Photographs: Reuters Madan Sabnavis

By a continuing process of inflation, government can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. -- John Maynard Keynes

Inflation exists in all countries and while the level of tolerance is different depending on the overall circumstances, a pertinent question raised is why the central bank cannot target a zero inflation rate.

After all, if we do not want prices to rise by x% and let us assume for the purpose of argument that it is possible to steer this rate to the desired level based on policy measures, why can't it be 0%, even though it may never happen.

The first reason is that prices are bound to rise because there will always be several demand-supply mismatches in the economy. There can never be a simultaneous equilibrium in all markets considering that information symmetry is impossible.

Secondly, a bit of inflation is a must to spur economic activity. If prices were theoretically supposed to remain unchanged then there would be little incentive for production to become more efficient.

For example, if the price of an automobile is Rs 400,000 and that remains for all the inputs too, then the company can never increase its rate of profit growth. Workers will receive the same wage and will have a problem facing rising prices in other areas.

Investment would stop and growth will be affected. Therefore, the necessary condition for investment to take place is that prices should keep increasing. Also it has been observed in India that phases of high industrial growth have normally been associated with rising prices.

Therefore, inflation is a must for economic activity to take place.

. . .

Excerpted from: Macroeconomics Demystified, by Madan Sabnavis. Reproduced with permission from Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited. Price: Rs 295. Copyright 2008.

Why central banks target x% inflation and not 0%

Image: The Reserve Bank of India.Photographs: Reuters

Lastly, at the practical level the central bank knows very well that prices are affected not just by domestic conditions but also by global factors.

Also, as inflation is both demand and supply determined it has powers over only the growth of the demand side factors. This being the case there is a need to define a range of inflation, which is tolerable for the economy beyond which the authority would intervene and repress the market.

It indicates that beyond a point the central bank may be willing to sacrifice growth over inflation and would increase interest rates or make the reserve requirements more stringent.

Control of inflation

The measures used to control inflation depend essentially on the posture taken on theory. The Keynesian model does not consider it to be very important as long as full employment is not attained.

If full employment is attained then the solution is to simply increase tax rates to cut down on spending. In real life such a measure may not be feasible especially if it is targeted at cutting down spending. More likely people may cut down on savings when tax rates rise as households fix consumption levels.

The monetarist view would be to lower the ability to spend through borrowing. Therefore, money supply is targeted with the focus being on bank credit to e commercial sector.

. . .

Why central banks target x% inflation and not 0%

Image: Aircraft fly past the Indian flag.Photographs: Reuters

Monetarism prefers this route to check inflation and all central bank governors talk incessantly of curbing growth in money supply to check inflation. But, this works only when there is so called demand-pull inflation. It will not work when there is cost-push inflation.

In fact, if there is cost-push inflation and the central bank decides to invoke stringent monetary policy measures, there could be some significant negative effects. Lower credit to the commercial sector will hold back investment plans. This will mean cutting back on growth in general which will simultaneously also mean large-scale layoffs.

This leads to the most cumbersome phenomenon of stagflation when all theories fail to provide a viable solution.

Stagflation actually queries the tenets of both Keynesian and Monetarist economics as having simultaneously high inflation and unemployment defies their basic pillars.

Cost-push inflation can be controlled either by increasing supplies or direct price intervention. Normally, removing restrictions on imports so that there is a free flow of goods and services across borders eases shortages.

The government can also come in and import products especially foodstuffs when there are acute shortages, which happens in India especially when food items are involved. This is pragmatic considering that very often it may not be possible to increase production immediately in the short run especially for agricultural products.

. . .

Why central banks target x% inflation and not 0%

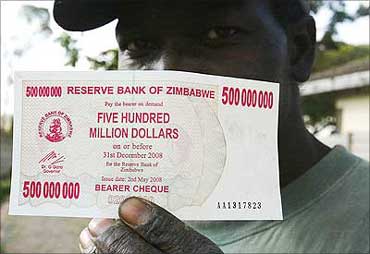

Image: Inflation in Zimbabwe touched record heights.Photographs: Reuters

If all else fails or when the cause of inflation is a global factor, then the government can intervene directly through price controls.

In India, this is seen through administered prices of petroleum products. The government often holds back passing on the full impact of an increase of the landed cost of crude oil by subsidizing the consumer when withholding the prices of petroleum products.

As mentioned earlier, the government protects the oil companies through the issue of oil bonds on which interest is paid and the latter enters the subsidy bill of the government which eventually show in the fiscal deficit.

Ultimately, what must one do?

As observed across the world there is nothing sacrosanct about these targets and there can be no benchmarks as such. Countries with hyperinflation, as was the case in Latin America in the 1980s, would actually not mind having an inflation rate of 10-20%, while there has been the case of Zimbabwe in 2007 running an inflation rate of over 7500%.

Normally, these targets are fixed based on past history as well as the overall growth scenario.

. . .

Why central banks target x% inflation and not 0%

Photographs: Reuters

Inflation is hence a very important indicator for everyone around. For politicians it can mean losing or winning an election. It happened in India in 1980s, when the government lost the elections on account of high onion prices. The opposition can use this to blame the government for poor governance.

For policy makers it is critical because they need to know how this inflation has been caused so that they can accordingly work on it to bring it down.

Higher prices due to supply pressures would probably mean increasing imports, which is within the realm of export-import or trade policy. Suitable facilitation may be needed from that quarter.

While the common man may not be interested in understanding Keynes and Friedman, he surely understands inflation as it hits him hard. Also a lot of numbers that are used as evidence of achievement such as income, profits, trade and wages, are scaled down when expressed in real terms or rather adjusted for inflation. Therefore, the number as such is important.

But one needs to be cautious about which inflation rate is used and the exact concept chosen as the difference can be significant leading to varying conclusions.

Excerpted from: Macroeconomics Demystified, by Madan Sabnavis. Reproduced with permission from Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited. Price: Rs 295. Copyright 2008.

article