'The directors of these movies to me are less like artists and more like red-pen remarkists, whose idea of a script is basically checking off the broadest of issues in the broadest possible ways: Sexism, Check. Misogyny, Check. Loving yourself, Check,' says Sreehari Nair.

At the movies -- more importantly, at the best movies -- it's often those 'small truths' that ring the loudest. It's a very small truth that Ram Gopal Varma was pursuing when he set the scene for Bhiku Mhatre's murder in Satya, in those narrow lanes leading up to Bhau's house.

Mhatre, who is shown to commit gruesome acts of violence in the most cheerfully vicious manner, unloads himself off a red Maruti van and is sent into fool's fit at children bursting crackers outside Bhau's house. 'Isko alag rakh re,' he almost pleads.

The scene then shifts to a 30-second uncut shot as Manoj Bajpai's Mhatre proceeds to make small talk with people, drink from their glasses and generally kid with those who stand there with all serious intent.

About what happens next and Bhau's treachery, we know. But all that would not have had the impact if the killing of Mhatre didn't really snorkel off, from his glee outside Bhau's residence. It wasn't the glee of a king with conquest ribbons on his robes, but that of a general who had guided the king to success; someone who will happily stay in the background, and eventually as the story goes -- fade away completely.

That entire set of sequences was such a piece of cinema virtuoso that it seemed to propel -- at least in my head -- Hindi movies ahead by 20 years, straight up.

Back in 1975, when Amitabh Bachchan had drawled out -- with the slightest of slur and spit still in his mouth -- 'Main aaj bhi pheke hue paise nahi uthatha', and left it at just that, it had given birth to a new brand of heroism: The heroism of self-worship.

With Bhiku Mhatre's glee climaxing in his ultimate downfall, that particular brand was shattered completely and replaced by a noble fool's version of heroism.

In the spirit of its times and the world of Satya, kings didn't matter anymore; it was the noble fools who indeed reigned. A small but truth of immense beauty -- evoked masterfully by Varma, working at the top of his game.

So what exactly are these 'small truths' that we are supposed to discover at the movies? Indescribable as they are, I can definitely pick them out, when I see them evoked on screen.

For instance, we saw these truths expressed in something as seemingly innocuous as the Decors and Interiors of Dil Chahta Hai. When we state that Dil Chahta Hai ushered in a whole new spirit into Hindi movies, we also in some way imply how different even the Wall Paints in that movie looked.

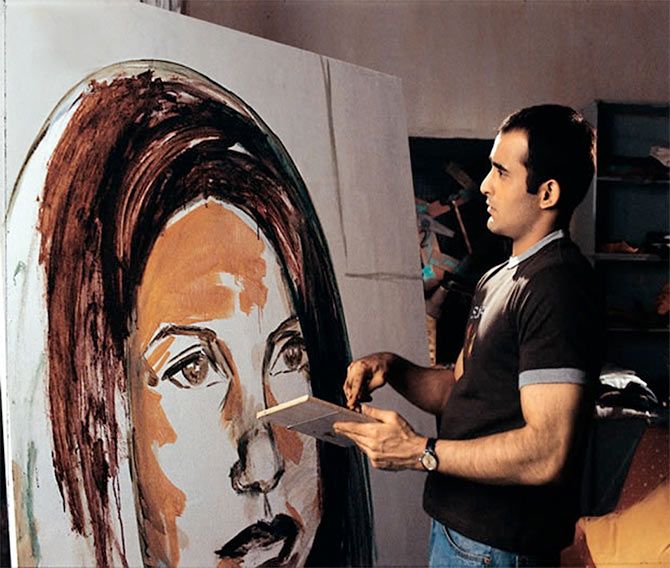

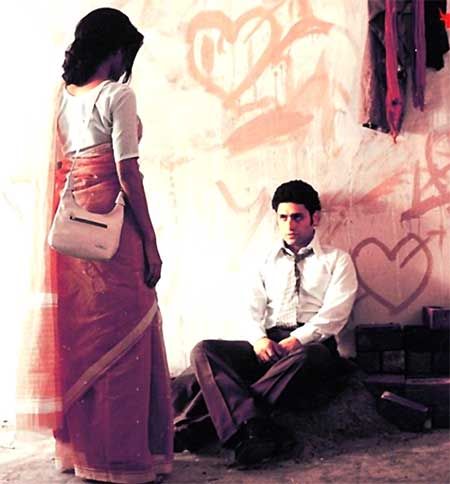

These small truths also found their way into the idealism of the characters in Hazaaron Khwaishen Aisi; characters whose endless search for that 'real connection' and failure to do so only strengthened their resolve to go further.

Hazaaron Khwaishen Aisi was perhaps the Hindi movie that to me felt closest to a Jean Renoir movie, and yet the journalistic feverishness was very much its own.

If I may digress into marketing mould for a bit: Small truths. Big Impact.

One thing, however, about these 'small truths': They can never be discovered in movies that go all blow-torch-out at making grand statements; statements about living up life, respecting women and walking the thin line between ambition and recklessness; in short, movies that invoke the spirit evident in the most generic of Facebook posts.

Dil Dhadakne Do is probably the best example of a movie that has plot-points powder-puffed with issues that Facebook deems as 'pressing'.

Pretty much my least favourite movie of 2015, this Zoya Akhtar film wasn't just an absolute pounder but also completely mean-spirited towards its actors. Special mention must be made here of Rahul Bose who probably plays the most embarrassing character of his career: A schmuck and a boob rolled into one. In the middle of a song, you see him walking down the stairs 'fake-whistling' and you feel like booing, right there.

A misconception at every possible level, there was not an ounce of nuance in the movie, not a single line that rung true and not a single performance that could salvage the proceedings.

While I had pretty much similar feelings about her first two films, in Dil Dhadakne Do everything is so orchestrated, it mimics the exact kind of virtuosity that distinguishes someone who 'likes' Facebook Posts that deride patriarchy, endorse the theory of 'following your heart' or embalm the concept of enduring love and power of nature.

I think part of what makes the really great elements in the really great movies too powerful for words is that they suggest the artistry of a director working on the edge of his unconscious.

There are scenes in Sriram Raghavan's Badlapur or Vishal Bhardwaj's Maqbool that are full of feelings -- often feelings that are odds with each other -- but these scenes never tell you how to feel.

On the other hand, a feature of these Facebook-Posts-Masquerading-As-Movies movies is that, they seem to have pre-worked every viewer reaction and calibrated all their sequences to achieve those very reactions.

The directors of these movies to me are less like artists and more like red-pen remarkists, whose idea of a script is basically checking off the broadest of issues in the broadest possible ways: Sexism, Check. Misogyny, Check. Loving yourself, Check.

When we constantly put down movies like the ones made by someone like say a Rohit Shetty, we forget that at least, those movies are generous enough to accept that they are pandering to the audience's desire for trash.

The Red-Pen remarkists, if you notice carefully, too engage in the same kind of pandering, just that their calling-card is a faux-emotional response, rolled like an English lawn.

A major excitement of watching movies is letting free parts in yourself that you didn't know existed; when something affects you, but you don't know what and how.

The excitement that these movies give, deepens the meaning of what you see on screen and you realise that at the other end is a director working purely on his instincts, and trusting his vision.

And this approach doesn't always yield good movies, mind you. But they at least give you experiences that paint you viscerally.

Ever wondered why so many young audiences love gore movies with such passion? I think it's because these movies, in their most atomic form, offer you an escape from the other kinds of movies that your schoolteachers and parents had long prescribed, as healthy for your sensibility.

What the 'Facebook Posts Films' share in terms of their consciousness are 'Advertising Films,' where a viewer is made to feel more superior and more able so that they are 'sold' on something.

What we must, however, realise is that unlike Advertising Film-Happiness, great movies offer you a more complex kind of happiness; not happiness served on a platter, but happiness buried inside mystic rituals, our prejudices, flesh, piss, sweat and blood.

© 2025

© 2025