'It's a performance that puts the Bachchan hysteria to shame,' observes Sreehari Nair.

It's when the characters in Gulabo Sitabo stop fighting, that they quit breathing.

The people, in Shoojit Sircar's latest, are alive in their aggressions; and alive they are, in their bitter admirations.

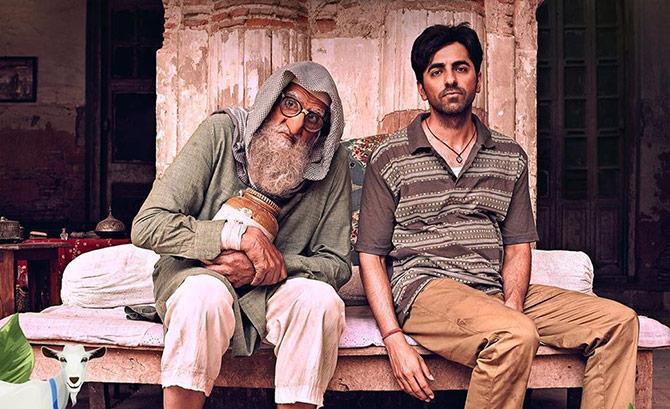

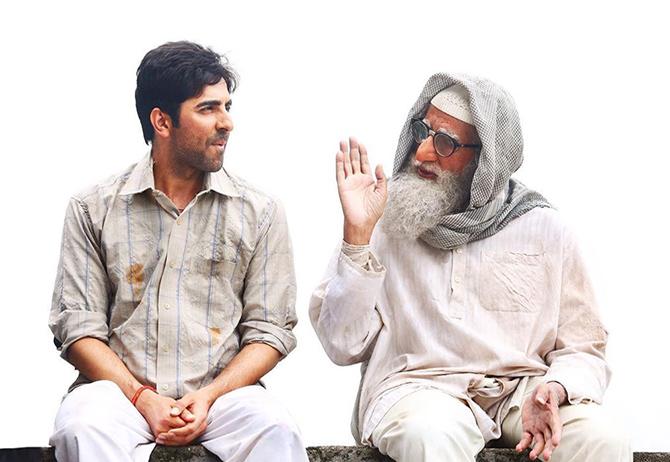

When Amitabh Bachchan's Mirza tries to trap Baankey (Ayushmann Khurrana) in a cage of chaste Lucknowi curses, Baankey pauses for a few seconds, as if to acknowledge the virtuosity of the foul tongue, and then proceeds to almost ride his motorcycle over the old man.

Realising that he was unsuccessful in putting the hex on his freeloading tenant, Mirza, hunched over and hands akimbo, declares all-out war on Baankey.

The scramble to have the final word in an argument produces its own kind of music, and it is this note that Gulabo Sitabo consistently hits.

The men and women, in this shaggy dog story, live for their verbal dodges and for their sulphurous back-and-forth. And their eyes light up every time they find just the right catchphrase to express their contempt.

Writer Juhi Chaturvedi and Director Sircar do some of their best work in the first one hour, by staying half in and half out of their characters's bickering, penny-pinching attitudes.

These are petty, grouchy people, but they are not put down for being petty and grouchy. The picture keeps you laughing because it's so nonjudgmental.

And since nothing is pushed at us, we can reach out to the subtexts and the underlying themes.

We notice, for example, that, for all the bluster and yakety-yak, this is hardly a world of memorable punchlines: as a matter of fact, it's a world where language is used to hide true feelings rather than affirm them.

The characters in Gulabo Sitabo speak so as to conceal their deepest shames, their biggest failures, and their discreet acts of immorality. And very often, that for which they can find glorious words is something already dead in their hearts.

When Mirza talks about how Baankey doesn't possess the look of a property owner, the vulture-faced 78-year-old man is, in truth, lamenting his own wilted fortunes: He's talking about the look he had always coveted, but could never have.

It isn't every day that you see grouchy individuals being treated as romantic figures but Sircar and Chaturvedi are the perfect team to devise such a treatment because of a startling contrast in their sensibilities: He's a poet, while she's extremely practical-minded. He has great feeling for beauty, while she constructs things from the ground up.

Chaturvedi seems to know her people down to their sweat glands, and their orifices. My guess is that she has a talent for seeing how someone's soul may manifest itself in a certain physical attribute.

In her mind, a person with hair sprouting out of his ears must have a very specific moral character.

Juhi Chaturvedi is sensitive to, how we converse through our exhalations and, how we let our obsession with our bodies affect our interpersonal relationships -- and here, our most elemental screenwriter, turns the first hour of Gulabo Sitabo into a celebration of chaos.

I whooped at a reviewer who found the initial sections of the film 'meandering' because that is the kind of reading that suggests you are afraid of the Indian chaos, afraid of looking at a world where histories and perspectives are in collision, and your general attitude to a work of art is, 'Let's get done with the complications, and get straight to the message, the moral point.'

But, for a good part of its running time, Gulabo Sitabo isn't interested in making the moral point; its primary intention is documenting a series of ideological battlegrounds, each of which becomes a microcosm of the Indian Experience.

The traditional puppet play, which gives the movie its title, was hoisted on the popular notion that men resolve their disputes physically while women let them dissolve into a series of squabbles.

Chaturvedi shows us that endless squabbling is something even men are capable of -- in fact, in Gulabo Sitabo(as in Kumbalangi Nights) it's the male characters who're stuck, and it's the women who're hopping about.

Guddu, Baankey's sister, has history and civics lessons on her lips, dreams in her eyes, and sex in her gait -- she's bookish by temperament and worldly in the way she moves -- and poor Baankey, is a rather simple-minded ideologue when compared to her earthy, pragmatic, ironic nature.

The men are at war with themselves -- their desire to move forward is in conflict with their desire to keep clinging to the past. But Juhi Chaturvedi is no hater of men.

She loves them with all their excesses and their shortcomings, and so, when she puts unhappy, underachieving men up on the screen, you don't wish you didn't have to see them: Which is what you end up wishing, at, let's say, a, Lipstick under My Burkha.

You don't recoil when you watch Baankey taking his frustration out on a wall, or when Mirza swears at his chappals.

You don't recoil, because Sircar and Chaturvedi get you caught up in this sparring, slugging way of life without offering you the comfort of 'ethical prescriptions'.

The characters are often drenched in chiaroscuro, and this visual style, where light, even with its limited resources, seems to be plotting against darkness, ties in with the larger spirit of the film.

Much like Mirza's willful wife, Begum, who is retreating to innocence, most structures are losing their sheen, so as to reveal something less beautiful, but more basic -- bricks are appearing from behind peeled paint, and the earth itself dug down to its bowels.

None of these illustrative details are, however, used morally; this is a funny movie, and the comedy is in the realism, which often feels just tossed off.

I remember laughing loudly at a passing shot which showed the enquiry counter at a bus depot being presided over by a lady balancing a Ghoonghat on her head.

It's a sharp imagery, but lasts for not more than two seconds. Sircar and Chaturvedi have advanced beyond their advertising years; they're now all for capturing life's rhythms, on the wing.

The greatest artists are those who can move swiftly through a dense world, and in the works of such artists, paradoxes aren't unloaded upon us.

In this movie, too, satirical quips bubble forth, but smoothly. Mirza's mute caretaker as the sole witness to most acts of corruption and debauchery is a running gag with satirical undercurrents, but its power derives from the fact that it's never held up for symbolism.

There's a constant feeling that the people in Gulabo Sitabo, despite their best efforts, are being altered, by their surroundings and by the roles they've chosen to play.

The constipated bureaucracy gives Vijay Raaz's Gyaanesh Shukla his stiffness and his studied uprightness.

This archaeological officer is also an old-fashioned prude, and when he chickens out with a girl who offers herself readily, it's oddly touching.

Ayushmann Khurrana's Baankey Rastogi, a man who wants to break loose but can't, is always clothed in shirts that are two sizes too small for him.

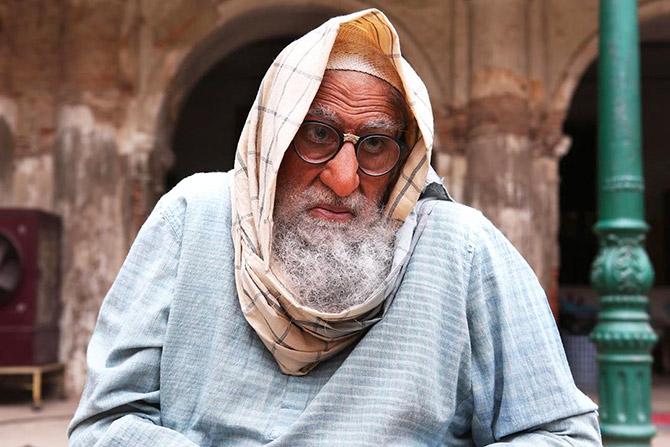

And then there's Mirza Nawab who yearns so badly to inherit a dying mansion that, his vulture-face has started to present proof of his character and, his body has become a testament to how the walls are crumbling.

This is not just Amitabh Bachchan's finest performance in the last 30 years; it's also a performance that puts the Bachchan hysteria to shame.

The angry young man is, here, a grumbling old fool, and the template-to-chronicler journey feels like an evolutionary leap.

For this role, he has quite literally made the journey, from Mumbai, the city responsible for the Bachchan template, to the state of his birth, where, one assumes, he must have spent hours as a child, studying and swallowing human frailties.

Playing Mirza as a cantankerous type would've been easy, and it would've been a source of great fun too.

But Bachchan, together with Chaturvedi, has interpreted Mirza as someone who is slipping without his being aware of it -- and this is what gives the character its tragic underpinnings.

We can perceive that Mirza's fights with his tenants aren't just driven by greed; they're also the old man's nourishment. And it's when, toward the end, he's left without an enemy, that he truly becomes a doddering fellow.

Someone who specialised in giving blood to our fantasies has transformed into an innkeeper of our most private thoughts -- and, for a loyal audience, there's a certain shock that comes with this realisation.

A legendary actor like Chaplin, in the latter part of his career, had tried to play against his star persona, and ended up becoming arch, self-serious, and uninvolving.

Amitabh Bachchan -- though he has been at it for some time now -- has, in this picture, achieved the perfect synthesis: he has found the Epic inside the Ordinary.

Mirza is not a man who can be called upon to dispense justice, but a man who stands outside his wife's room waiting for her to kick the bucket.

And yet, he's individualistic, his peevish acts coalesce lightly, and his past comes to us bit by bit: He gets formed in our head, partly by our memories of the star we could never touch, and partly by the stench of those old men and women we've intimately known.

Mirza's Begum (played by Farrukh Jaffer) is also a product of many-hued remembrances -- she's drawn from life, and from the movies.

There were times when I thought she's what Chunibala (the old lady from Pather Panchali) would've aged into, had her delusions been justly rewarded.

This is a Begum who's blacking out, and that's always a great reason for speaking the unvarnished, painful truth.

Farrukh Jaffer lines up for the camera like a memorable photo album, in that she's not merely a supplier of nostalgia, but someone who's beautiful in her toughness.

And it's the 'tough approach' that Gulabo Sitabo, for some reason, gives up in the last hour or so -- when it seems to be working for the softness that's come over people's thinking of late.

I wasn't surprised that a Twitter Champion, who specialises in broadcasting socially conscious messages in 140 characters or less, thought that the movie gathers steam only in its final moments.

This gentleman needs to be educated on the fact that an ambitious, dense work of art will always have something to say -- it's just that what it wants to say cannot often be put into a one-line conclusion.

And the last 45 minutes of Gulabo Sitabo (though it never gets so bad, as to be preachy) feels like it was assembled for the purpose of drawing up a whole bunch of banal one-line conclusions: About the self-serving nature of bureaucracies, and the condition of our have-nots (slow music, please!); about how "if we cannot settle our differences ourselves, expect the government to cash in," and "for all your smarts, remember, the ways of the world are a lot more cunning."

There's a stance taken against materialism that's too easy.

It's when the film tries to interpret its chaotic world that its humor and its generosity get defused.

A friend, I suppose, was right in his assertion that "the picture just bloody stops growing after a while!"

At this point, it feels like Juhi Chaturvedi is speaking for her characters. The script fixes its vibrant personages inside definite moral patterns and they lose their personality.

The closing moments of Gulabo Sitabo, I thought, had very few ironies that could commensurate with the density of the opening passages.

A flourish that had me smiling happened in a scene where Begum's will is read out, and you realise that she has done a Shakespeare.

Anne, Shakespeare's wife, had got the 'second best bed' and Mirza, here, gets his 'favourite chair'.

The scene of Mirza walking away with the chair is just one instance of 'quiet poetry' in a film whose charms can be best felt when its characters are arguing among themselves, or when someone's trying to beat someone else slyly, with a quick turn of phrase.

A man is taunted with, "Bahut dino baad tapkey?" and he finds the time to say, "Haan, pakey toh tapak gaye," before hurrying to the door (I wouldn't dare to translate this exchange, especially after seeing how the subtitles had made a hash of it).

In another scene, Srishti Shrivastava's Guddu and Vijay Raaz's Gyaanesh enter into a deadlock over his placement, in a sentence, of the word Agar (If).

It isn't one of Juhi Chaturvedi's trivial virtues that she's fascinated by, the lack of civility in our discourses and, our noisiness which is an inextricable part of our culture.

In her past works -- most importantly, Vicky Donor, Piku, October -- you could sense that she was trying to dramatize this aspect of the Indian reality, by formulating relationships and environments where people could be at one another's throats, where they could be openly hysterical, where someone could be losing it and still make for an interesting sight.

Here, she has moved away from dramatisation, and developed this tussling into a theme in itself.

The wonderful thing about the people in this movie is that they aren't problem solvers, and Chaturvedi is working at her full capacity when she isn't setting up their conflicts for denouements, when she isn't attaching false importance to their collisions.

Bickering is one of the major ways that Juhi Chaturvedi's characters connect with one another, and us -- in Gulabo Sitabo, it's the only way.

Feature Production: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025