'What would a composite of Dawood, Rajan, and Arun Gawli be like?'

'What if an absconding mafia boss were to land in Mumbai tomorrow, tired from all the running, and tender his final apology to the city by narrating his story and narrating it with brutal honesty?'

Sreehari Nair watches Sacred Games.

Sacred Games is the story of a city under siege telling us how it came to be the city it is.

Handcuffed to its past and uncertain about its future, Mumbai speaks.

Using a bunch of rich, complex, unreliable characters as its medium, it speaks about that post-1980s nexus of Crime, Sex, and Power -- basically everything ungodly that gives Mumbai its pull -- and it speaks about that balm of God & Religion that soothes its every guilt.

This series, India's first Netflix Original, is adapted from what was probably the first true Mumbai Novel, a novel that aspired to cram as much of the metropolis between covers as it possibly could.

Vikram Chandra even invented an English specific to Mumbai -- and then, as a tribute to the city, he refrained from adding any word-index or footnotes (Which means, terms such as "Mausambi" and "Doodh Ki Tanki" would have registered as daily-speak to some readers and as music to the others).

Given the expanse of the book it's adapted from, the Netflix series could only have been an act of compression, and Directors Anurag Kashyap and Vikramaditya Motwane have used the incidents, gossip, and folklore in the book to craft what is essentially a race-against-time thriller.

My two-rupee theory about adapting novels to screen is that it works best when a director takes a trashy novel or a genre novel, finds something of personal value in it, and then broadens its shoulders.

Mario Puzo's The Godfather (not arguing with those who claim the book to be better) was a potboiler, a good chunk of which was dedicated to a bizarre character named Lucy Mancini and her inability to experience orgasms.

In the movie version of The Godfather, Coppola, in enlarging the scope of the story had reduced Mancini to just one of the many wedding guests whose real moment of glory came when Sonny Corleone had sex with her, standing up.

Anurag Kashyap, too, has done his share of potboiler reworking; using the journalistic nuggets in Hussain Zaidi's Black Friday as energy pills, he had given the film a narrative integrity that the text lacked.

Sacred Games, however, is not just a novel dense in details: it is also a novel with a philosophy of its own.

And in following its two stories, Kashyap and Motwane divide the beats of the book thus: Motwane takes on plot while Kashyap wrestles with philosophy.

The primary ruse of the novel concerns a tip-off that Sartaj Singh (played here by Saif Ali Khan) receives about underworld don Gaitonde (here, Nawazuddin Siddiqui) and in this series the ruse becomes the focal-point -- this is the part that Motwane tackles.

If Motwane is chasing the enclosing narrative, Kashyap has directed the narrative within the narrative, as Gaitonde -- who begins by informing Sartaj that he has 25 days to save Mumbai -- starts telling his life story, with his pride, his shames, and his God Complex running amok.

What starts out as a two-pronged tale soon becomes a tale of two directors.

And as the series progresses, Gaitonde's story becomes so overpoweringly interesting -- with Kashyap adding so many mystic, magical, touches to it -- that it dwarfs Motwane's telling of the Sartaj story.

As Motwane's characters cross rooms and hallways, Kashyap's maniacs seem to be waltzing through the pages of a pulpy history textbook at high-speed -- with marvelous things often contained in one look, a tossed away line, or dialogues uttered in passing.

Motwane does sustain tension, but when played back-to-back, Kashyap's 'fantastique segment' feels like a wild García Márquez story fighting its way out of an uncharacteristically slow Graham Greene spy novel.

Not surprisingly perhaps, Motwane's quality of feeling comes roaring out in his treatment of the Maharashtrian characters.

Jitendra Joshi as constable Katekar, with his bullet wound from 26/11 yet unhealed and his compensation yet unoffered but who still has Marathi pride up to his ears, will ensure that you'll never again look at a policeman with quite the same eyes.

And it's only when Girish Kulkarni (playing politician Bhosale) and Neeraj Kabi (playing DCP Parulkar) do their bit of 'Strategic Dribbling' in Marathi that their characters come alive.

Bhosale and Parulkar, whose relationship starts with Parulkar's indifference and ends with Parulkar having to play stooge to minister Bhosale, represent the uptight bureaucracy built on a pile of cash, lies, and bitter ironies.

And Katekar stays outside this false castle, taunting the fishes.

"And they think, only policemen accept bribes," says Katekar to the fishes, as he feeds them their worms (The writing by Smita Singh, Varun Grover, and Vasant Nath is consistently sharp without the lines ever sounding self-aware).

Though peppered with felt helplessness, what Motwane's moment-to-moment tracking of the enclosing story lacks is the kinkiness and swiftness of Kashyap's fabled storytelling -- which goes from 'Gaitonde on a Tiger-Print Bed Sheet' to his childhood in Solapur to dingy Mumbai chawls to Jungles that look almost Colombian to Garbage Dumps that scream 'Treasure!' and finally to swanky bungalows where tears flow as freely as alcohol.

Kashyap's segment, every time it's activated, goes off like a firecracker.

You can fault the man for not knowing how to conclude his stories, but what he has in spades is Film Sense.

Gaitonde's story arc has the feel of sex that's constantly pushing into the unknown, and of good jazz being created using wild improvisations; it is hallucinatory, it flows, and everything you see goes right into your head.

Contrast this with Motwane's section, where, as always with the director, there are not more than two people who show any real 'presence' in any given frame.

Kashyap's busy cameras and overlapping dialogues, his innovative way of shooting crowds, his quick cuts -- they don't judge! And in overfilling our sense of reality, he opens us up to more possibilities and thereby sharpens our sense of morality.

The crowds and the madnesses of Kashyap's Mumbai is the Mumbai that often passes by you, unmarked; Anurag Kashyap is every bit a maximalist for the minimalist that Vikramaditya Motwane is.

Motwane's effects are, if you want to call it that -- 'subdued'! His way of shooting is more methodical and his poetry is more pre-worked and there for you to 'catch.'

Working with Varun Grover, a poet of faint nudges and caresses, Motwane creates a wonderful moment where a rendition of "Main Na Bolonga; Main Na Boloongi" cuts between Saif's Sartaj Singh and his estranged wife, and then it plays out in a bar with bargirls grooving to that very song.

One man's pleasure, as they say, is another man's penance.

Saif Ali Khan's Sartaj Singh comes home to a name-board that still has his wife's name on it; she isn't around, but his identity continues to be wrapped around hers.

I have always believed that that craving to be an object of desire may have eaten into Saif Ali Khan's strengths as an actor. And so, it's reassuring to hear him being described here as a low performing, hungry-for-attention, driven-to-anxiety, overweight policeman.

But, make no mistake, a saint he still is!

This is, perhaps, where the series majorly differs from the novel. The novel had Sartaj presented as a Philip Marlowe-like character: idealistic yet cynical, and in some ways, weak before temptation -- he pummels people for money and gets into bed with freelance journalists.

In the TV series, he is all white.

This is why we feel there's little in Sartaj Singh that we can connect with, and what Khan mostly manages to convey is the resourcefulness of his character: He walks the Nirmal Lifestyle area of Mulund at nights, scouring desolate malls and unlocking parked cars.

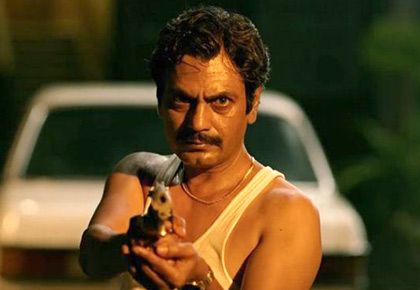

The Gaitonde character was perhaps born out of a set of hypothetical questions.

What would a composite of Dawood, Rajan, and Arun Gawli be like?

What if an absconding mafia boss were to land in Mumbai tomorrow, tired from all the running, and tender his final apology to the city by narrating his story and narrating it with brutal honesty?

Gaitonde does narrate, and in Nawazuddin's improvisations of the Don's ramblings, prepositions and sentence connectors are dropped at will and the 'essence' of the man gets expressed.

To hear Nawazuddin recite his dialogues is to discern the kind of poetry that comes with the stacking together of two unrelated sentences.

It must be tough being Nawazuddin Siddiqui, and convincing people that his brilliance isn't in playing a 'certain type', but in his ability to discover, within the most overused stereotypes, fresh reserves of tenderness.

What Nawazuddin taps into here is Vikram Chandra's original vision of Gaitonde -- Gaitonde as Mumbai: Ambitious; corrupt; charming; dreamer of dreams; defiler of dreams; teller of stories; distorter of stories.

He believes with all sincerity that this is Gaitonde's world and others merely live in it.

There are no real people, only 'characters' in his ever-expanding narrative and his job as the writer of destinies, he says, is to replace them at moments most opportune -- he is a 'replacer' and that's his justice.

At one point, he says, "I have seen my face in every person I have killed," and in that one sentence, you get how he plays his game: Right up against the face of death.

What Kashyap and Nawazuddin have created in Gaitonde is the vision of a man who cannot make love to a woman unless he's also making love to himself -- his image of himself is what drives him forward.

And yet, look at how he pulls up his pants in the middle of a smuggling transaction or has his collar buttoned up before he strides into a nightclub: His leaps never interfere with his beginnings.

Gaitonde sets the terms and others abide.

He has his way with everyone except Kukoo; who in the novel, is described as a bar-dancer who when she dances, it makes grown-up men weep -- they pay to just watch her dance and shed a few tears.

But to Gaitonde, she's Mumbai's gift to you; she is Mumbai telling you that you have arrived.

The Kukoo-Gaitonde love story which begins with a brilliantly staged scene, that has the camera looking up to her (mimicking Gaitonde's gaze) as she outlines her credentials, ends with Kukoo's ultimate subjugation as she begs for that one kiss that's never quite delivered.

The Kashyap-Nawazuddin segment takes you down an alley of bittersweet experiences that emerge from the grime, dust and filth of noble Mumbai -- and it goes about its journey at such breakneck speed that it leaves you breathless.

And when you're pulled back into Motwane's world of sophisticates -- clean-cut policemen; well-groomed R&AW officers (Radhika Apte is brilliant as a R&AW agent who's unable to locate the 'human' in a 'source'); urban gangsters -- all making the walk from Point A to Point B, without missing as much as even a tile, the pause seems eternal.

Despite the unchanging coldness in the modern story, Sacred Games is smart enough to keep itself tethered to that one theme without which, it knows, this story cannot be told: Piety.

Both the book and the series believe that we are victims of a particular brand of Piety -- which brand has become the engine we turn on to advance our fortunes and also the beast that consumes us.

We are idols or idol-worshippers and our marketing, our businesses, our social structures, our politics, and even our relationships are built on this sad reality.

Parulkar, the DCP, is buggered by the minister and in turn Parulkar buggers his juniors -- reminding them of that 'salute' that he must have and shall not do without!

The master-servant narrative is continuous in its propagation.

And during times of enormous pressure, it is this narrative that we unfailingly peddle to deceive ourselves.

Both the corrupt minister and the corrupt DCP know their sins, but Piety deludes them into believing that they are at the service of something more important, something higher and more divine.

"Jai Hind," says the minister.

"Jai Hind," says the policeman.

© 2025

© 2025