It is the most potent symbol of India's soft power -- more perhaps than the IT industry and our managerial skill, notes Vanita Kohli-Khandekar.

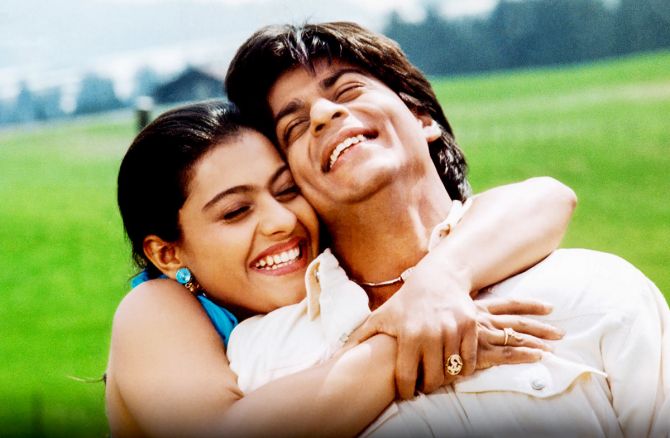

Aditya Chopra's Dilwale Dulhania Le Jaayenge or DDLJ (1995) is among the iconic films of the world.

Raj and Simran's love story is inextricably linked to (leading man) Shah Rukh Khan's rise, to a liberalising India discovering the world and yet clinging on to things Indian -- the warmth of family, weddings and the quirks of being desi.

DDLJ is one of the most successful films both within and outside of India.

Last month, on the 25th anniversary of its release, Mark Williams, director of destination marketing, Heart of London Business Alliance, announced that a bronze statue of Khan and Kajol as Raj and Simran will be unveiled at London's Leicester Square in Spring 2021.

The statue, depicting a scene shot in Leicester Square, will join nine others like Harry Potter, Mary Poppins and Mr Bean.

This is such a wonderful way of honouring and celebrating the joy and prosperity (through film tourism and ticket sales) the film has brought to the UK.

It is also in stark contrast to the dishonour and the slander the Rs 19,100 crore (Rs 191 billion) Indian film industry faces and the muck that is thrown at it by rogue news broadcasters and vituperative trolls on social media.

For almost six months now, the Indian film industry has been painted as a festering cauldron of drug addicts, deviants and fake-depressives.

This piece is not about India's national shame, its news broadcasting industry.

It is about its pride -- the film industry.

It is for four simple reasons, often cited by this column, one of the best things to come out of the country.

One, it is phenomenally resilient.

After the breakup of the studio system in the 1950s, many committees asked for industry status for films but no one paid attention till 2000.

It has had no institutional support, no protection and no subsidies.

Yet Indian cinema has stood its ground for over 100 years even as most of the world has been swamped by Hollywood.

Over 85 per cent of the industry's revenue comes from Indian films.

Roughly one-fourth of all television viewing, over 70 per cent all music sold and a chunk of OTT viewing is films.

Two, it is the most potent symbol of India's soft power -- more perhaps than the IT industry and our managerial skill.

When 3 Idiots and Dangal became hits in China, the worried Chinese called a meeting to understand their lack of creative soft power.

When A R Rahman, (the late) Irrfan, Aishwarya Rai-Bachchan, Priyanka Chopra, Khan among others win an award, perform at the Oscars, speak at Davos or TED Talks, they do India proud.

Three, its critical role in the future.

As the boundaries between technology, media, telecom and retail collapse, a new ecosystem with Google, Facebook, Amazon, Disney and Apple is emerging.

They are in a frenetic bid for scale and audiences across geographies, technologies, genres, even across industries.

In this new ecosystem, India can gain and come out tops not with its media or tech firms but with its creative ones.

On YouTube, the world's largest streaming platform, T-Series, an Indian music firm, has the most watched channel.

Since its entry in 2016, Netflix has announced over 60 titles to be sourced from India, one of its largest markets for sourcing.

These are streamed to 193 million subscribers in 190 countries showcasing Indian stories to the world.

Two-thirds of the viewing of Sacred Games happened outside of India; over 27 million households across the world, including in Latin America, viewed Mighty Little Bheem.

The numbers are different, but this holds true for Amazon Prime Video as well.

Four, Indian cinema employs 7 million people directly and indirectly across production, retail and other areas.

Yet almost all governments treat the film industry as the 'dumb blonde' of the economy.

You ask it to shake a leg at events to raise money for some state purpose, but otherwise you tax it to the sky, blame it for social problems and never stand up for its creative freedom.

Why is it that an industry that tells wonderful stories like Piku, Masaan, Uyare or Palasa is so bad at defending itself every time there is an attack, on a film, a person or on the entire fraternity?

Why is it not able to showcase to the media, to the government and its audience, how it serves India? Shobu Yarlagadda, the producer of Baahubali, reckons that the industry is too fragmented, across languages, states and different interests.

That makes speaking in one voice difficult.

It is an issue the TV industry faced for years before a few large broadcasters took it upon themselves to get the Indian Broadcasting Foundation to be more active.

They got advertisers to pay up on time and took on regulators on price restrictions.

This, then, may be the IBF moment for Indian cinema.

Earlier in September, The Film and Television Producers Guild of India released a statement denouncing the relentless attacks on the film industry.

Though it does not represent all geographies, languages or parts of the ecosystem, it is a beginning.

It is time to fight back.

© 2025

© 2025