| « Back to article | Print this article |

Education budgets of world's top economies

In 1919, three decades before Independence, Rabindranath Tagore declared, "All over India, there is a vague feeling of discontent in the air about our prevalent system of education. Signs have been numerous of a desire for a change."

And yet 90 years later, as India emerges as an international economic powerhouse, its education expenditure is still less than 4 per cent of its GDP, where it has hovered for the past decade, somewhere between 3.0 per cent and 3.7 per cent.

In the Union Budget 2009-10, Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee pledged to improve funding for higher education. But conspicuously absent, critics say, was a clear commitment to improve Indian education as a whole.

Figures from the CIA World Factbook show that, of the world's twenty largest economies, only Japan, Russia, China and India are below this 4 per cent line. And Japan and Russia -- comparatively wealthy countries with smaller populations and already-established education infrastructure -- find themselves in situations very different from that of India and China.

Compare this with Sweden, which spends a robust 7.1% of its GDP on education, and it's clear that the Indian government may be doing its young citizens a disservice.

Here, a look at the world's twelve largest economies, and how much each spends on education as a percentage of its GDP.

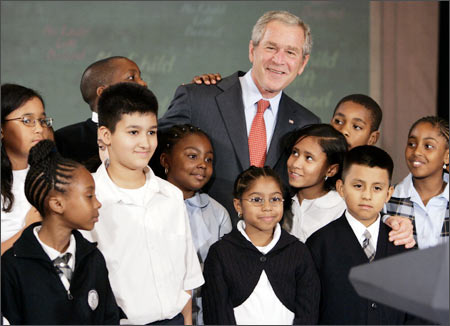

Uncle Sam foots the bill

United States -- 5.30 per cent in 2005

Probably because it's the world's largest economy, by a wide margin, the United States is the world's largest spender on education.

But, judging by its healthy 5.30 per cent of GDP education expenditure, America considers education to be a serious priority.

To give an idea of just how much the US spends on education, consider this: The state of New York spends nearly $15,000 per pupil per year (about Rs 7.5 lakh).

In addition to its heavy spending in primary and middle school education, America also boasts the world's most extensive higher education system ecosystem, including public universities like University of California - Berkeley, University of North Carolina and University of Virginia.

Japan gets more from less

Japan -- 3.5 per cent in 2005

Of all the world's truly wealthy nations, none spends less than Japan on education.

Education expenditure as a per cent of GDP has fluctuated between 3.4 and 3.7 in recent years, but has never gone above this modest mark.

Still, Japan's students consistently perform at the very highest level when compared to their international peers.

Many theories have been propounded to explain this phenomenon, from inherent intelligence, to Japan's massive private tuitions industry (about Rs 80 billion per year), to culturally-ingrained respect for authority and hard work.

The dragon rises

People's Republic of China -- 3.3 per cent in 2007

Although China and India face many similar challenges in terms of education, it's clear that the world's most populous country is rapidly moving to expand its educational horizons.

There was a time, just a decade ago, when China's educational expenditures were barely 2 per cent of its GDP. Today, that number is quickly moving toward 4 per cent.

It's reported that, in one generation, China has rapidly increased the proportion of its college-age population in higher education, to roughly 20 per cent in 2005 from just 1.4 per cent in 1978.

China's literacy rate is now comfortably above 90 per cent, and rising.

Germany has seen recent reform

Germany -- 4.60 per cent in 2004

Germany, like Japan, for years has had a strong economy and a relatively wealthy population. Also, like Japan, the country has never spent as much on education as compared to its peers.

In fact, Germany's educational expenditure as a percentage of GDP is one of the European Union's lowest. It has, however, grown in recent years.

In the 1990s, the number hovered around 3.3 per cent. In the early part of this decade, although Germany has enjoyed a reputation as educationally strong, internationally testing conducted by the Programme for International Student Assessment showed that Germany was becoming increasingly weak in reading and math.

It ranked 21 of 43 nations tested in reading and 20 of 43 in mathematics and natural sciences.

The outrage over these results led to the reforms that have seen educational spending increase past 4 per cent.

France, one of Europe's big spenders

France -- 5.7 per cent in 2005

France is proud of its highly centralised and highly organised education system, which has a rich history at the primary, secondary and higher education levels.

As a result, the country spends a lot on their education as a percentage of GDP, more than any non-Scandinavian country in Europe.

In recent years, however, the number has begun to shrink, as economically conservative centre-right governments under first President Jacques Chirac and later President Nicolas Sarkozy have chipped away at some of France's socialist leanings.

Throughout the 1990s, the education expenditure as a percentage of GDP hovered around 7 per cent. Today, it's less than 6 per cent.

Recession threatens UK's education budget

United Kingdom -- 5.6 per cent in 2005

At 5.6 per cent, the United Kingdom's education expenditure as a percentage of its GDP is about the average in the European Union. It's also similar to countries like the United States and the Netherlands, and significantly higher than European powers like Germany and Italy.

However, the UK's economy has been badly hurt by the global recession, and it's expected that many social programmes will be slashed in the future, including education.

Russia and Italy face education budget cuts

Italy -- 4.5 per cent in 2005

Education has become a hot button social issue in Italy in recent years, as many activists claim that schools are falling apart and under funded.

When a report was released in 2008 that said up to 97 per cent of the country's relatively modest education budget was going to pay teachers and administrators, leaving only 3 per cent for operational expenses, there was an uproar in the circles of economic conservatives. They immediately called for the axing of nearly 100,000 teachers and administrators, and the closing of smaller schools.

Last October, when the country's education minister, Mariastella Gelmini, managed to push through the aforementioned cuts and reforms, which were purportedly meant to make the country's education system leaner and more nimble, it sparked off a wave of protests.

Russia -- 3.8 per cent in 2004

Russia boasts one of the world's highest literacy rates, at over 99 per cent, but spends comparatively little on education.

The effects of this paradox are borne out in recent results from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study and PISA student assessments, which showed that Russian primary school students are the most literate in the world, but that their 15-year-old Russian counterparts are significantly below average in reading comprehension and other disciplines.

To make matters worse, over the past five years, education spending as a percentage of the GDP has fallen sharply.

Former President and current Prime Minister Vladimir Putin shoulders much of the responsibility for this, as under his auspices, in one year, 2004-2005, education spending plummeted 20 per cent while law enforcement and military spending grew by the same value.

As the country simultaneously continues to remilitarise and braces for the continued effects of the global recession, social spending programmes will likely remain on the chopping block.

Best of the BRIC, Brazil aims higher

Spain -- 4.2 per cent in 2005

Spain has a rich culture of private education, from primary schools through universities, and this is reflected in the education budget. The country's education expenditures as a percentage of GDP have been slowly but surely shrinking since the 1980s. Today, Spain spends less on education than the vast majority of developed countries, and quite a few developed countries.

Brazil -- 4.3 per cent in 2006

As a percentage of its GDP, Brazil education expenditures are about 4.3 per cent, the highest of all BRIC countries. Given that 12 per cent of its population is still illiterate, the Brazilian government sees room for improvement. It has pledged to increase the rate to 7 per cent in coming years.

Canada -- 5.2 per cent in 2002

In this decade, Canadian students have consistently performed near the top of PISA examinations.

Many in the country attribute this to massive education spending in the early 1990s, when Canada's education expenditures as a percentage of its GDP approached 9 per cent.

In recent years, education spending as a percentage of the GDP has begun to shrink, however, down into the 5 per cent range. Whether Canada's future students will be negatively affected by this is as yet unkonwn.

India still far below its goal of 6%

India -- 3.20 per cent in 2005

For decades, since the 1960s in fact, various committees have advised the government to increase educational expenditures to 6 per cent of the GDP. The government has dutifully promised to do just that. Unfortunately, the reality has been quite different, and that rate has hardly ever been even half that.

Higher education is clearly the primary focus as the government has increased the plan outlay by Rs 2,000 crore (Rs 20 billion), from Rs 7,593.50 crore (Rs 75.935 billion) in the interim budget to Rs 9,596 crore (Rs 95.96 billion).

While this is aimed at increasing the gross enrollment ratio in higher education from the current rate of 12.4%, there were no special incentives for the private sector to join this effort.

The CIA World Factbook recently pegged India's education spending at 3.20 per cent of its GDP, using figures from 2005.

Although critics concede that the newly announced education budget contains a number of provisions for improving the country's higher education system, India has the lowest literacy rate of all the BRIC nations, at about 66 per cent.

This chronic under funding has had a terrible effect on the nation's education system, say NGOs. Lack of payment has been surmised as the reason why as many as 25 per cent of the nation's public sector teachers were absent during a recent survey.