| « Back to article | Print this article |

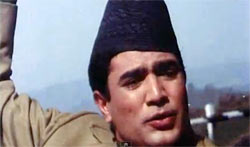

Rajesh Khanna's demise marks the passing of a gentler, more romantic era. For today's generation, bred on cinematic blood, gore and violence, it sounds a warning bell, says Sheela Bhatt.

Rajesh Khanna's demise marks the passing of a gentler, more romantic era. For today's generation, bred on cinematic blood, gore and violence, it sounds a warning bell, says Sheela Bhatt.Many of us who are in their late forties and fifties today mourn the passing of an iconic superstar, but we are not prepared to write his obituary. You don't put a full-stop to your romantic past.

Those of you who flock to see Singham may not appreciate the beautiful emotions that flooded our hearts when we saw a blushing Sharmila Tagore at the window of a moving train, stealing coy glances at a debonair Rajesh Khanna, driving alongside leisurely in a jeep. The fact that he was singing Mere sapno ki rani kab aayegi tu, with an irresistible smile and that unforgettable twinkle in his eye, only made our hearts beat faster.

If you who were in college in the seventies, and had happily bunked class to watch, or re-watch, the latest Rajesh Khanna blockbuster, you will know exactly what I mean.

To enter the theatre to watch a Rajesh Khanna film was to enter an incredibly romantic world. As we sat in the dark and saw him tell Sharmila in Amar Prem, "Pushpa, mujhse yeh aansu nahin dekhe jate hai. I hate tears," our eyes would moisten, and our heartbeats would quicken.

So many of us wanted to marry him.

There were frequent reports in the newspapers of teenagers writing letters to Rajesh Khanna with their blood and not knowing how to send it across.

That hero, who walked in so easily into our tender young hearts from the large screen of the movie theatre was so romantic, so fulsome and so 'dreamy' that leaving that illusory world to return to reality was invariably depressing.

Millions of lovelorn hearts shattered across India when the superstar married Dimple Kapadia but, in a strange way, it reinforced our impression of Rajesh Khanna as the ultimate romantic. We continued to hide his photograph from Andaz in our text books.

That one picture carried such magic that our youthful lives got a well-deserved break from the problems that were part and parcel of becoming an adult. Three cheers to that photo, where Rajesh Khanna peeped over his sunglasses with a mischievous smile on his lips and romance in his eyes. None of us were able to resist him.

Rajesh Khanna was born to woo women!

In today's world, where films like Shanghai rule, it is difficult to explain the innocence that was woven into the romance of Hindi films then. Tragically, innocence has become an abuse now.

For those of us who lived through the Rajesh Khanna era, it is astounding to see teenagers drooling over the bloody, gory violence displayed in the new genre of Hindi films. At their age, we were thrilled to see Rajesh Khanna flirt with Sharmila Tagore or Hema Malini or Mumtaz.

I recently saw the movie Gangs of Wasseypur at the PVR cinema in Saket, New Delhi. The audience, which was overwhelmingly young, was cheering and applauding the dialogues, which were outright anti-women and full of ethnic abuses.

In the early part of the film, a powerful politician ridicules a weaker character and the watching public applauds his abusive statements. The humiliation of the weak did not seem to touch a discordant chord in the viewer.

My generation is a product of the Rajesh Khanna era. We don't applaud the 'jungle raj' even though it exists around us.

Violence is, admittedly a part of human nature, but how can it be cool or sexy or normal in the way that is depicted in recent Hindi films that have grossed Rs 100 crore and more?

How can you appreciate abuses that demean your mother and sister?

Our heart and souls ached when, as youngsters, we saw Rajesh Khanna's heart-breaking dependence on Waheeda Rahman in Khamoshi or Sharmila Tagore's silent agony, caused by her love for Rajesh Khanna, in Safar.

For someone used to that kind of cinema, it was stunning to see Gangs of Wasseypur. The intelligent but cunning use of violence in the film is frightening. How can you package violence for mass exhibition and make it appealing enough to earn applause in darkened theatres?

I do agree that the excess of sweet nothings that personified the romantic era of Hindi films needed a strong dose of realism. That is why it did not come as a surprise when the angry young man, in the form of Amitabh Bachchan, arose to combat the excessive romanticism that Rajesh Khanna excelled in.

In some corner of Mumbai, the writer duo of Javed Akhtar and Salim Khan must have hated Hindi cinema's unreal world of romance; they plotted their revenge by creating Inspector Vijay.

As India changed, corruption increased; the black money-backed economy flourished and the chasm between the poor and rich became deeper and wider than ever before. Injustice and suffering increased as wealth was increasingly concentrated in a few hands.

Sooner or later, this angst was going to be reflected in the movies.

But today's genre of Hindi films package violence, cynicism and unreal depiction of realism under the garb of realism. A very dabbang ploy to make money; a bilkul rowdy act, I'd say!

The overtly sexy, earthy and tight scripts of the new Gangs of Bollywood are nothing but a ploy to mint crores through excellent marketing of violence.

If you watch Shanghai, Gangs of Wasseypur and other films in this genre, you will become insensitive to violence. You will stop feeling stunned at the emotions, or greed, that leads us to kill fellow humans. Instead, when someone is killed, you will clap.

In the Rajesh Khanna era, you saw films for the sheer joy of romance. If you wanted a dose of reality, you saw films by Shyam Benegal or regional films made by regional geniuses in a similar genre. That is how you understood violence and understood how to hate it.

But in Delhi's popular PVR theatre, the young crowd was applauding the blood and the violent language that assaulted them from the screen.

In a land that boasts of an epic romance like Kalidas's Meghdoot, sensual, subtle romance does not come as a surprise.

When you are young, when your heart and mind are tender and you look forward to the beautiful unfolding of your life, why would you want to see a gruesome scene where a havaldar (policeman) goes to the town dumpyard to find the fingers of a murdered man?

The havaldar lifts the human fingers but is not allowed to collect it as evidence by the local mafia leader. When your bones are yet to acquire critical mass, why see so much blood, folks?

Nobody is arguing that realism, and the depiction of India's unsavoury underbelly, should not be recorded in the movies at a time when the country is proving itself insensitive to injustice, poverty and exploitation of all kinds of minorities. But don't let this new breed of marketeers make a fool of you by selling violence of the mafia and the buffoonery of dabbangs in exchange for a ticket that costs anywhere between Rs 300-Rs 500!

Who doesn't need the romance of Amar Prem, or the celebration of eternal life seen in Anand?

Let's bring back the Rajesh Khanna era; please, don't write his obituary just yet!