| « Back to article | Print this article |

What ails the public sector banks

Every now and then exhortations are made, including in this newspaper, that the government should further reduce its equity stake in public sector banks.

The basic logic is that public sector banks are uncompetitive because of the government’s implicit guarantee.

Further, the inefficient maturity transformation practices of public sector banks have resulted in their accumulating 86 per cent of the non-performing assets of the banking sector compared to their asset base of 75 per cent.

Consequently, the government has been compelled to periodically recapitalise public sector banks and has provided between Rs 10,000 crore (Rs 100 billion) and Rs 20,000 crore (Rs 200 billion) in each of the last three years, funding that it can scarce afford given the need for fiscal stringency.

This article examines the call for the government to reduce its majority ownership in public sector banks ostensibly with the objective of improving the functioning of these banks.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

What ails the public sector banks

In the last 10 years, there have been many high-profile cases in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in which private banks and companies, including US automobile behemoths, have sought and received government assistance.

In India, the wrongdoing of Global Trust Bank and Satyam comes to mind. Public memory can be short even in well-publicised cases.

The 1992 Harshad Mehta scam involved Indian and foreign private banks, which were guilty of illegally funding a huge run up in the stock prices.

It is inconceivable that public sector banks and private banks or the business community were unaware that the boom in stock prices was due to market manipulation and hence unsustainable.

The book by economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time is Different, details the involvement of private banks in financial sector disasters around the world over the centuries.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

What ails the public sector banks

Clearly, private ownership is not a necessary or sufficient condition to ensure competitive efficiency in risk taking.

In India, financial institutions and public financial institutions were set up under Acts of Parliament to promote investment in industrial and infrastructure projects.

For several decades after independence, financial institutions and public financial institutions received funding at concessional rates from the Reserve Bank of India and the government.

Over time, subsidised funding dried up and these institutions became more dependent on bond funding.

Gradually, the two categories were lumped together and referred to as development finance institutions.

DFIs continue to find it difficult to access bond funding since long-term debt markets are underdeveloped in India.

The distinctions between DFIs and banks have also blurred with time after ICICI, which was initially a DFI, became a private sector bank through a reverse merger and the Industrial Development Bank of India did the same to become a public sector bank.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

What ails the public sector banks

As for other categories of financial institutions, cooperative banks have fallen in the past between regulatory stools, as happened in the Madhavpura Mercantile Cooperative Bank scam.

Although the RBI has tightened its supervision, the registration of such banks as co-operative societies dilutes their accountability.

Another example of what is anomalous in our banking sector is the National Housing Bank, which was set up under an Act in 1987.

It is not clear what impact the NHB has on the housing finance sector or why it continues to be owned by the RBI and headquartered in Delhi instead of Mumbai, which is the financial capital.

The government’s equity stake in the largest public sector bank, namely State Bank of India, is about 62 per cent compared to 69 per cent in the fossil fuel major Oil and Natural Gas Corporation.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

What ails the public sector banks

The government owns 72 per cent in IDBI; 56 per cent in the Industrial Finance Corporation of India, even after the IFCI Act was repealed in 1993; 67 per cent in BHEL; 75 per cent in NTPC; and 90 per cent in Coal India.

These numbers are probably understated since government-owned Life Insurance Corporation of India, DFIs, state finance corporations and state industrial development corporations own stock in both government and privately owned banks and firms.

LIC holds long-dated government debt securities in its investment portfolio.

This is logical, given the requirement of regular outflows on policies that mature. However, as LIC is owned by the government, it is sub-optimal for it to invest in the shares of government-owned institutions.

There is little diversification of risk and its policyholders are not well served in terms of rates of return by investment decisions, which are often based on political economy factors.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

What ails the public sector banks

As the cross-holding linkages across government-owned banks, financial institutions and public sector undertakings are unclear, the government would do well to detail the extent of its direct and indirect ownership in all majority government-owned institutions on publicly accessible websites.

Next, the objective for reforms should be to target the lower-hanging fruit.

That is, act on what is achievable in incremental steps.

For instance, dilution of the government’s stake in SBI and other public sector banks can wait since the government’s stake cannot be reduced below 50 per cent without amending the Acts concerned.

This is relevant in according priority to the various tasks that confront the government in the four months left till the next general elections in April-May 2014.

According to press reports, the finance ministry informed the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs recently that cancellation of the allotment of 62 coal blocks would lead to an increase in NPAs of about Rs 1 lakh crore (Rs 1 trillion).

This comes at a time when NPAs have gone up sharply in the last 12 months.

Public sector banks would be among the banks that would be hit hard.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

What ails the public sector banks

It was separately reported that the government proposes to use proceeds from disinvesting in PSUs to fund the recapitalisation of public sector banks.

This is too close for comfort to the proverbial robbing of Peter to pay Paul.

A better move would be to get PSUs to reinvest in improving their information systems and for the government to make the selection of their CEOs timely and transparent.

More importantly, attention needs to be focused on reducing the government’s equity stake in Coal India and LIC sooner than in public sector banks.

To conclude, the RBI is in the process of issuing licences for new private sector banks. Every effort needs to be made to get these new banks up and running to enhance competition and increase longer-term lending.

Of course, entry of new private banks will not level the field between public sector banks and private banks.

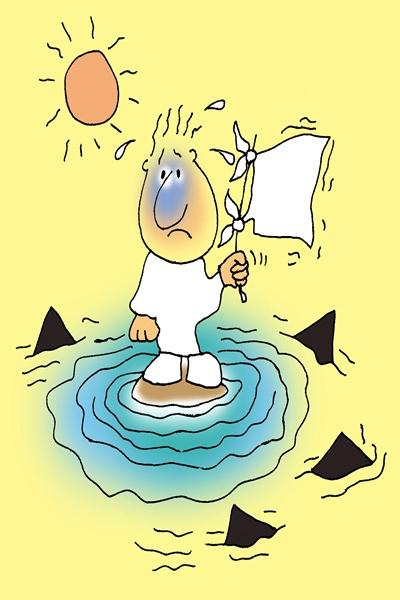

Public sector banks will continue to benefit from the government’s guarantee umbrella. At the same time, public sector banks are saddled with large numbers of inadequately trained or demotivated personnel who cannot be retrenched.

Jaimini Bhagwati, a former Indian high commissioner to the UK and finance professional in the World Bank Treasury and the finance ministry, is RBI chair professor at Icrier in New Delhi.