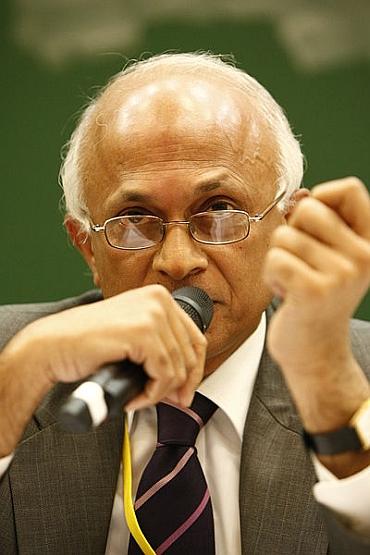

Photographs: Reuters Ranjan Mathai

India's Foreign Secretary Ranjan Mathai listed out some economic policies that emerging nations, particularly India, must adopt to keep them from driving off the growth path and also spoke about how these policies are closely linked with the nations' foreign policy.

He was addressing a conference on 'Economic Policies for Emerging Economies' in New Delhi. Following is the text of his speech:

During the deliberations today you may have dealt with definitional issues in the context of the emergence of 'emerging economies', and just how many economies fit the description.

It is, therefore, not my intention to go back to the Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper Number 66, which brought BRICS into the jargon of international discourse.

But the last ten years have propelled BRICS further forward in popular imagination, as well as in the reality of their contribution to the global economy.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

Obviously Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey and some other countries may need to be added to the acronym. Or, just as we have IBSA, we could have further sets of emerging economies who acquire prominence when grouped together.

Such groupings are arbitrary as the emerging economies are not necessarily cohesive. But collectively or severally, the emerging economies are set to become poles of economic and political power in a multi-polar world.

Such predictions are by nature dangerous. In the 1960s, Herman Kahn had more or less convinced some that by the end of the century we would all need to speak Japanese to survive.

There are other examples to show that: In the long run not only are we all dead, but all our predictions too are dead!

Now the Financial Times of December 7 carried the headline, 'Brazil growth shudders to halt'. The article suggests a somewhat eager anticipation of a hard landing or slowdown for all four BRICS countries.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

Some slowing may be inevitable over time but to draw a conclusion that the long-term trends are negative is probably a case of premature schadenfreude. However, policies have clearly to be set in place if the trend lines are to stay steady.

Evidence from the growth path of China and India shows that there are some key features of the economic environment that are necessary to sustain such growth and, hence, good pointers to the economic policies necessary:

1. The liberal, open economic order built over the last 60 years with stable trading rules, a reliable international reserve currency, protected commons through which merchandise and invisibles can be exchanged globally, has been identified by Ashley Tellis as a key enabler.

2. India's case is not one of trade-driven growth. But the unleashing of animal spirits, which has enabled us to leverage a 34 per cent savings rate, is not purely a domestically driven mechanism.

The success stories of Indian software professionals were made possible through integration in global communication networks and the relatively open system of trading in services.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

Global success of the services sector imparted new imagination and confidence to our country, apart from financing a boom in domestic consumption, and creating a wider domestic consensus on the benefits of participation in the global economy.

Emerging countries would, therefore, do well to play their part in preserving the viability of global regimes and systems of trade and transport, tweaking them to remove distortions which deliberately work against them.

But individually, or as a group, emerging economies must encourage greater emphasis on trade and connectivity.

A second critical area is the policies that affect our energy choices. There is no getting away from the fact that even today sustained growth will require what Lenin called 'electrifizia'.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

With 40 per cent of the population still without access to commercial energy in India one of the greatest challenges of economic policy is to stimulate energy investments, efficiencies and innovations

As the recent Durban discussions showed, there will be continued pressure to slow down the emergence of emerging countries, through mechanisms of legally binding agreements which would curtail critical energy and infrastructure development.

In our own interest, as much as in our responsibility for the planet, emerging economies have no alternative but to become Green-focussed economies within one generation.

This will call for a technological revolution, which points to another set of economic policies necessary.

Emerging economies will have to take account of the fact that their spectacular growth in the last 2-3 decades began at low levels of development. Most had resources that remained underemployed because of lack of opportunities or lack of what Tellis calls 'catalysing mechanisms'.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

Economic reform helped with factor accumulation, and at the same time the emerging economies benefited from the 'late industrialisation' syndrome of using production techniques, technologies and processes already tried and tested elsewhere.

In telecom, for example, we were able to leapfrog an entire stage of development and did not have to dig up the whole country with copper wire for a nationwide landline network before moving as we have to a stage where over 800 million people have telecom connectivity.

The future will depend to a much greater extent on productivity. Of course, availability of capital, technology, higher education and efficient infrastructure will be necessary.

But as an Asian Development Bank (ADB) study looking at the year 2030 notes 'what will differentiate countries is their ability to adopt technologies -- the skill level of workforce, appropriate capital and infrastructure, openness to trade and FDI, and more generally the investment climate'.

The so-called demographic dividend can be one only if productivity gains become the norm. Economic policy that drives such productivity improvements, would give us balance in the terms of engagement with countries and organisations which are major sources of technology and finance.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

Any historical overview will also clarify that economic policies cannot be divorced from the existing political realities of the world.

To have freedom and space for economic policy-making that seeks to increase participation in the global economy, it will be necessary for the emerging economies to have increased weightage in the global political discourse, and in the management of the global commons.

The ability to pull our weight in reformed institutions of global governance (including international financial institutions), a visible capacity for self-defence with domestic capabilities in the requisite technologies, and diplomatic skills would all be essential.

We have to manage the interface of economic and politico-military assets, all the while articulating policy and interests in a world of instant communication.

The economic policies of emerging countries will have to take into account the political balance in the world and make choices which are best suited for navigating a sustainable course in this complicated scenario.

. . .

What India must do to keep its economy BOOMING

Photographs: Reuters

As we see it in South Block, our economic policies must enable us to build on India's inherent strengths and factor advantages.

All development is ultimately local. But our potential is best leveraged through structures of international cooperation.

The G-20 provides the emerging economies one platform which is shared with the established powers, whereas IBSA, BRICS or even the G-77 provide avenues for beneficial convergence with other emerging economies and beyond.

In many areas, partnerships and the task of finding interlocutors will be between institutions, corporates and organisations, not necessarily between countries.

Managing such kaleidoscopic variations will not be easy, but they would be essential part of economic policy-making just as much as in foreign policy.

Ranjan Mathai is India's Foreign Secretary.

article