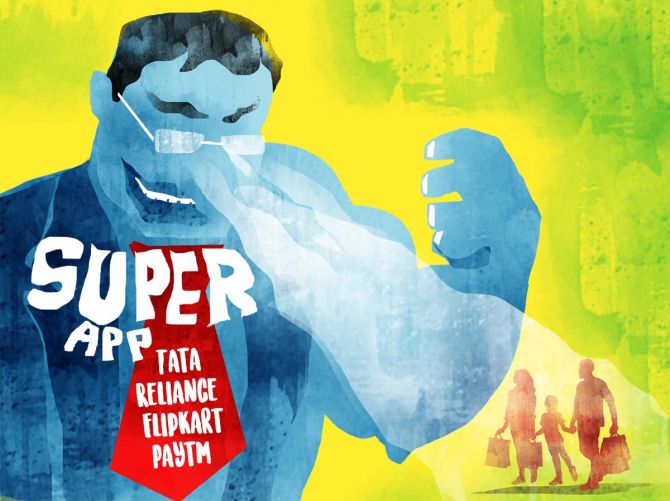

A super app is the golden key to the customer for any company selling products or services at the retail level.

Unlike the race to buy airwaves by telecom companies, airports by infrastructure companies and city gas networks by energy companies, the race to develop super apps by consumer-facing companies in India has not brushed up against any regulatory issues.

Officials at the ministry of electronics and information technology and at other regulators are happy they do not have to meddle in who among the Tata group, Reliance Industries Ltd, Flipkart or Paytm will manage to build an app that sweeps in customers.

Unlike separate apps a customer uses on her mobile to order groceries, buy food or airline tickets or just make payments, a super app can perform all these functions.

If it includes a chat box and recreation modes, the customer could become almost an appendage to the app.

The benefit for a company is awesome because it means the customer may change shopping habits through the day but remains in contact perpetually.

A physical equivalent would be a customer who never leaves a shopping mall in a 24-hour cycle, except to sleep.

The options would be vaster than a mall, though.

Holding a successful super app can also spell the difference between a successful B2C company versus one that can never foray into the space for decades.

It is, thus, the golden key to the customer for any company selling products or services at the retail level.

Just as fintech was the magic word of the second decade of this century with the global market expected to grow at a CAGR of 8.53 per cent in eight years since 2015, super apps is the buzzword for this decade, according to a Global Business Outlook report.

The word was coined less than a decade ago, though dating the origins of breakthrough concepts in the tech sector are difficult to prove with certainty.

Meanwhile, there is a massive cash burn in store for all companies planning these apps.

For instance, S&P Global Ratings has assigned a B minus rating for Singapore-based Grab Holdings.

The company, which operates in eight Southeast Asian countries, will need its “ample cash balance to support its losses and material cash burn over the next two to three years.

"(It) could achieve positive EBITDA and operating cash flows (only) from 2023”.

Grab Holdings is backed by SoftBank Vision Fund, Uber, Didi and Toyota.

Its rivals like Indonesia-based Gojek have attracted money from Tencent and Google.

The Indian companies in the race will also need the same scale of backers and the willingness to bear losses for the better part of this decade to see light.

Without this scale of cash burn and patience to last, the super apps race, like many other corporate races in India, could become messy.

Principally because there are regulatory minefields in the way.

One of those is that super apps will invade the payments space.

Both in China, where WeChat and Alipay developed as super apps, or in India for Paytm, the payments option is the holy grail.

The Indian government does not allow a corporate group the option to own banks, but what firewalls can be created if a Tata - or a RIL-owned super app offers payment services?

Already, the RIL partnership with SBI YONO has been running since 2018, and late-to-the party Tata Digital, which has just landed the responsibility to build the group’s fintech business, could be expected to announce a banking tie-up soon.

The RBI is still sitting on a working group report on whether to allow industrial groups permission to run banks, but that question could become outdated soon with super apps.

Already the RBI has relaxed rules to allow apps like Paytm to use banking channels NEFT and RTGS to settle their transactions.

The only role these apps cannot play as of now is to hold deposits, yet even here there are grey areas.

Payments banks such as Airtel and Paytm can hold deposits and both are on the way to becoming super apps.

There is more regulatory headache elsewhere.

A super app can soak in a prodigious amount of data.

Speaking about it, a CNBC report this July said this makes governments “jealous”.

India and China both do not have a data protection law and already data mountains are building up inside companies.

One of the reasons super apps or even fintech has not grown big in Europe is possibly the impact of the General Data Protection Rules.

One can expect India’s states and the central government to become involved in demands from the public to safeguard their data more effectively even as the space for super apps becomes more contested.

In this context it is not surprising that Adani Group has acquired a 10 per cent stake in government-promoted Common Service Centre SPV’s e-commerce subsidiary CSC Grameen eStore this week.

Thanks to the government policy of populating each village with a CSC centre, where people can transact myriad business from updating their kisan credit card to buying groceries, consumer durables and even automobiles, CSC Grameen has become a massive receptacle for data storage.

In a way, the company is like a data pipeline infrastructure.

The Centre holds a golden share in the holding company for CSC Grameen, with state-owned banks such as Punjab National Bank having the majority stake.

For existing players in the super app space, the competition has warmed up and so will the pressure on governments to ensure data privacy remains a priority.

And, finally, medicine.

No super app in Asia has entered the health sector in a big way.

In India, the Tata 1mg health care tie-up has broken into the space.

The company advertises it as India’s leading app-based and most trusted healthcare platform.

Expect rivals to be fine-tuning options for this space.

The Indian government has just launched the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission.

The Mission “aims to develop the backbone necessary to support the integrated digital health infrastructure of the country”.

In the post-Covid world, some of the regulatory fights over super apps among companies could well be over who gets access to this health data.

© 2025

© 2025