| « Back to article | Print this article |

Cannes 2014: Of winners, Indian presence and the fest's rich history

All the buzz from the recently-concluded French Film Festival.

As near a consensus as ever possible in Cannes was reached last night when a remote part of Anatolia, Turkey, hit centre stage in the vast Palais du Festival.

The golden Palme d'Or was awarded to director Nuri Bilge Ceylan for his Winter Sleep.

"At last," he may have breathed, striding up to the stage amid a sustained roar of applause.

He has won everything else over the years at this festival.

Ceylan dedicated the award to young people in Turkey, many of who have fought and died for freedom of expression in recent years.

Please click NEXT to read further.

The big winners

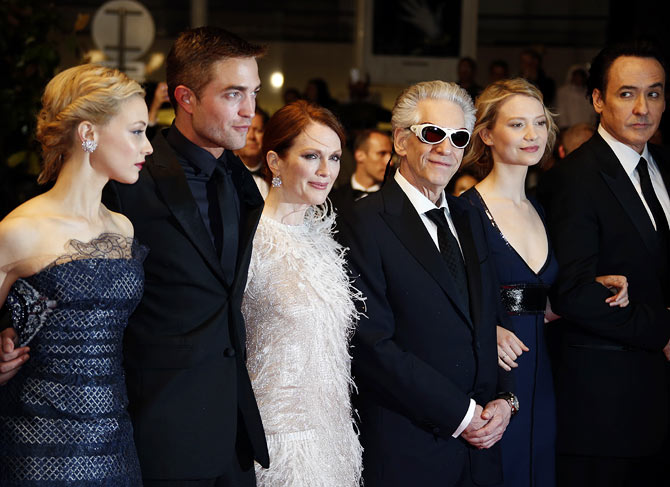

The other two top awards were for best performances by Timothy Spall as Turner in Ken Loach's film of the same name, about the great English painter, and to Julianne Moore in the David Cronenberg opus Maps to the Stars, a sardonic look at Hollywood and its stellar antics.

The Best Director award went to to Bennett Miller for Foxcatcher.

A wrestling epic, the film is gripping in parts, winning boos in others.

The Prix du Jury award was shared by Xavier Dolan for Mommy and Adieu au Langage (Good bye to Language) from the great Jean-Luc Godard, ideologue of the New Wave in cinema in the 1960s.

The Grand Prix award went to Les Meraviglie (The Wonders), directed by Alice Rohrwacher.

To them, goes the right of wearing a sprig of palm leaves, insignia of the festival, on all their publicity, something that converts into audience dollars.

Cinema's finest

For over 10 days, this town dozing on the Mediterranean becomes the centre of the world for cinema.

Four thousand media persons, a figure that tells its own tale, gravitate there.

This year, 1,800 films were submitted for consideration, out of which only 49 were chosen.

From a sieve so exacting, only the best could emerge.

But what is 'best'?

That word goes with another.

Controversy.

And this is the intriguing feature of this festival. The boos of one year become bravos down the line.

That's the trend-setting, opinion-forming power of this single festival.

Change of guard

That's what may have nudged prizes towards Mommy and the salute to Godard.

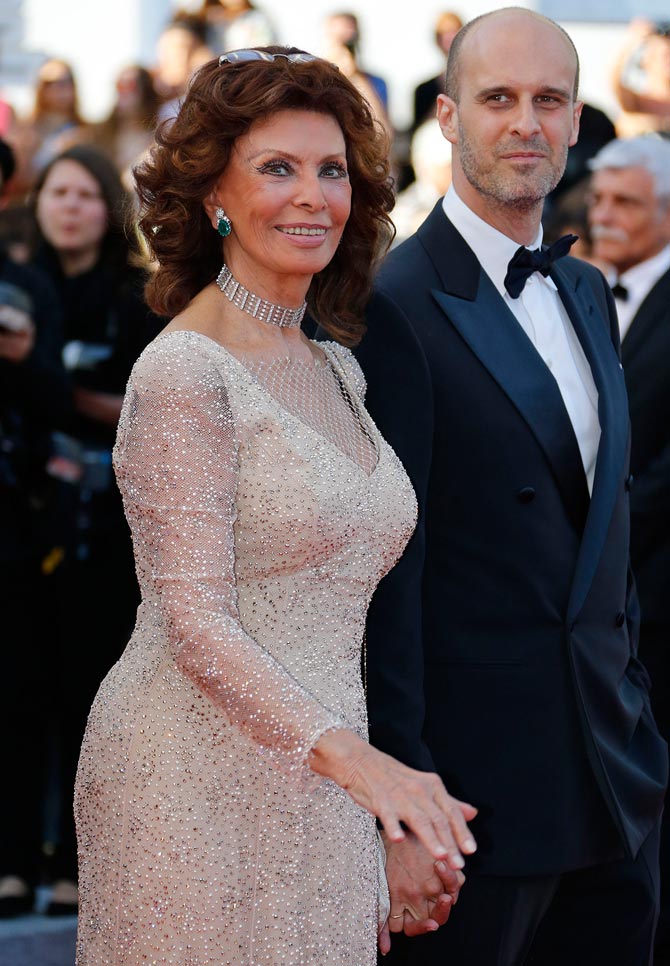

While on the subject of respect and acknowledgement, Sofia Loren (Festival Guest of Honour) was invited amid thunderous applause to give away the Best Actress award.

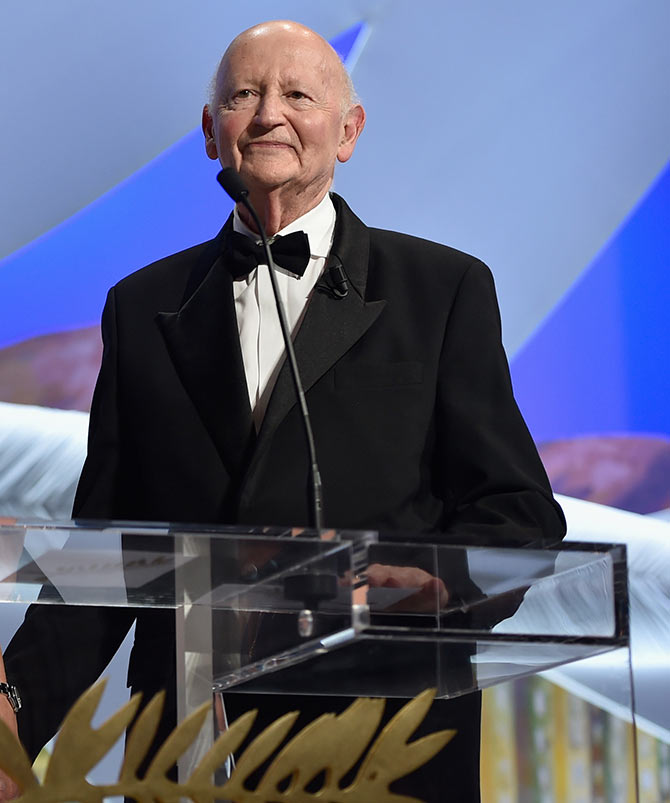

Gilles Jacob, who has run the Cannes festival for 30 years, laid down formal office this year.

He has inspired it to its current apex in world cinema and (most difficult of all achievements) picked a worthy successor in Thierry Fremaux.

Jacob was given time at the microphone at the award-giving ceremony and spoke for three minutes.

He lauded innovation and the creative spirit.

Then he walked off slowly, suddenly an old man waving goodbye.

Inexplicable also-rans

Almost as stirring as the awards and who gets them is the matter of hopes abruptly scotched.

Sissako's Timbuktu has been inexplicably ignored in the prize list.

It is a finely conceived and enacted film set in a stunning Sahara location.

It tells of fundamentalist terror invading a land of open and tolerant Islam.

Timbuktu proposes no solutions, only leaving you a kaleidoscope of images that may be the start of understanding.

An also-ran, mysteriously so, was Ken Loach's Jimmy's Hall, based on the life of Jimmy Gralton, an Irish patriot in Ireland's struggle against the British in the 1920s.

The hall in the title was built by a village community and became a place of song, dance and fun for young people.

But in the eyes of the establishment and the Church it is a hotbed of progressive and 'communist' ideas.

The film has all the markings of another splendid addition to the Loach cine-file -- engrossing screenplay, casting, depiction of landscape, empathetic direction and pacing yet passed over by the jury.

India: valued, applauded but...

India had an entry in two major sections of the 67th festival this year -- Kanu Behl's Titli in Un Certain Regard and Gitanjali Rao's animated film True Love Story.

Titli, according to an insider, made it to the last four in contention for the Camera d’Or.

This is the award for the best first film viewed in Un Certain Regard, Critics' Week and the Director's Fortnight, a challenging field.

Titli wants to break from his criminal brothers and his sleazy east Delhi settlement, is 'settled' in an arranged marriage and finds an ally and true love in his wife.

Christian Jeune, Cannes' Director, Films calls it "nearly a thriller with something to say."

Gitanjali Rao has made a lovely film in which, as usual, she does everything: animation, editing, music, the lot.

This is her third appearance in Cannes.

The first was in 2008, when she won the award in Critics' Week with an animated short Printed Rainbow.

In 2013, she returned to the same section but as a jury member.

Her latest is a kaleidoscopic take on Bollywood's impact on street life.

Cannes: More than just awards

Gilles Jacob's lifetime obsession is cinema.

In his time, the festival has grown beyond the main Competition for best film to Un Certain Regard -- Jacob who coined the term believes it is untransalateable -- International Critics' Week, Directors' Fortnight, Not-in-competition, Midnight, Beach and Special Screenings and a Short Films Competition.

In addition, there is the Cinefondation section, devoted to student film and Cannes Classics.

The last named was inaugurated six years ago with a screening of Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali.

The section screens finely restored films from all over the world and is patronised by the Martin Scorsese Film Foundation.

Of special interest to cinema in countries where it is still a developing art form is La Fabrique des Cinemas du Monde (Workplace of Cinemas of the World).

It is financed by the French government.

Its patron this year is the Brazilian director Walter Salles.

He meets each candidate to discuss their scripts.

Prospective filmmakers have the opportunity to meet producers one-on-one to explore co-production opportunities.

Etc'estfini

Onstage at the start of the Un Certain Regard closing ceremony, festival head Thierry Fremaux spread his arms wide.

"Et c'estfini," he said.

It is true of yet another Cannes.

Behind the fortunes lavished by beautiful people on their choreographed moments on the Red Carpet, the yachts in the bay (If you ask the price, you can't afford it), the partying known to have bankrupted firms -- some underlying forces surfaced.

Mid-festival, crowds paraded past the Palais with a shout of slogans.

'No more austerity! Enough is enough!'

And the cry of the lone vendor amid the hullaballoo at the main entrance to the Palais fell into some sort of place.

'Liberation,' he has called every morning, selling the revered leftist daily.

On Monday, the problems of pro and anti-austerity and of the wobbly euro will return to their normal hot focus in the media and educated conversation.

But for 11 days, it has been dreams, hopes and magic, the stuff of which cinema is made.