Business reacted with caution to the reforms of 1991, and demanded protection from multinationals and imports.

Twenty-five years later, traces of that demand can still be found, reports Bhupesh Bhandari.

August 31, 1991 was a hot and humid Saturday in New Delhi. While people went about their routines, businessmen started to queue up at 7 Race Course Road, the residence of Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao, in the morning.

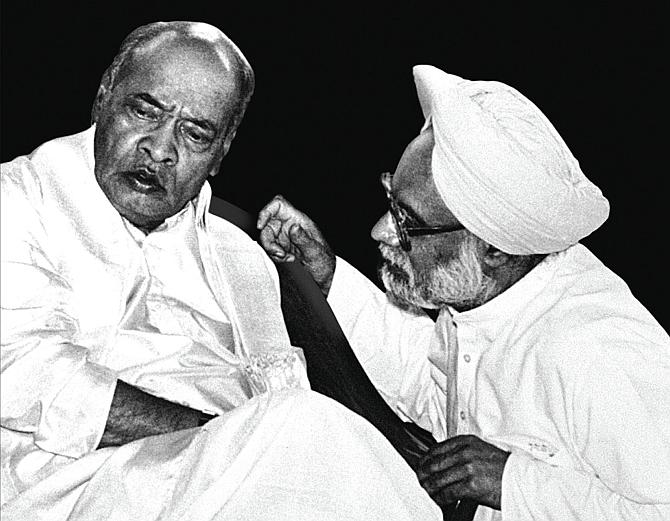

This was Rao's first interaction with business after he had taken charge on June 21. He had inherited an economy that was a shambles: Foreign exchange reserves had depleted to precarious levels, growth had plummeted and inflation was high.

Rao, along with his finance minister, Manmohan Singh, had devalued the rupee in two phases on July 1 and 3 and had, in the industrial policy of July 24, done away with industrial licensing, slashed the list of industries reserved for the public sector, allowed 51 per cent foreign investment in a whole range of sectors and relaxed the dreaded Monopolies & Restrictive Trade Practices Act.

Now was the time to take stock. The political opposition to the reform, from outside and within the Congress, had been quelled. Rao was noticeably relaxed for the meeting with the businessmen. For company, he had called Jairam Ramesh, officer on special duty in his office.

The guests were from the country's top industry associations: Rahul Bajaj and Dhruv Sawhney from CII, S K Birla from FICCI and Viren Shah from Assocham. Each association was allotted 75 minutes.

They all were jubilant over de-licensing and the relaxation in the MRTP Act, but were ambivalent about foreign investment. That they would no longer be in the driver's seat bothered them. Loss of control is always distressing.

"It put a question mark on our business model," remembers B K Modi. Till then, foreign ownership of Indian companies was capped at 40 per cent.

Modi had floated partnerships where both the foreign partner and he owned 40 per cent, while 20 per cent was held by the public. Now, from an equal partner, he was staring at the prospects of becoming a minority partner. Naturally, he was worried.

What had added to their apprehensions was the formation of the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (Rao's team was careful to use Promotion and not Processing) on August 22 and the decision to house it in the prime minister's office.

Among the first to oppose enhanced foreign ownership was auditor S Gurumurthy and the Swadeshi Jagaran Manch. Gurumurthy argued that India ought to liberalise first before it opens up to foreigners. Businessmen gravitated towards him.

"Many people from industry were in touch with me," he remembers, but refuses to name them.

Thanks to his role in exposing the Bofors payoffs, and the fact that the Manch had the RSS' support, Gurumurthy's plea wasn't entertained by the Congress government.

"I had no connection with anyone at the Centre," he admits. "Why would Manmohan Singh listen to me?"

With no sign of relief, businessmen, otherwise reluctant to criticise the government, began to openly air their grievances. Ramesh in his 2015 book, To The Brink And Back: India's 1991 Story mentions that Birla, the FICCI president, expressed his reservations about the red carpet being rolled out for foreigners.

'What I was pressing for was that foreign investment should be freed up but, following the very successful ASEAN pattern, majority should always remain in Indian hands, at least till such time that Indian industry became competitive,' Birla wrote to Ramesh on October 1, 2015 in reaction to the account in his book.

And at a FICCI seminar, Anand Mahindra argued for internal reform first and external liberalisation thereafter, which made Ramesh tell him that he sounded like a young Jawaharlal Nehru University student.

In an email, Mahindra's office says Ramesh has made, at best, a selective extraction of his comments which suited the purpose of his narrative. 'In most debates,' Mahindra would point out, 'as an academic illustration, the different models of liberalisation followed by Japan and Korea in terms of internal liberalisation preceding external liberalisation,' the email adds, 'but always took the stand that once the die was cast, it was in the interest of business to use competitive pressures to become more efficient and world class.'

Nothing worked. In his February 29, 1992 speech, while presenting the Budget for 1992-93, Singh said in plain words that he wouldn't relent. 'Concern is sometimes expressed that the policy of welcoming foreign investment will hurt Indian industry and may jeopardise our sovereignty. These fears are misplaced,' he said.

'We must not remain permanent captives of the fear of the East India Company, as if nothing has changed in the past 300 years!'

Before that, another matter had begun to give businessmen serious heartache. In his Budget speech of July 24, 1991, Singh had brought the peak rate of customs duty from 300 per cent to 150 per cent, and had indicated that more was on the way.

Then, on August 29, he appointed well-respected economist Raja Chelliah as the head of a committee to suggest tax reforms.

Businessmen now made a beeline to Chelliah and told him that if protection from imports was withdrawn abruptly, they would all sink.

"We showed to Chelliah that there was negative duty protection in many sectors," says Arun Bharatram. "Our infrastructure was backward, most industries were sent to underdeveloped areas where power plants had to be run on diesel, and the ports took one month to clear consignments."

None of that moved Singh. In his Budget for 1992-93, he cut the customs duty peak from 150 per cent to 110 per cent and said this was the 'beginning of a process in which our customs duties are gradually reduced, over a three- to four-year period, to levels comparable with those in other developing countries.'

The next year, he brought about sweeping cuts in customs duty, in line with Chelliah's recommendations, and brought down the peak rate to 85 per cent. Singh acknowledged that this would put industry under pressure but argued that with the devaluation of the rupee and reduction in customs duty on raw material, it would be able to stand its ground.

Those demanding protection were shaken. Sometime in mid-1993, top businessmen, including Bajaj, Hari Shankar Singhania, Lalit Mohan Thapar, Birla, Ashok Jain and Keshub Mahindra, met at The Belvedere Club at The Oberoi in Mumbai to take up the issue with the government. They came to be called the Bombay Club.

Their demand was a level playing field vis-a-vis multinationals.

They perhaps decided to lobby on their own because the industry associations were lukewarm to their pleas. "Our concern was not about the direction (of reform) but the speed," says Jamshyd Godrej, who was an active participant in all CII debates on policy and reform.

The Bombay Club handed over a five-page memorandum to Singh. (It demanded an equal opportunity but didn't mention 'protection' even once.)

According to Ramesh, Singh perfunctorily passed it on to Montek Singh Ahluwalia who 'filed it'. That was the end of the matter.

It was clear to the members of the Bombay Club that the government was not too happy with their initiative. As a result, the group dissipated: They never met again.

Birla, in his letter to Ramesh, insisted he was never a part of the group. 'Actually, I opposed them because they were not keen on many aspects of deregulation.'

Bajaj declined to be interviewed for this report. In October 2014, he had written in Business Standard: 'All others kept quiet after the finance ministry asked them not to go public after they made their representation -- except me.'

Did anything come out of all this? B K Modi says it did. Thus, when new sectors like telecom, banking and insurance were opened up for the private sector, foreigners were allowed only a minority stake.

Modi wanted to start a bank (he had decided to call it The Himalayan Bank) but lost out to the Hindujas who launched IndusInd Bank. But he did manage to get the licence to operate telecom services in Punjab and Karnataka, which he subsequently sold and made his riches.

The Congress-led government made other conciliatory gestures towards business. Thus, J R D Tata was in 1992 awarded the Bharat Ratna, the country's highest civilian award. Singhania, a few weeks before his death in February 2013, had told me how Rao offered to make him the Indian ambassador to the United States.

'Rao said we cannot remain enemies to the US all the time. It has to be made a friend. Diplomats will do what they can do for that. But you people can succeed better,' Singhania recollected. He had to decline the offer because his wife was unwell and he didn't wish to leave her alone.

Sometime in 1998, Honda issued an ultimatum to its partner in India, Arun Firodia: Either he should buy its 51 per cent stake in Kinetic Honda, or it will buy his 19 per cent shares.

Eventually, Firodia bought out Honda but it set the alarm bells ringing. Multinationals were now allowed to set up fully-owned Indian subsidiaries; that rendered their local joint ventures useless.

Honda had another partnership in the country: Hero Honda.

Amit Mitra, then the secretary general of FICCI and now the finance minister of West Bengal, was at the forefront to seek protection for Indian businessmen against arm-twisting by multinationals. Jairam Ramesh calls him the 'greatest champion of protectionism.'

The result was Press Note 18 of December 14, 1998. Any multinational that wanted to come on its own would have to convince the Foreign Investment Promotion Board that it wouldn't hurt its existing collaborations. The rule was in effect till 2005.

Deepak Talwar, who facilitated the entry of several multinationals, says this helped many Indian businessmen 'negotiate better exits.' Some Indians dusted out their old technical collaborations and extracted their pound of flesh.

In August 1997, ICI, the British multinational, bought a stake in Asian Paints, the all-Indian leader in the paints market. There was widespread alarm that a blue-chip homegrown company would soon be gobbled up by a multinational.

As ICI's purchase required the nod of the Foreign Investment Promotion Board, the Asian Paints promoters, Abhay Vakhil, Ashwin Choksi and Ashwin Dani, decided to challenge it.

According to Talwar, this prompted the government to put in place ground rules for cross-border takeovers, hostile or otherwise.

The Takeover Code of the Securities & Exchange Board of India made such attempts process-driven. The enactment of the Competition Act protected smaller enterprises from monopolistic abuses.

On the face of it, the demand for protection has disappeared, except when domestic industry is hurt by cheap imports, especially from China.

"The Bombay Club underestimated the resilience of Indian industry," says Suresh Krishna. Talwar says the only evidence of protection is the government's reluctance to sell the L&T and ITC shares it owns.

Still, a section of industry craves for protection, instead of achieving productivity gains, to survive. It cheers loudly every time a safeguard duty is announced.

Some believe foreigners shouldn't be given unfettered access. A C Muthiah says the Indian partners should be made to hold majority in automobile companies because multinationals came with their own component suppliers and have therefore created only a handful of Indian multinationals, "We must have some control," he says.

Bajaj, the last man standing at the Bombay Club, has little to complain: Bajaj Auto is India's most valuable two-wheeler maker. In 2010, when he was a member of the Rajya Sabha, Bajaj raised issues like 'duty-free car imports under Indo-EU FTA' and 'impact of Indo-Thai FTA.'

Old worries die hard.

T E Narasimhan and Gireesh Babu contributed to this report.

© 2025

© 2025