Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York

'A lot of people think violence is strong in my movies, but they aren’t actually seeing it.'

'A lot of people think violence is strong in my movies, but they aren’t actually seeing it.'

'Even the beheading scene in Gangs Of Wasseypur is not there. The camera is behind the person and all you see are his hands moving.'

'The imagination makes the audience think they actually saw the beheading and they are completely shaken by it.'

Anurag Kashyap, in an exclusive interview.

Anurag Kashyap recently attended the New York Indian Film Festival, where his film Ugly was premiered.

Ugly has dark and violent tones, and deals with the kidnapping of a little girl in Mumbai.

Kashyap has delayed the release of the film in India after he filed a lawsuit against the Indian censor board for their rule that requires all films to carry anti-smoking messages.

Ugly follows the similar track of Kashyap’s works -- from the early films (Satya, where he wrote the script and Black Friday, which he directed) to his five-plus-hour long magnum opus Gangs of Wasseypur -- large ensemble cast of relatively unknown actors who play realistic, brutal characters.

Kashyap speaks to Aseem Chhabra about his fascination with violence on screen.

A few years ago at the Toronto film festival, I was going to watch a romantic film at 9 am and you stopped me and suggested we should see a horror film…

Julia’s Eyes.

Yes. It was very intriguing film. My question is: Why are you drawn to those kinds of films?

I don’t know, because when there is actual violence in front of me, I can’t see it.

Real life violence? If there was a car accident on a Mumbai street and someone was bleeding?

I saw one accident and I fainted. I was 19 then.

.

'You are tempted to violate the audience watching the film'

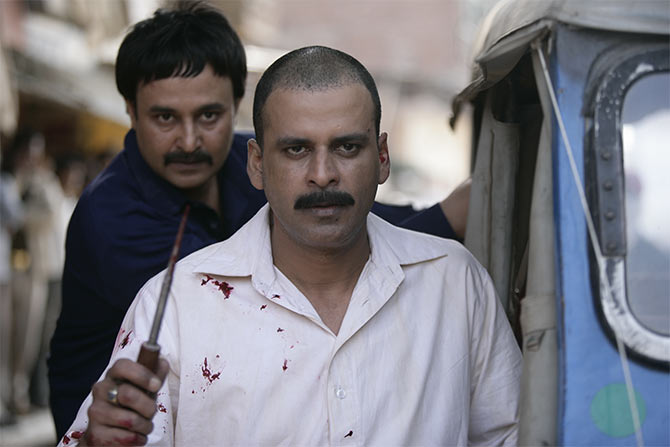

Image: Jameel Khan and Manoj Bajpayee in Gangs of WasseypurAseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York

That’s interesting. Alfred Hitchcock talked about his fears. When he was young, his father left him in a jail for one night. So as an adult, he enjoyed scaring other people.

It’s not that I enjoy it. I have a fascination for violence of all sorts, not just physical violence. If you look at it carefully, baring a few scenes in Gangs of Wasseypur, in all of my other films, the violence is always off screen.

You are tempted to violate the audience watching the film. That’s why I show off-screen violence because people need to wake up. They need to be drawn in. They are very happy and content with the way things happen in the expected way.

Earlier this evening, I was listening to a discussion after the screening of Fandry (National Award winning Marathi film), and one person was saying that she didn’t want the young boy to be beaten up. He had all this rage and we knew someone was going to beat him up. The film ends with a moment where you do not see the rest of the action. That’s the most effective way of using violence.

A lot of people think violence is strong in my movies, but they aren’t actually seeing it. Even the beheading scene in Wasseypur is not there. The camera is behind the person and all you see are his hands moving. The imagination makes the audience think they actually saw the beheading and they are completely shaken by it.

But when you are writing your scripts and shooting, is it actually fun, because you know the playing with the audience’s imagination?

I choreograph all my violence scenes and try and do long takes. I try not to use it as a gimmick, where you cheat. Otherwise, the edits make it look exciting.

'There hasn't been a single time when our society or the world hasn't been violent'

Image: Tenzin Yeshi Paichang as the young Dalai Lama in KundunAseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York

Martin Scorsese, who is messiah of violent films, made a film like Kundun, about the Dalai Lama.

He’s actually like a child and his dream project, which he is making now -- Silence -- is about a missionary who is persecuted in Taiwan. Scorsese was that kid on the block who would run away from violence.

That’s what Mean Streets was about.

And he would hide in the church. People, who participate in violence, usually go see a comedy film. Only a guy, who watches it from a distance and is so bothered by it, would be the one to recreate it.

Kundun was a beautiful story about the early life of the Dalai Lama. Would you consider making a calm and quiet film?

The next film that I am writing is a very emotional one, a simple story about a father and a daughter.

Do you think -- not just in India, but everywhere -- we live in a violent society? If there is a car accident in India, people immediately start to beat up the driver.

There hasn’t been a single time when our society or the world hasn’t been violent. It was always like that. Centuries ago, it was far worse. But we live in denial and I think sometimes it is important to address it in a serious way.

When the mob collects, they always beat up the weakest. Each individual in the mob, his or her individual rage is coming from somewhere else. It is the same rage that brought people to the streets against the anti-corruption movement.

Yet, it’s a fact that no one in India will stand in a line. We protest against corruption, yet everyone wants someone inside. India is the only country where people ask me how I got into the movies, whether I knew someone. Where does that question come from? No one wants to take the hard way.

And then we become so moralistic about the world. We are the second most populated country in the world and we have such a problem with sex. We are a strange bunch of people.

'Every character is good and bad as well'

Image: J D Chakravarthy, Sushant Singh and Manoj Pahwa in SatyaAseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York

The reason I ask these questions is because Bollywood always had a villain like Pran and Prem Chopra. But you wrote Satya and that was very real. It actually made us feel uneasy.

When it is black and white, and good will win over evil.

But the moment there are situations in gray, people get bothered by it. So whether it is Bhiku Mhatre or Bhau (characters in Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya), each of them is vulnerable and has a darker side. Every character is good and bad as well. As an audience, you can’t take sides and you get very uncomfortable with that.

You went to Scindia School and Delhi University. How did you know these characters in Satya?

It was a very simple approach. We were making a film about a business household, where the owner of the company is Bhau and people working for him are like Bhiku Mhatre. It’s just that their business is extortion and murder, and the people are from the streets.

Otherwise, they are normal people, with homes and families. What Bhiku does is to go to work everyday and then return home. His work makes him a criminal but we approached the characters like normal people.

That’s like the criminal in Goodfellas, who eats breakfast at home after a violent night out.

What they chose to do for their profession, I would not have the courage to do. But they made their choice out of desperation, frustration or just because of kinks.

We didn’t have to research the psychology of a gangster because it is very similar to anybody else. A gangster goes for his first kill just the same way as a banker goes to collect investment money from someone for the first time.

But that scene where all the gangsters are sitting and drinking is so believable.

It is believable because it was completely improvised. It’s like the police station scene in Ugly (at the beginning of the film). It was not written. I went and told each of the actors their motivations. You have to see the first single shot we took. It went on for 14 and half minutes. Eventually, I took different shots, as I couldn’t have the scene go on for that long.

'I am a child of Scorsese, who fantasizes about Tarantino'

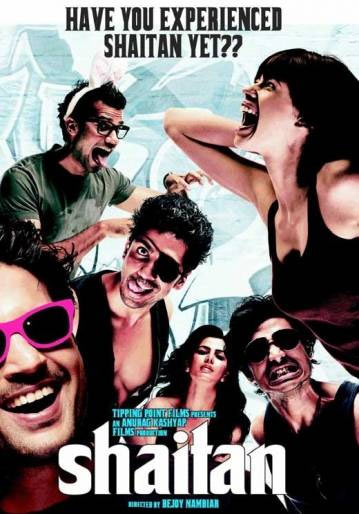

Image: Poster of SahitanAseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York

You have been doing such great work encouraging younger talents. But many of the films like Shaitan, Peddlers and Monsoon Shootout have crime and violence as the focus. There is an expression I use in my head that here are the children of Quentin Tarantino in India. His works became the inspiration for so many indie films in India. Am I right?

I don’t think I am child of Tarantino. I am a child of Scorsese, who fantasizes about Tarantino.

But there is a new generation -- I call them the generation of Torrents. They have no money in their pocket but they want access to world cinema, which our country and distributors would never release. And Torrents gave them access to it.

Go down to Tamil Nadu and see the incredible movies being made there. Also, in Marathi cinema. And this generation is changing cinema. That is also happening in Hindi films now.

And Tarantino wasn’t the only one making violent films. They started watching Korean, Chinese and Hong Kong films.

But are these films organic to India storytelling?

There is more Indian story telling in regional cinema. What Marathi cinema is doing is the real India.

What Tamil cinema is doing, portions of it are hard to deal with. When you see Vetrimaaran or Subramaniapuram, they are talking about a South India, which is obsessed with cinema. At the same time, they have violence in their everyday life. And they are rooted there because they have to use their language.

It’s different with Hindi films because that cinema has become more urban and most of the Hindi filmmakers write in English. So their films tend to be more westernised, barring a Tigmanshu Dhulia, who is very rooted.

Also, unlike the Hindi filmmakers, the Tamil directors are not aware of an international audience. They only care about the local audience. Hindi filmmakers want to reach out to a larger audience and so they may have a western way of story telling.

'The human mind is more imaginative and darker than what we see on the screen'

Image: Manoj Bajpayee in Gangs Of WasseypurAseem Chhabra/Rediff.com in New York

When you come to New York, what kind of films you like to see?

I see all kinds of films. I saw Raid 2, Only Lovers Left Alive and Grand Budapest Hotel.

I wanted to touch on Gangs of Wasseypur, especially Part 2 and go back to violence. How did you decide how far you go with the violence?

It’s based on the story.

The man was killed with 700 bullets and when the police came to pick up the body, the hand just came off. They had to eventually pick up the body with shovels. They refused to do post-mortem on the body.

Even Manoj Bajpayi’s killing in the first part, he was at a petrol station. Munawar Khan was shot just like that, and he went on a rickshaw with a bullet in his head. He died in the rickshaw. And it happened in a marketplace. So it was all a recreation of what actually happened.

I just made it more dramatic and cinematic.

You talked about off-screen violence. Michael Haneke’s Funny Games is perhaps the only violent film I have seen that was very hard to watch. In the scene where the kids are being beaten up, you don’t see the violence, you hear the sound and the blood splashing.

That is actually more violent. Because the human mind is more imaginative and darker than what we see on the screen.

And people are bothered by their own possibilities.

Comment

article