| « Back to article | Print this article |

What are the skills that managers need to succeed in today's volatile global business scenario? What should B-schools do to deliver more value to their customers?

A survey conducted by the London Business School reveals some home truths. . .

What makes a manager world class, what training is needed to stay up-to-date and up-to-speed? What do CEOs look for when recruiting future global leaders for their organisations?

These are topics of repeated analysis and continuing debate. Hence over the last year, as part of an exercise to determine London Business School's role in the education and training of the next generation of business leaders, we conducted more than 100 face-to-face interviews with managers from global companies across a variety of industries and geographies.

Back to reality

The starting point in any analysis must be the reality of business as it is practiced. The most glaring business reality of today is the global scope of business and of managerial work. Over the last two decades this has been transformed.

For example, GE wasn't a global company in the 1980s; it was barely international. First under Jack Welch, and now under Jeffrey Immelt, it is becoming genuinely and persuasively global.

Globalisation is not a neat euphemism for American economic imperialism. The reality is that globalisation is omnipresent and multicultural.

Take telecommunications where the leading companies include Nokia from Finland, Siemens from Germany, Korea's Samsung, the Japanese-Swedish Sony Ericsson and America's Motorola. Alternatively think of the automotive giants: Toyota, Honda, Daimler, BMW, GM and Ford. Building such multicultural companies is a relatively new phenomenon.

The dynamics shaping global business are equally multi-faceted. Customer needs are changing at an ever-faster pace. Accelerating technology innovation is allowing shorter product development cycles. High-tech supply chains mean we can now source products from the lowest cost locations wherever they are in the world. Low cost communications technology allows the outsourcing and off shoring of sophisticated services from countries with low labor costs.

Entrepreneurs in those countries are rapidly building multi-lingual and multicultural businesses to serve those needs. Huge new segments of consumer demand are rapidly growing in India and China (the world's biggest mobile phone markets and second largest in PCs). Global brands are racing to offer products and services tailored to local market tastes.

Put these dynamics together and it becomes clear why speed, agility, and adaptability are critical. Organisations are changing to meet this challenge. They are becoming less layered, more geographically dispersed and less encumbered by boundaries both internally and externally.

Decision-making and execution are cross-functional and cross multiple geographies. At the same time, many activities such as supply chain management, product development and back office processing have become purely process-oriented.

For individual managers this means that, as well as their primary role, they have to spend time working on change management, quality improvement or process redesign teams.

Most, if not all, work is now done in teams. Roles are becoming more fluid and less structurally defined. Militaristic command and control is fast disappearing.

Now back to the research. It was begun in response to a suspicion that our customers 'had issues' with our product.

Our questions to them were basic. What are the skills managers require? How might they change in the future? What must your people be able to do for your company to remain successful? And how can we help you meet these needs?

We expected their answers to be as straightforward as the questions. So we were surprised by, both, the breadth of the responses and what they revealed about the future direction of executive education. The corporate leaders we interviewed indeed produced an extensive list of qualities they desired in future recruits, but almost none involved functional or technical knowledge.

Rather, virtually all their requirements could be summed up as follows: the need for more thoughtful, more aware, more sensitive, more flexible, more adaptive managers, capable of being molded and developed into global managers.

The objective has been to identify the global business capabilities required of managers today and in the future so that London Business School can better tailor its products and services to help individuals develop those capabilities.

The basics

There are three elements to global business capabilities:

1. Knowledge: The foundation of global business capabilities is knowledge. Knowledge can be defined as understanding gained through experience or study.

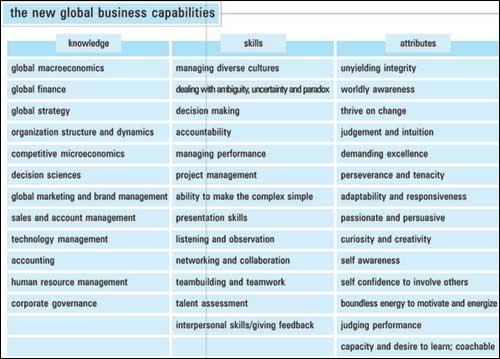

Knowledge covers subjects such as strategy, economics, decision sciences, and accounting. Knowledge is the base information required by successful managers to operate at the lowest managerial levels. Knowledge covers the basic functional areas (see table) and of course, each of these subject areas now has a global perspective.

Knowledge is manager base-camp and accumulated early on in the career of a manager. Indeed, the clear trend is toward assembling basic knowledge at an earlier age. This is most clearly manifest in the rise of undergraduate business degrees and the increasing business element in degrees as a whole.

Such knowledge is at the heart of the world's MBA programme. It can be taught by a professor on a podium in a lecture hall, but such knowledge is only part of what recruiters now look for. Knowledge alone is insufficient and increasingly short-lived.

2. Skills: The second element to global capabilities is the acquisition of skills. Skills are practiced ability, the learning acquired through the repeated application of knowledge (see table) and tend to be acquired during the middle career period when people move into general management roles.

Business is action-oriented, and skills are fundamental to effective management. However, skills are largely peripheral elements of most MBA programmes.

Universities generally assume that the acquisition of skills is the responsibility of companies and individuals, the happy by-product of experience. This assumption no longer automatically holds.

The skills required of managers are global and complex, and require professional rather than ad hoc training. Although many skills needed by managers are often specific to particular situations, business schools can and must work with their end users to develop in their students a set of universal skills, such as teamwork skills, project management, performance management, and talent assessment.

3. Attributes: Attributes are individual qualities, characteristics, or behaviors focused on leadership (see table) and are usually acquired at a later stage in a manager's career.

The attributes required for business leadership can be developed in a business school at least to the same degree as business knowledge and skills can. The attribute cited most frequently by our interviewees was integrity, the ability to remain consistently true to clearly expressed values.

In some circles, integrity is thought to be culture-specific and, as a result, beyond the mandate of a global educator.

Our research suggests otherwise. "Unyielding integrity is key in the developing world; a large portion of integrity can be globally defined," said Peter Wong, Director, Standard Chartered Bank in Hong Kong.

If integrity is a universal attribute and one regarded as critical to business success, schools must pay serious attention to its development.

Global companies are already applying our three metacapabilities, at least implicitly, in the way they identify, develop, and assign managers to tasks and roles.

Our interviews confirmed that knowledge has become a basic entry requisite for the budding global manager -- a commodity that companies both assume and overlook their recruits' skills and attributes clearly are of more import to them.

Jeffrey Immelt, Chairman & CEO, GE, for example, talks of using the company's celebrated Crotonville executive development facility to give managers "an external perspective, global and technical savvy."

Lehman Brothers, for example, has adjusted the emphasis of the core competencies it requires from employees. Previously, it emphasised analytical skills and prior experience. Today, the investment banking company focuses on leadership potential and initiative, as well as problem solving and technical skills -- a shift from knowledge to skills and attributes.

Many other major corporations, including HSBC, Unilever, and MasterCard, have made substantial investments in identifying the values and behaviors necessary to succeed. Having done so, they can screen applicants against these values and behaviors and focus their development efforts upon those they hire. issues raised

Our research suggests that managers require, and will require in the future, a daunting array of capabilities. The broad ranging nature of these is reflected in the work of business thinkers.

As Warren Bennis observes in his book, On Becoming A Leader, the next generation of business leaders will be more broadly educated than their predecessors. They will have to possess boundless curiosity, limitless enthusiasm, have faith in people and in teamwork, have a willingness to take risks, remain devoted to long-term growth rather than short-term profit, be committed to excellence; and display readiness, virtue and vision.

Many of Bennis' themes are echoed in the global business capabilities we identified. An interesting element to this in our interviews was that the senior managers we talked to weren't daunted by the list.

They were comfortable with the complexity they had to contend with. Few suggested a shorter list or that two or three elements were the distilled essence of executive capabilities. Complexity is a fact of global business life and accepted as such.

Customer driven education

The shift in companies' recruiting and development emphasis from knowledge to skills and attributes means that each business school must pick the place it intends to compete, creating a differentiated mix of teaching and training opportunities drawn from the three meta attributes companies require of their recruits.

Given the employers' shift in focus, business schools must change on three fronts:

These three adjustments do not mesh easily with the traditional model of business education, which has emphasised knowledge first, skills (primarily analytical skills) second, and attributes a distant third.

It is only in recent years, for example, that teamwork, leadership and communication skills have begun to be taken seriously on MBA curricula. While corporations both large and small have globalized, have business schools globalised their methods, content, personnel, scope, and ambitions to the same extent?

Mostly not. Global experience must play a much more significant role in business school education. "MBA students should spend time overseas to broaden their knowledge and understanding of different cultures and markets,' said Eastman Kodak Company Director Rick Braddock.

Business schools must draw in faculty and students from around the world; their global mix and awareness must match that of the business world.

In particular, increasing use should be made of exchange programs, summer internships, in-company projects, and shadowing of global managers at work in the real world.

Action orientation

For business schools, providing more action oriented programs is the biggest challenge. Good and timely decisions are crucial to business success. Good decisions depend on an ability to integrate a complex blend of fact-based analysis, judgment, and intuition.

Little else deserves as much attention in business education, but the schools are ill equipped to provide real training in decision making.

"Companies still complain that managers roughly know what they need to do, but most don't do it," said the late Professor Ghoshal.

"So the ability to take action is another skill that is coming to the fore. Managers need the capacity to take action; the capacity to build personal energy for taking action; the capacity to develop and maintain focus in the midst of distracting events. They require action-taking ability -- call it emotional capital if you wish."

Judgment and intuition are developed through repeated experience. The challenge for business schools, therefore, is to build a rapid-fire set of decision-making experiences. So it may be time for schools to rethink one of their sacrosanct components: the case.

Harvard Business School MBA students study and prepare more than 500 cases during their time at the school. The trouble is that the classic business school case, as normally construed, is time consuming, individually oriented, and too specific to be generally applicable. In addition, the process of preparing a case is largely intellectual.

Moreover, the cases now produced tend not to be sufficiently global in content or perspective. Although Harvard produces about 750 new business cases and other teaching materials each year, there is a shortage, for example, of cases written specifically on Asian companies.

Those produced tend to focus on the challenges faced by Western companies in doing business in Asia, or are geared toward educating Western students in the Asian business culture.

Business schools must, therefore, develop a set of virtual decision making experiences that emulate the real world of business. These minicases -- akin to flight simulators for pilots in training -- will be shallower, but more generally applicable, than traditional cases.

They might involve teams, with students playing roles that mimic those taken by real managers, in real teams, in real life. Business practitioners could take part.

Why, after all, should post-graduate executive education students and full time MBAs remain divorced from one another? The key is to create repeated and different experiences with examination of the implications and learnings from the decisions.

Aspiring athletes learn the theory of the game, but their coaches emphasise practice to acquire the complete range of knowledge, skills and attributes required to succeed. Having honed their physical capabilities and refined their technique, elite athletes work on mental attitude, completing their own triad of metacapabilities.

Managers should go through similar attaining throughout their careers - building and then refreshing their capabilities -- with business schools reincarnated as providers of fertile global practice grounds rather than simply purveyors of one dimensional knowledge.

These challenges -- to be global, to rethink the learning process, and to become more action oriented -- are substantial ones. The hard commercial reality is that business schools simply have to change. Luckily, business schools have an impressive capacity for self-renewal.

Laura D'Andrea Tyson is the Dean of London Business School. Nigel Andrews is Partner, Internet Capital Group and also the Governor of London Business School.

Published with the kind permission of The Smart Manager, India's first world class management magazine, available bi-monthly.