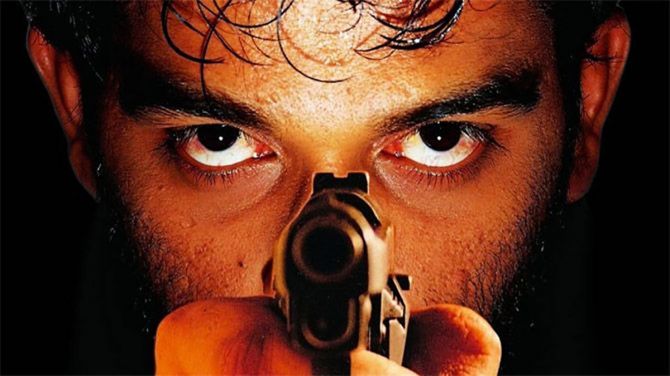

While Satya's pleasures are palpable -- among them the poetry of the coarse language, the mercifully rough-hewn texture, the oh-so-familiar underdog story -- these pleasures hit you at a completely different speed.

The movie is charged with a sense of discovery, and every shot is a cornucopia of details existing independent of the main story. It's touching, notes Sreehari Nair.

Among the underhand pleasures of revisiting Satya after many years is the pleasure of hearing the word 'Khajwa.'

Khajwa was big in the 1990s but has fallen out of favour of late. To this day I don't know what the word means, except that it seems to hint at someone who's grievously irritating, someone capable of causing a nasty itch.

Back in 1998, Rajesh Kadam used to be hung up on Khajwa. Kadam was our colony's foul-mouthed Socrates. Back in 1998, I remember him telling us colony kids about Satya.

We were seated on the flag hoisting podium as Kadam stood on tiptoes. He was informing, provoking, entertaining, and snowing us.

He was quite visibly blown away by the movie and by Manoj Bajpayee's Bhiku Mhatre.

Most of us hadn't heard of the actor, so Kadam had to remind us Khajwas that Bajpayee was the bespectacled smoothie from Swabhimaan.

"Is he any good as the underworld don?"

"Oh, it's a faadu performance," Kadam had decreed, exhaling a plume of Charminar smoke, which we accepted like a benediction from above.

This scrap of anecdote, although casual and juvenile, is suggestive of a larger fact that has been lost in the mists of time.

When Ram Gopal Varma's Satya was first released, its influence was felt much beyond the posh rows of cinephiles.

It was as though the voice of the people had finally made it to the theatres. The movie seemed to satisfy the need of a general viewing public that had been waiting for something like it but had no way of articulating that need.

And so, while encomiums by Khalid Mohamed and Shobhaa De happened on the side, Satya was just as embraced by the unpretentious and the unpolished, the crude and the vulgar, those commoners of the city who were glad to see the poetic insanities of their hearths, of their streets, evoked on celluloid minus the usual mainstream Hindi cinema flab.

Ashfaqulla Pathan, our school's affable hoodie, summed up the appeal of the movie thus: "It's nothing like an Akshay Kumar pikchar. There's no dishoom-dishoom, no andhadhun golibari. In Satya, it doesn't matter how big or small a character is. One bullet is all it takes."

I have no idea how Pathan had managed to watch the movie in a theatre given his tender age.

I myself watched it a good two years later on Star Plus at 11 pm. To me it had all the glamour of 'great smut,' and I watched shrouded in a bed-sheet with my mouth agape.

These were the memories, reflections and lamentations that rushed through my head as I sat down to experience Satya for the first time on the big screen.

The shroud was off, but the gape remained, as did the question: How did Ram Gopal Varma do it?

A people's movie that's also a groundbreaking work of art is no mean feat. How did he pull it off?

I went in with the misplaced air of an aesthetic investigator, and here's what I nosed out.

While Satya's pleasures are palpable -- among them the poetry of the coarse language, the mercifully rough-hewn texture, the oh-so-familiar underdog story -- these pleasures hit you at a completely different speed.

Varma had been preparing us for it, and just like that he makes his biggest leap. He cashes the cheque he had written at the time of Siva and signed at the time of Rangeela: Yes, Satya is as much a filmed essay as it is a fictional narrative.

The turn-ons are there for your taking, but look closely and 'life' peeks out of virtually every shot.

The rain never seems to stop asserting its patter. Some self-commemorating fella smokes away at the edge of a frame that has Bhiku planning his next murder.

A little girl plays hopscotch in a hallway that Satya crosses, unkempt and unsure.

A street urchin abruptly bisects Vidya and Satya on the footpath as if to say, "Keep your distance, lovebirds."

The movie is charged with a sense of discovery, and every shot is a cornucopia of details existing independent of the main story. It's touching.

I sobbed a little just surveying those TV antennas and Sintex water tanks and groaning scooters, relics of an era that had vanished right before my eyes.

Yet none of it feels 'planted,' and it's all delivered to you light-on-the-feet, hot-off-the-pan.

Bhiku Mhatre, walking over a pile of gravel, loses his balance as he ribs Satya about Vidya. In a typical Hindi movie of the nineties, that loss of balance would not have made it to the final cut.

When Jagga, an equal offender of people and of the Hindi language, is shot in a dance bar, he slumps over like Sollozzo in The Godfather.

His heart stops beating, but all around him the beats continue unabated: It's that nervous number, Mujhe Pyar Hua Allah Miya, straining towards its jittery crescendo.

These layers and triumphs of staging come out of Varma's expressive need for them. This is why they are so emotionally affecting.

When Varma is at his best, he's a master of technique and not a slave to it.

Take, for instance, the episodic structure of Satya, which allows him to hop from one moment of ecstasy to the next while always staying close to his natural curiosity.

The bitterest thing you could say about the man is that he's a sellout with a vision. He wants to give his viewer all the highs of a popular entertainer even as he expands the possibilities of the medium.

Watching it again after all these years, I began to wonder if Satya was conceived as an action movie about a bunch of characters who emerge from the crowd and eventually dissipate into the crowd.

As a gangster who loses his mojo in the din of a public place and ends up lifeless on the Mahim Foot Over Bridge, I know a certain Guru Narayan would agree.

So how did Varma do it?

If insider accounts are to be believed, a string of newspaper stories had released his imagination, following which he raised the dough, assembled a team of fresh faces and untested technicians, and inspired them to come locate an enduring piece of sculpture inside an innocuous slab of marble.

That is to say, they learnt how to make Satya as they were making it.

And since this gonzo approach could have gone either way, you've got to give it to Varma -- what an act of confidence, what an act of folly!

More than anything, Satya is the work of an artist at a specific time in his life.

It bespeaks a perfect union of the artist's intuitions and his physical response to those intuitions.

I am not being flip when I say that there's something 'glandular' about the movie.

And it feels like a different movie when you come to it older, when you come to it with your ideals ageing and your hormonal infusions not what they used to be.

It's then that you observe the deft touches in Manoj Bajpayee's career-making, epoch-making performance.

How he sits obediently beside Bhau as he's served the elder brother's injunction.

How he swallows his laughter while answering an important phone call.

How he leaps from anger to a sudden epileptic bop. It's only this time that I saw the delicate intelligence that runs through his harsh falsetto.

For a spear carrier like Bhiku Mhatre, 'loose cannon' is also an image-keeping exercise, a role he has to play every day.

And Bajpayee convinces us that Mhatre's theatre is part of his core competence.

It feels weird to say this, but the movie is respectful of the dignity of every profession, and it has an eye for those grace notes that make each of those professions special.

I love that moment of Paresh Rawal's Amod Shukla and Aditya Srivastav's Khandilkar patiently waiting for the Commissioner's tea-serving wife to leave the room so that they can get back to discussing gangsters once again.

Varma's interest in sociology is evident in the way he designs certain walk-on parts.

Neeraj Vora appears as a music director to whom 'leching' comes as naturally as 'rhythm.' While in the throes of an indecent proposal, he finds the perfect tune.

This three-scene character is a masterpiece of comic skullduggery, and it made me long for Vora, that cleft-chinned genius gone too soon.

In Satya, every son of a gun, however fleeting his appearance, throws echoes upon your soul.

Take Govind Namdeo's Bhau Thakurdas Jhawle, an incarnation of that old-world adage: "I'm a conquistador because my mommy loved me."

You can sense that this cautious-eyed man has never been turned down. You can sense the spoilt child aspect of him in how he responds to contempt, how he flings his garland and parts his curtains.

These performances are immediately inviting, but there are also those that foreshadow acting styles yet to come.

Sanjay Mishra's contract killer uses intonations that Nawazuddin would later make his own.

Shefali Shah's Mrs. Mhatre seems to be on a permanent quest to out-speak everyone else, and this feels like a minor rebellion, the protest of a gifted actress demanding her close-ups, something to capture her time-stopping stares.

Kallu Mama, who scowls every time a murder is planned, would have been a killjoy but for the actor playing him.

Saurabh Shukla makes us empathise with Mama's efforts to maintain the sanity of 'number-crunching,' even as bodies pile up all around him.

Shukla gives a supremely fluid performance while being bolted to his chair almost the whole time.

Though a Pankaj Tripathi signature in 2025, this was a real mould-breaker in 1998.

Everyone in the movie is rooted, one way or the other, everyone except the title character, who is introduced as a man from nowhere.

And as I made my way out of the theatre, I thought about the bearded fatalist, described over the years as silent, dark, brooding, a mere plot device, and just a stand-in for Ram Gopal Varma.

It struck me this time how impeccably balanced Chakravarthy's Satya is as a conception.

Suppose he were any more exuberant or more of a weenie, the entire facade of the movie would have crumbled.

Varma sets him up like a gun-for-hire from those old Westerns and reveals him to be as defenceless as you and me.

A specialist in throwaway quips, a cipher in the true sense of the term, he comes alive when his story intersects with the story of others.

He grows in stature when seen through Bhiku Mhatre's bright unsteady eyes and when Vidya gazes at him Bambi-like.

To Bhiku, Satya is a personification of the 'speak softly and carry a big stick' ideology, and Vidya is drawn to his part-kindly, part-dangerous stares.

There's some truth to RGV's claim that he makes movies from the gut, but the finest creative choices in his movies still point to the presence of heart and soul.

Varma's presentation of Urmila is a prime example of this. It's a testimony to the artist-muse relationship they once shared: He lets the camera feast on her alabaster face, and by and by it becomes the face of the classic innocent bystander.

Her confusions seem to make her more beautiful, so that in the closing sequences we feel her terrors with greater intensity.

Come to think of it, this is the story of a man who's being tugged in two different directions.

Here's a man faced with the impossible task of choosing between Bhiku Mhatre's rakish charms and Vidya's gentle, seductive looks.

And in his inability to make up his mind, Satya anticipates the end of the Mumbai underworld.

The irony is that Varma had set out to make a fast-paced movie about a bloody milieu.

Instead, he ended up giving us a view of that milieu that was as intimate as it was startling.

He made us care about the very antisocial menaces that the newspapers were railing against.

This is why Varma's great act of folly continues to sting and sing. The movie is an object lesson in how an artist pursues timeliness only to make something timeless.

The Mumbai underworld may be long gone, but Satya lives on.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025