Nearly 490 million people of working age are outside the bounds of India's unemployment assessments.

A decrease in the unemployment rate could signal economic growth, but could just as well mean that people have given up looking for work.

A revealing excerpt from Tata Sons Chairman N Chandrasekaran and Tata Chief Economist Roopa Purushothaman's Bridgital Nation: Solving Technology's People Problem.

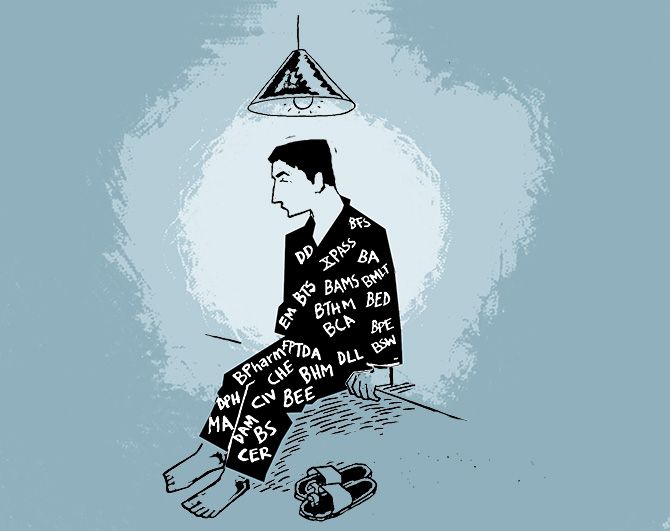

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

Bhoomi is one of 90 million who will join India's working age population between 2020 and 2030.

This will be the single largest mass of people to come of working age in any country that decade.

As it stands, the labour market they enter has three distinguishing characteristics.

First, it brims with people of working age, but who are not necessarily part of the labour force.

Second, those seeking work will find it more challenging than in previous decades.

Third, of those that find jobs, an overwhelming number will be engaged in work that is of an informal nature.

Let's look at these three essential aspects.

The first is that a large number of people who could work are not looking for work.

To gauge the labour market, people often turn to a country's unemployment rate.

They may believe the figure represents a portion of the working-age population.

That is, they may believe that India's 6% unemployment rate is for a population of 970 million.

But analysts and statisticians assess unemployment differently.

The official rate represents a portion of only those people who want to work -- those actually working, or in the process of looking for work.

It hides from view the people who aren't looking for work at all.

This wouldn't matter much in a country where almost everyone of working-age was looking to work.

In India, though, only around 450 million people had jobs and 29 million others were seeking work as of 2017.

In other words, a little less than one in two working-age people were actually working, or looking for work.

That leaves nearly 490 million people of working age outside the bounds of India's unemployment assessments.

That is why India's unemployment could be misunderstood.

A decrease in the unemployment rate could signal economic growth, but could just as well mean that people have given up looking for work.

Who are these people left so unaccounted that India doesn't know they're missing?

Who are these millions of Indians who have quit or never even joined the labour force?

We know for certain that a large number of them are women.

Only 23% of all women who can work are part of the labour force, while for men, the figure is about 75%.

Some people choose to remain in school.

For others, the jobs are too far away.

India's northern and eastern states have the highest population growth rates and large youth populations, while the jobs these restless young seek in manufacturing and services are concentrated in states in the south and the west.

There are others who have given up on looking for work.

They have tried finding jobs that match their needs and aspirations, and failed.

And the longer they spend out of work, the harder it becomes to find any job at all.

These are the discouraged workers.

The second characteristic of the labour market is a rising unemployment rate.

For the past two decades, India's unemployment rate has hovered in the 2%-3% range.

Most people looking for a job were able to land one.

However, in 2017, the unemployment rate rose to 6%.

While still not alarmingly high, it is important to look below the surface.

For some critical groups, unemployment -- the onerous search for a job -- is a matter of greater concern.

For young people between the ages of 15 and 29, the unemployment rate is nearly 18%.

When it comes to urban, tertiary educated people, the unemployment rate is 12%-15%.

For Bhoomi and her friends, the jobs landscape is a more treacherous one than they are led to believe.

They will face difficult choices on the cusp of entering the workforce.

Should they invest in higher education, only to join the ranks of the unemployed?

Or are that time and effort better spent on trying to earn what they can?

How long should they hold out on getting a job that fits their vision of the future?

Should they prioritise some, any employment over none at all?

To them, the India of the senses feels a lot closer than the India of the numbers, and families like Bhoomi's make decisions deeply aware that the stakes are high.

The third characteristic: Overwhelmingly, those who join the workforce tend to find jobs in the low-productivity informal sector.

This is not India's first rodeo when it comes to absorbing large numbers of people into the workforce.

From the turn of the century through 2011, India added 76 million workers to its workforce.

However, the majority of these jobs were informal jobs; 77% of India's employed are currently in the informal sector.

The informal sector is a world of work that exists in grey.

Everything one can say about the informal sector is an approximation.

Even definitions of the term paint a picture of imprecision.

It is unregistered, unorganised, without contracts, social security, a regular salary, or an assured volume of work.

Seen another way, if the economy were an iceberg, the informal side would be hidden beneath the water surface, encompassing a huge range of occupations.

Decades of research show that informal work is characterised by high risk, and virtually no systems of insurance, regulation or safety standards.

Most of all, it is marked by low productivity.

Many who work in the informal sector can be more accurately described as 'underemployed'.

They are less productive and lower-paid than workers in the formal sector.

In fact, they may earn as little as half of what organised, formal workers earn per day of work.

The bulk earn less than Rs 11,000 a month.

Meanwhile, because formal businesses learn and spread management procedures, protocols and best practices, they're in a better position to realise the benefits of investing in technology and assets to upgrade their production processes.

This can spark a virtuous cycle of productivity and growth for a business.

In turn, they are incentivised to invest in their employees, who form the other crucial part of the productivity equation.

Workers in a labour market with more formal opportunities see greater job stability as well as expanded future job prospects; a legal and regulatory framework; sanctity of contracts; workplace standards and streamlined access to credit.

India's great search for work is really about a pursuit of stable work in the formal sector.

It is a goal for which India's young go to extremes.

For two hours every morning and evening, over a thousand students assemble on the Sasaram train station platform in Bihar to prepare for their competitive examinations.

The station-waale ladke (station boys), as they're known, travel from distant areas to study under the station's lamp posts -- the station being the one public space with uninterrupted electricity.

All of them hope to find government jobs -- prized for the security they provide -- after passing their exams.

There is no dearth of lamp-post students in India, and competition for each job is intense.

For the contenders who miss out, a life in the informal sector awaits.

In comparison to these students, Bhoomi is one of the few facing the jobs landscape with decent preparation, but the odds are still stacked against her.

Excerpted from Bridgital Nation: Solving Technology's People Problem by N Chandrasekaran and Roopa Purushothaman, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

© 2025

© 2025