give exquisite expression to Pyaar huuaa ikraar huua (with Nargis-Raj); Dil ka haal sune dilwala (on Raj); and the no less Mud mud ke na dekh (duet with Asha on the same Raj playing up to Nadira).

Shanker (of the Shanker-Jaikishan team), tuning all three numbers, had always fancied Manna Dey.

A great singer is what Manna Dey remained -- to the end

Yet Shree 420 -- beginning with Mukesh going so evocatively on the ‘Eternal Tramp in Raj Kapoor as Mera joota hai japani -- was set to witness that RK favourite scoring afresh, no less tellingly, on the same Raj in the film’s climax -- via Maine dil tujh ko diyaa.

In AVM’s Chori Chori that followed in October 1956, there was no Mukesh around any longer to steal Manna Dey’s Raj Kapoor thunder. Right royally here, therefore, did Manna Dey score on Raj Kapoor (opposite Nargis) via Shanker’s Yeh raat bheegi bheegi; Jaikishan’s Aa jaa sanam; and Shanker’s Jahaan Main jaati hoon.

Even in the case of Jaikishan’s Raag Pahadi Binaca Geetmala topper on Nargis,Panchhi banun udti phirun, Manna Dey was on the button with his timely interpolation of Gillori. As Chori Chori won for Shanker-Jaikishan their maiden (1956) Filmfare Award, Manna Dey, who was at that make-or-break point, looked set for further romantic singing laurels on more and more top-flight heroes.

Raj Kapoor had been a prize Manna Dey catch, considering that Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand, who completed the famous triumvirate, never flipped for him. It was therefore wretched luck for Manna Dey that Raj Kapoor and Nargis chose that late-1956 Chori Chori moment to break up.

In such a milieu, RK’s Jis Desh Men Ganga Behti Hai was a full five years in the coming. In that long interregnum, Manna Dey got eased out as Mukesh returned to the RK fold as the first choice of Shankar-Jaikishan for RK -- as always.

Still Shanka-Jaikishan’s talented assistant Dattaram, composing for Parvarish (May 1958), did offer Manna Dey a further opportunity to vindicate himself as a romantic on Raj Kapoor (opposite Mala Sinha this time) via the Masti bhara hai samaan duet with Lata.

There was also, here on Raj Kapoor, the catchy nightclub duet (with Lata), Beliya beliya beliya beliya. But the deciding climax song from Parvarish, unspooling in perennial Raag Yaman on Raj Kapoor as Aansoo bhari hai, was reserved for the poignant voice of Mukesh. So that, yet again did Manna Dey (in Parvarish) remain unfulfilled as a Raj romantic.

Such a romantic aura, remember, was the key to Manna Dey catching up with Mohammed Rafi, hence the emphasis here on this facet of his singing. My point is that, so long as you fail to assume a romantic-hero vocal imagery on the screen, you remain a great singer, not the voice supreme. So a great singer is what Manna Dey remained -- to the end.

What made Manna Dey nervous

Mohammed Rafi had come through as the classical voice of Bharat Bhushan -- in memorable Naushad custody -- with Baiju Bawra (October 1952).

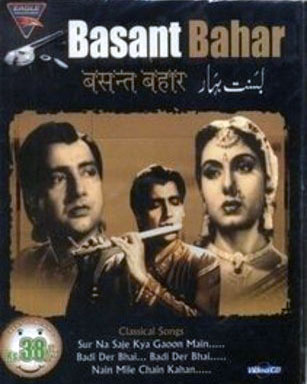

As Shanker-Jaikishan endeavoured to ‘do a Baiju Bawra’ with Basant Bahar (December 1956), Manna Dey had his big chance, in that class movie, to prove himself on the ‘courtly’ Baiju Bawra hero, Bharat Bhooshan, in competition with Mohammed Rafi.

That Basant Bahar bombed was hard lines for Manna Dey as he truly underlined his calibre in that stately show with Sur na saje, Bhay bhanjana and Nain mile chain kahaan (duet with Lata on Nimmi and Bharat Bhooshan).

Manna Dey’s litmus test, however, was to come in Ketaki gulaab juhi from Basant Bahaar, setting him up in climactic competition with Bhimsen Joshi, no less.

Here is where Manna Dey displayed a touch of ‘nerves’ initially.

But his erudite Keralite wife, Sulochana Kumaran from Cannanore, was having none of it.

As Manna Dey wavered, Sulochana told him, point blank, in flawless English: 'You must accept this offer. It’s a heaven-sent opportunity and under no pretext are you to let it go. You are well zersed in classical music and singing that song (Ketaki gulaab juhi) will be no problem for you at all. What is more, the film’s hero (Bharat Bhushan) will be singing the song on the screen and winning the singing contest, according to the script. So what is there to be afraid of? I’m not about to accept your lame excuses. Go ahead and say ‘Yes’. Take it as a challenge and try overcoming it. I am positive you will end up a winner.'

Manna Dey never had a clear romantic run

The way Manna Dey took Ketaki gulaab juhi to a new Raag Basant high came as a refreshingly stunning revelation to viewer-listeners. That, for all that, Basant Bahar collapsed at the turnstiles, was bad luck for Manna Dey. He was denied the opportunity of asserting himself as the romantic winner on such a talismanic hero of the Hindustani screen as Bharat Bhushan.

What we thus see is that Manna Dey never had a clear romantic run except in Chori Chori (October 1956), where he proved himself equal to the best male voices in our films. Shanker -- who was to give his career a fillip -- summed it up succinctly when he observed:

“You know how those comedy songs on Mehmood were time-consuming to record, so that Manna Dey, as my pet performer, was the ready choice. But I could get Rafi to do it equally well if that singer felt inclined to put in the time and the effort. Rafi did feel so disposed, in Gumnaam, when told that Mehmood would be his co-singer. The outcome was Hum kaale hain to kya huwa dil wale hain. This one I found Rafi to be doing with the same vocal flair and flexibility as Manna Dey. That was when I realised that we were wasting Manna Dey in this style of singing involving vocal gymnastics at best. But it was too late, by then, for Manna Dey to change course. By that stage [1965], Manna Dey had become so set in his singing ways that I thought it best not to tinker with his unique technique.”

It is this technique that we saw at play when, as early as January 1954, Manna Dey, in RK’s Boot Polish, so cutely rendered, in Raag Adana, Lapak jhapak tuu aa re badarva (on David).

In effect, therefore, Manna Dey, in Padosan (1968) on Mehmood, was still doing what he had already expounded on David in Boot Polish(1954). Any wonder his vocal calisthenics came to be taken for granted by that late stage?

Another example from a variant genre. How charmed we remain, to this day, by the form and meaning that Manna Dey gave to Ravi’s Raag Pilu heart-warmer, Aye meri zohrajabeen, in Yash Chopra’s Waqt (October 1965). If this one was on ‘Lala’ Balraj Sahni vis-à-vis Achala Sachdev, it was Shanker who had presented Manna Dey on a different kind of hero in Balraj Sahni (vis-à-vis Nutan) in Seema (1955) via Tuu pyaar ka saagar hai. From one Balraj Sahni to another had Manna Dey moved, but not far beyond in ten deciding years. For all his virtuosity, Manna Dey’s vocals could never be readily fitted on the conventional hero in top-class films. This was the roadblock to his reaching the forefront.

Naushad said Manna Dey's voice was "too dry" to suit the sensitive-hero image

Recall how on a Shammi Kapoor -- when that hero was already screen identified as his own leading man in Ujala (September 1959) opposite Mala Sinha -- Shanker-Jaikishan tried out Manna Dey in a big-big opening. This, via Sooraj zara aa paas aa and Ab kahaan jaaye hum (both on Shammi Kapoor); alongside -- on the same cult hero pairing with Mala Sinha -- Jhoomta mausam mast mahina and Chham chham lo suno chham chham (both by Manna Dey with Lata & Chorus).

Yet, Manna Dey failed to cut through on Shammi Kapoor in Ujala (September 1959), as on Raj Kapoor earlier in Parvarish (May 1958). In both Parvarish and Ujala,Mukesh materialised at crucial times to yet again hijack the Manna Dey show.

Was it then written in his stars that Manna Dey’s voice will never be used on top stars in top-class films?

Naushad said his voice was “too dry” to suit the sensitive-hero image. Dada Burman was insistent that Manna Dey, by temperament, was suited mainly to classical performing. In a Rafi-dominated (February 1960) presentation like Kala Bazar, Dada Burman did try out -- without success -- Manna Dey on Dev Anand via Saanjh dhali dil ki lagi (as a duet with Asha Bhosle going on Waheeda Rehman).

Manna Dey failed to come off on Dev Anand in Kala Bazar. A month earlier in the same year, 1960, Manna Dey sang the duet Chaand aur main aur tuu with Asha Bhosle for Manzil, again with the eternal romantic Dev Anand, and Nutan.

The Chaand aur main aur tuu song was a fleeting hit, but the film Manzil was a spot flop! One way or another, Manna Dey was destined to remain set in a classical groove under Dada Burman via the 1963 Meri Surat Teri Ankhen all-timer asPoochhon na kaise maine rain bitaayi.

If tragic was the mould in which Ashok Kumar was cast here, no less tragic, in a sense, was the singing career of Manna Dey. As the best of them all. And yet no better than a vivid illustration of the title adorning the R K Nehru book Nice Guys Finish Second.