Photographs: Reuters Akshat Kaushal and T E Narasimhan in Tiruppur

Dressed in a loincloth, a frail-looking 84-year-old A P Kandaswamy, who is a farmer and also the president of the Noyyal River Ayacutdars Protection Association, greets us with a glass of water from his well.

"Don't drink it. Just taste it," he warns. "Drinking can be harmful for your health." Kandaswamy takes us to his farm and shows us what remains of it.

"I had 1,400 coconut trees, now none remain," he says. "There are some with fruits, but we don't sell them, as they can be harmful for anyone who consumes them," he adds.

This summarises the state of affairs in Tiruppur -- a town near Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu that accounts for almost 80 per cent of all the cotton knitwear exports from India.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Photographs: Reuters

Once a bustling place with great ambitions, Tiruppur is facing a devastating reversal of fortunes because of the deadly industrial effluent that its industries have emptied into the ground and rivers nearby and the resulting contempt order that Kandaswamy filed in the Chennai high court some time ago.

This order has recently forced the industry to shut down.

Dyeing in Tiruppur has been the lifeblood of much of the community since the 1970s. It has also spelt death.

"Only I live here. My children have all moved to Erode -- because of the water, they had pregnancy related complications. Even the cattle are unable to reproduce," says Poontai.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Here, the river Noyyal, which emerges from the Vellingiri hills in the Western Ghat and has a basin of 180 kms, can easily be mistaken for a drain.

"The colour of the river is green. If the water was clean it would have been red," say farmers.

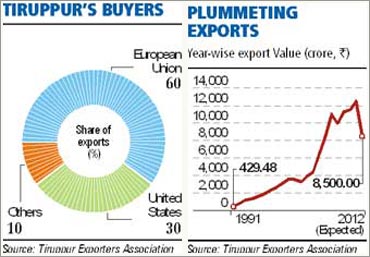

The Chennai court order has meant the demise of a once-booming business in knitwear. As an impact of the closure, the first-quarter knitwear exports have declined by Rs 1,200 crore (Rs 12 billion) this year alone and exporters expect a loss of Rs 4,000 crore (Rs 40 billion) for the year.

According to some estimates, the industry is bleeding Rs 10 crore (Rs 100 million) every day. "At least 45,000 workers, who were working in these industries, have been left with no work and have returned to their villages," says S Nagaraj, president of the Tiruppur Dyeing Association.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

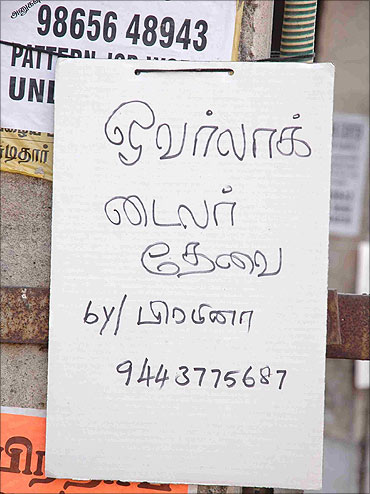

Image: A 'wanted' sign asking people to join garment units in Tiruppur in better times.Photographs: Rediff Archive

Ghost town

The impact is more than visible on the streets of Tiruppur. In December last year, traffic was reduced to a crawl on its narrow roads. Now, however, they have a deserted look about them.

"I can zip through the town now," says Hariharan, who operates a taxi service. "After January, there has been no traffic on the streets," he adds.

Naturally, anyone who has benefited from Tiruppur's past boom has been hit badly, especially the likes of hotel owners and mobile-phone sellers. According to Ashok Kumar, district head, Tiruppur Mobile Phone Services Association, in the last four months alone around 30,000 connections have been disconnected.

"Till January, there were about 2,500 shops here involved in recharge, with an average collection of Rs 2.5-3 lakh (Rs 250,000-300,000) a day. This has now come down to Rs 1-1.5 lakh (Rs 100,000-150,000)," says Kumar.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Image: Dyeing hub faces reversal of fortunes, pollutes area, kills itself.Photographs: Reuters

The rise of a boom town

Two decades ago, Tiruppur was relatively unknown. Veterans here say the shift towards it began after numerous strikes in Kolkata during the 70s -- then, the dyeing-hub of India -- forced industry to look for an alternative place.

Since Tiruppur was already involved in bleaching, and it was close to Coimbatore, dyeing units began to emerge. However, a real change in the town's fortunes occurred after liberalisation in the 1990s.

Then, total exports from the town were Rs 289.85 crore (Rs billion), rising to Rs 12,500 crore (Rs billion) last year.

In 1996, however, seeds of the long fight between the industry and the area's farmers were sown when the Taluk Noyyal Canal agriculturists filed a petition in the Madras High Court to put a stop to dyeing companies releasing effluents into the river.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Image: Inside a garments export factory in Tiruppur.Photographs: Rediff Archive

The matter came to an end after the dyeing companies agreed to take steps to reduce the release of effluents.

However, the steps taken by the units failed to impress the agriculturists and they approached the court again. This time, in 2006, the high court laid down conditions and made it mandatory for units to follow a policy of 'zero-liquid discharge'.

That didn't happen and a contempt petition was ultimately filed by the farmers. On January 28, the court ordered closure of all dyeing and bleaching units. Later, in March, the court also refused to provide further time for these units to achieve zero-liquid discharge. At that point, the die for the survival of Tiruppur had been cast.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Image: Textile workers protesting.Photographs: Reuters

Struggle to survive

For Tiruppur's garment manufacturers, the court order is the final blow in a series of recent setbacks. "We have not completely emerged from the 2007 recession and now, because of the dyeing units being forced to close, our margins have further shrunk by 10-15 per cent," says a garment manufacturer who has an annual turnover of Rs 30 crore (Rs 300 million).

The reason? "We are forced to send our garments to other places for getting them dyed," says P Nataraj, managing director of KPR Mills. "We have lost 30 per cent of our business. It is very difficult to sustain this mode of working in the long run. It is not feasible. The government and the industry have to find a permanent solution," he adds.

Solutions

One of the solutions being floated is the construction of the Marine Discharge Plant, which would transfer effluents from all the bleaching, dyeing and processing units of the state through a common pipe in the sea.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Photographs: Reuters

The Thirteenth Finance Commission had also allocated an amount of Rs 200 crore (Rs 2 billion) for this project. As of now, no work has started on this project.

On August 2, the Tamil Nadu government also gave a Rs 200-crore (Rs 2-billion) loan to the affected units on zero interest. In addition, the government would also pay a Rs 18-crore (Rs 180-million) compensation to farmers who were affected by the pollution.

Plus, a high-level committee under the textile ministry, headed by the Textile Secretary Rita Menon is also meeting on August 24 to take stock of the situation. However, in spite of the government's efforts, manufacturers are still sceptical.

"Till now the government has failed to perform its role properly," says Raja Shanmugham, managing partner at Warsaw International.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Image: Inside a textile factory in Tiruppur in good times.Photographs: Rediff Archive

If this is indeed true, then these manufacturers have only one entity they can rely on -- themselves. "There are technologies available, which can be adopted by the dyeing units in Tiruppur," says J Thulasidharan, chairman, Southern India Mills' Association (Sima).

However, manufacturers don't want to use them as they have an effect on profits.

Flight to foreign shores

Not surprisingly, other countries are taking over the shortfall created by the Tiruppur impasse. "Tiruppur's loss is India's loss," says A Sakthivel, president of the Tiruppur Exporters Association.

"The confidence of our buyers is falling as we are unable to complete the orders on time. Most of the international buyers are moving towards China and Bangladesh," he adds.

. . .

Why India's largest textile exports hub is dying

Image: Jobs had come back to Tiruppur after the recession receded, but pollution is killing the town.Photographs: Rediff Archive

Meanwhile, as a temporary solution, manufacturers are sending their garments to places such as Ludhiana, Kolkata, Surat and Mysore for dyeing. However, they say that this has led to a 15-20 per cent increase in the cost of manufacturing, and a sharp drop in demand.

A more permanent shift to alternative places has also already begun. "Sima has set up a company called Sima Textile Processing Park, which has set-up an industrial park in Cuddalore," says J Thulasidharan, chairman, Sima. "So far, ten units form Tiruppur have come up there," he adds.

Farmers allege that the manufacturers of death haven't yet completely stopped operations. "In spite of the Court order, there are still some units that continue to dye. Last week, a team from Chennai visited and sealed few units after they found that they were still dyeing," says Kandaswamy.

Still, it is only a matter of time before these, too, are shut down, leaving the nation to simultaneously cheer the dismally few successful interventions to protect and preserve the environment and human lives, while lamenting the death of an industry with much financial promise.

article