| « Back to article | Print this article |

Is the Indian family back in business?

The overall trend to professionalise has always seen an upward trajectory, but at varying rates of adoption.

If you buy the theory that N R Narayana Murthy is returning to what essentially is a 'family businesses', a question worth asking is if the trend of eschewing an outside professional for a 'family' member to lead and often resuscitate a company is in its ascendancy.

After all, in the 1990s, the mantra in Indian business was 'professionalise or die'. The reasons were logical. For example, making a business decision to sell a loss-making entity within a group company that was under the helm of another family member could generate enormous headaches.

Plus, family members didn't necessarily have the managerial chops to run their outfits which often demanded new and specific skill sets that were constantly evolving.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Indian family back in business?

This required outsiders. "Family owners realise that talent is a big problem," says Pramath Sinha, founding dean of Hyderabad-based Indian School of Business (ISB). "Most business owners today think, 'to attract talent I have to professionalise' since analysts and consultants also keep telling them this," he adds.

Today, not only is the landscape awash with professionals, most family businesses say they swear by them.

Nearly seven in 10 respondents of family-run businesses in a 2012 Dun and Bradstreet study indicated that they preferred hiring independent professional managers for leadership roles rather than their relatives. Just 15 per cent of those questioned indicated a preference for leaders from within the family.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Indian family back in business?

The overall trend to professionalise has always seen an upward trajectory, but at varying rates of adoption. At first, the yoke of colonialism ensured that Indian businesses grew very slowly.

Even when Prakash Tandon became the first Indian chairman of Hindustan Levers, there were probably no more than 40 managers in all of India, says Dwijendra Tripathi, author of The Oxford History of Indian Business.

Today, a large number of family concerns - comprising around 70 per cent of businesses in India - have professionals at their helm.

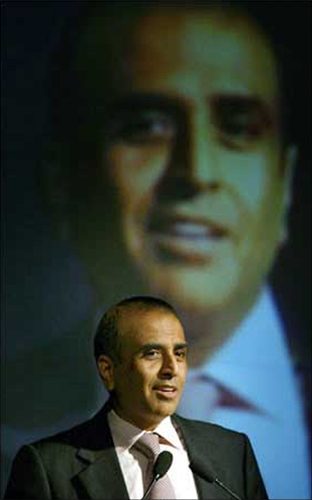

Bharti Airtel, for instance, has Gopal Vittal, a marketing expert brought in by Sunil Mittal, to revive his telecom company. Spicejet has Neil Mills. Tata Motors has Karl Slym. Godrej Consumer Products has Vivek Gambhir.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Indian family back in business?

Future generations are also jockeying - or being positioned - for their share of the pie. Retailer Kishore Biyani's daughter Ashni is a director in her father's company, while Mukesh Ambani is likely to induct his children into Reliance Industries. This isn't all that irrational an impulse.

"If your great-grandfather, grandfather and father have run the company, you have a justifiable right to want to have a shot at doing so too," says ISB's Sinha.

In other words, it seems the family hasn't really gone away. Is that a good thing? On one hand an umbilical cord attached to a business that has been around for generations suggests that business decisions will not be taken flippantly. But many don't think so.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Indian family back in business?

"Any deviation from professionalisation takes away from value for the shareholder," says Sebastian Morris, professor of strategy at the Indian Institute of Management-Ahmedabad, who also thinks, in general, minority shareholders are exploited in India and not given their due.

Still, family concerns will thrive in late industrialising countries like India for a while, says Morris, for a number of reasons.

As long as public sector banks continue to shell out the preponderance of loans given in the country, connections to politicians who can influence these banks will allow business families to play an important role.

Similarly, land allotments to industry by the state will continue to incentivise the family role.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Indian family back in business?

That said, the role of the family has a limited shelf life in the long run, says business historian Tripathi, and the reason is simple.

"As businesses increase in size and complexity, you need more money from capital markets, more competence and more professional people involved," he says. "It becomes an international concern and not just a family concern."

Family splits - there were 30 between 1970 and 1992 and 70 between 1970 and 2005- are now pervasive, heralding the disintegration of the joint family system, which was the glue that used to bind most family businesses.

In another 50 years, says Tripathi, the family business will be approaching extinction and that there will be a growing trend of owners being unable dictate terms to professionals.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Indian family back in business?

But for now, 'fixing' using contacts instead of running a business through strategy and good management practices is the need of the day in India, says IIM's Morris and this is evident in industries ranging from textiles to power.

Plus, business owners are not yet fully accustomed to relinquishing their companies to professionals like Dabur has done. "It's like dating versus marriage," says Sinha. "You like the idea of bringing in professionals, but when you start, it doesn't seem very likeable anymore," he adds.

Only once the economy deepens and business owners realise they don't have the specialised skills to run things will there be an inflection point. Till then, the Indian family owner is here to stay.