Friendships are not merely severed, but built over scuffles.

And just about anything can stir things up -- a long-standing feud, a pointless stare, a disrupted moral stance, a fist that ricochets off a face and smacks another face in the near vicinity, observes Sreehari Nair.

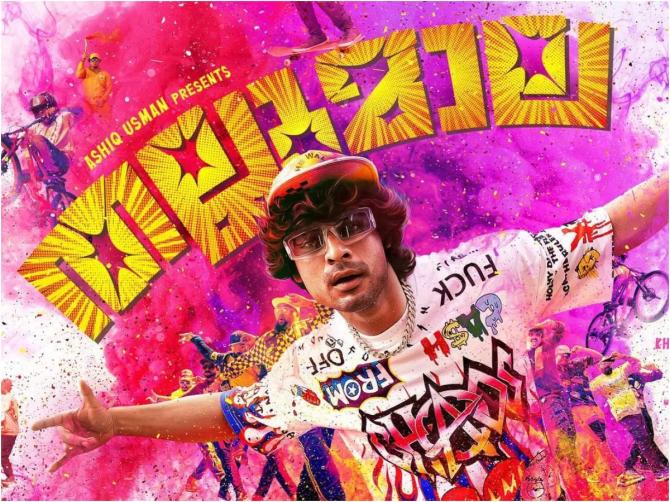

The makers of Thallumaala were dead set on marketing it as an Adi Padam -- the Malayalam term for a film that wants to be nothing more than an honest-to-God variation on the Action Film genre.

When you want to show pure Action on screen, but have more imagination than to simply blow things up using expensive VFX, and have the good taste to not confuse torture porn with Action, you get your actors to duke it out mano-a-mano.

Slaps, Punches, Kicks, Head-butts, Elbow Strikes, Nutcracker Chokes -- the more diverse the set of combat moves that make up an Adi Padam, the more wholesome the experience.

Thallumaala's Director Khalid Rahman and its chief writer Muhsin Parari knew that if they slot their film in the right 'category' the footfalls are sure to happen, and the film's box numbers thus far prove that their instincts were on point.

Broadly speaking, Thallumaala tells the story of two gangs -- the Wazim Gang headlined by Tovino Thomas and the Reji Mathew Gang led by Shine Tom Chacko -- who embody different grades of toughness but are bound by their love for a good fight.

The film delivers on the promise laid out by its makers by having the two gangs fight each other, and others like them.

So they fight outside a mosque, on a boulevard, inside movie theatres and wedding halls and grungy neon-lit garages, and the original promise is remade with bodies and upholstery and teeth flying, holy water splashing, blood streaming down defiant faces, so that we get a cornucopia of dance-fight-physical comedy, something that Buster Keaton, Mike Tyson, and a whirling Dervish, working in concert, might have dreamt up.

Thallumaala's kinetic look is the result of a close collaboration between Cinematographer Jimshi Khalid and Editor Nishadh Yusuf, who have put together a film that outwardly at least seems tailor-made for the Instagram Reel generation.

I must warn you, however, that this is an exhilarating-yet-exhausting picture, and sitting through it is like speed-reading a comic-book.

Your eyes come up against lurid colours, graffiti backgrounds, speech and thought balloons, images that detach themselves from one scene and become the vantage for the subsequent scene, and Chapter Titles sizzling with puns.

The dialogues have a woozy wit (they are the sort of lines you might say after you have drained yourself of feeling), and as a hat-tip to Yashraj Mukhate perhaps, the characters suffer from frequent bouts of onomatomania, in that they repeatedly get stuck on a word or a phrase or a name and turn it into a song.

While on the subject, did I tell you Thallumaala is also a musical?

Viewing it through these specific lenses, Khalid Rahman's film is a no holds barred celebration of a shallow and materialistic way of life -- and it's great fun for that very reason.

The characters talk and behave as if to keep their social media image, and there's a lot of astuteness in the casting of Kalyani Priyadarshan as Fathima Beevi, a glassy-eyed Goddess who benefits from the actress' slugged look and her cover-girl face, and who charms and later dumps Tovino's Wazim with the same degree of offhandedness.

All this is good, but Thallumaala also operates at another level, a less superficial level, and this was probably the level at which Muhsin Parari had conceived the project.

There's a famous story about In Search of Lost Time, how Proust had written his great book on memory, after wanting to initially do a study on stained glass windows.

Something similar may have happened here.

Parari has composed his bubble-gum tale out of notes and musings and commentaries about the very nature of fights that break out randomly, grow by slow accretion of ego, and end with a sputter.

The men in Thallumaala live for the opportunity to get down and dirty.

This is how they test each other and themselves.

Friendships are not merely severed but built over scuffles. And just about anything can stir things up -- a long-standing feud, a pointless stare, a disrupted moral stance, a fist that ricochets off a face and smacks another face in the near vicinity.

Each brawler remembers every detail of each fight he has been a part of, and each fight is recorded in his head as a separate journal entry.

There are those memorable coming-of-age fights decorated with graduation cap tassels and indexed according to the special moves that had sealed those particular fights.

Then, there are the fights lost, the butt-slaps and pasting received during which remain burned in the loser's memory, the scores for which until settled continue to haunt his waking dreams.

The aspiration to make philosophical inquiries into a seemingly frivolous social phenomenon runs through Thallumaala, and this is what elevates the film from the rank of a mere Adi Padam. And even as an Adi Padam, I believe this is a more honourable film than, say, a film by Vetrimaaran, in which scene after scene of ultra-violence is justified by citing some social statistics or sensationalist newspaper report.

Muhsin Parari may have grown up loving those brawl-fests of his childhood, he may have even had his share of scuffles, but he is now clearly on the side of the mothers in this movie, the ones who wield the power to stop fights by offering the brawling numskulls a few servings of their special Nei Choru and Chicken Curry. And seen from this perspective, Thallumaala is at once a jamboree and send-up of conventional action pictures; it delivers the wham-bam pleasures expected of it, but without hinging on the simple-minded Victor Versus Vanquished formula.

The actors understand exactly what the film is going for.

The performances on the one hand seem to us acts of self-commemoration, and yet, we can sense the self-effacing air that hangs above each of the characters.

Shine Tom Chacko, that actory actor, uses his penchant for word-garbling and word-swallowing as well as many of his own neuroses to bring Sub Inspector Reji Mathew alive for us.

Mathew is a man making peace with the fact that his wayward brawling days are over, that whatever violence there is in him must now be put at the service of the state machinery. And the members of the Reji Mathew Gang are all awake to the changing tide.

They know they are not adolescents anymore, cannot afford to behave like adolescents, and so, when they see a set of 'not fully-formed' greenhorns trying to be all tough, a completely normal desire to poke at their tender tendons and deflate their fragile psyches begins to take shape within the old boys club.

If the actors who make up the Reji Mathew Gang are required to be true to the script's psychological acuities, then the actors who constitute the Wazim Gang are expected to respond wholeheartedly to the film's never-flagging energy.

In this amusement park of a movie, Tovino, Lukman Avaran, Swathi Das Prabhu, Adhri Joe, and Austin Dan, are responsible for two things: they have to provide the park with its theme, and also have to demonstrate what it means to be flung into a series of wild rides.

Acting, in this movie, is not about 'immersing yourself in a character', it's about helping to complete the movie's stylistic universe.

For instance, when Tovino's Wazim is treated to a round of rapidly changing hairstyles, he's not so much 'behaving in character', as being a generic astounded kid who cannot believe that he's having this out-of-body experience. And yet, Tovino manages to trace a real person out of the crayon sketch.

He gives you a hint as to how the mental makeup of Wazim changes as he ages from 18 to 24, and that is a far more difficult feat to pull off than a straight biography of a man's entire adult life.

Wazim matures by developing in sequence a wide-eyed look, a wise-but-madly-in-love look, a break-up look, and in the tense pre-climax sequence, one that happens on the night before his wedding, where the two gangs get down to play a game of touching-but-not-touching, our man looks like a spring that is being slowly wound up with every passing second, wound up and all ready to go 'boing!'

Thallumaala is set in Ponnani, but has been shot extensively in Thallassery. We are talking Malabar, Kerala, where people speak in a tongue significantly different from the one employed in Central Travancore (which is where I come from).

Malabar may have produced many literary sons and daughters, but none quite like Muhsin Parari -- who is steeped in the specific rhythms of the region while possessing at the same time a talent for finding pop in the most unexpected places.

Since his breakout hit, Native Bapa (which felt like Eminem taking James Baldwin out for a date), Parari has given us some of the finest and most original mugshots of sweaty Malabarians -- and these include, among others, football fanatics, marriage brokers, rickshaw drivers, and ATM security guards.

Even stock characters, such as the worried mother or the alcoholic genius, when imbued with Parari's sensibility -- and it is a comic sensibility -- attain a unique cast of mind.

But there's also a grain of protest that runs through all of Muhsin Parari's works.

The protest isn't necessarily directed at a political party, or a group of people, but at a phenomenon that has come about following the World Trade Center Attacks of 2001.

The result of watching acts of Islamic terrorism being broadcast live on television is that even the best and most broadminded of us, today, love Muslims but only until we are sure that they don't take their religion seriously. (I don't know if it's right to call this phenomenon Islamophobia, because it definitely is a lot more complicated than that).

Parari's way of protesting against this phenomenon is to fill his films with orthodox Muslims, who are otherwise viewed only in a political context, and showing us the beauty, the banality, the poetry, and the humour in their everyday lives. And as he gives us these characters, and reveals the minutiae of their existence, he seems to be asking us: 'Do these images stress you out?' It's a question all right, but it makes enough of a statement.

On the face of it, Parari the pop artist takes over Thallumaala.

He has a simple story to tell, but proceeds to tell it with a certain attitude: Breaking the story down, mixing the bits so that chronology becomes a non-issue, advancing the narrative without any intimation, inserting flashbacks, then flashbacks within flashbacks, and keeping things always interesting, always moving, so that by the time you make total sense of what's happening on screen you may be left breathless and somewhat reluctant to blink.

And when in such a pop environment Parari's characters invoke Allah, and moreover, in situations where we don't expect such invocations, Parari's question ('Does it stress you out?') seems to ring louder than before. This is one of the films of the year.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025