| « Back to article | Print this article |

Govt plans to 'promote' GM food rather than regulate it

The Biotechnology Regulatory Authority of India Bill in the current form sides with the companies in genetically modified business rather than ensuring safety of these foods, writes Kavitha Kuruganti.

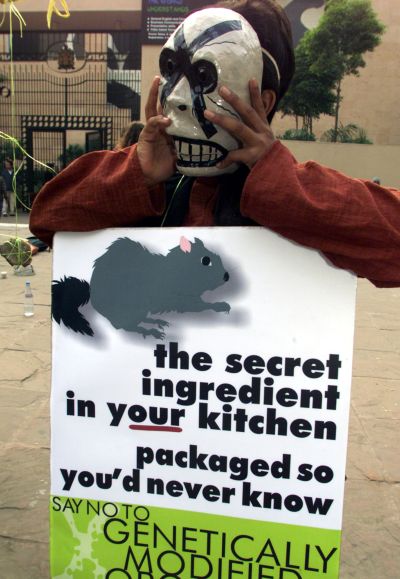

The controversy around genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in our food and farming rages on with claims and counterclaims emerging constantly.

Do we need GMOs? Are they safe? Do they permit sustainable use of resources? Will they uphold farmers' rights over seed resources and lead to viable livelihoods? Would they imply trade security?

In India, we do not have an express statute to regulate GMOs. Currently, the Environment Protection Act (EPA)'s 1989 rules govern the regulation of this controversial technology.

The government is now proposing a single-window, fast-track clearance system in the form of a Biotechnology Regulatory Authority to be set up through a statutory framework.

A Bill called the Biotechnology Regulatory Authority of India (BRAI) Bill, 2013, was tabled in the Lok Sabha on April 22, 2013 by the minister for science & technology.

The proposed Biotechnology Regulatory Authority will have just a handful of technocrats taking all the decisions, whereas the current apex regulator, the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee, is a multi-ministerial body representing various interests.

Click NEXT to read more…

Govt plans to 'promote' GM food rather than regulate it

Moreover, the objective of the Bill is to "promote" the safe use of modern biotechnology, which is a serious distortion of the very need for regulation in this sphere.

The technology is already being promoted through existing policies and schemes related to the research & development on GMOs.

The fact that the ministry of science & technology (a promotional ministry) proposes to house the regulator is an objectionable conflict of interest.

Another matter to note is that this Bill has been proposed because of India's commitments in the Convention on Biological Diversity. The nodal ministry in this case is the ministry of environment & forests, not science & technology.

The Bill ignores the fact that the need for regulation of modern biotechnology arises because of the many acknowledged risks associated with this living, irreversible technology - and that the mandate for protecting biosafety lies with the ministries for environment & forests and for health & family welfare.

The 1989 rules of the EPA, for instance, have been created with a "view to protect our health, environment and nature from risks of GMOs".

Click NEXT to read more…

Govt plans to 'promote' GM food rather than regulate it

There is a large body of independent scientific evidence that showcases the numerous adverse implications of GMOs.

The Bt brinjal episode, where the government acknowledged the many lacunae in its initial clearance, has highlighted many more reasons to distinguish regulation from promotion.

In this context, there is no justification for the government to make "promotion" - safe or otherwise - the objective of this Bill, moving away from the current protective regulatory approach.

Apart from the faulty objective, the BRAI Bill has other problematic clauses. For instance, through an "expediency clause", the Union government proposes to take under its control regulation "in public interest", denying any decision-making space for state governments, other than an advisory role.

A clause related to Confidential Commercial Information seeks to bypass the Right To Information Act, 2005, despite Supreme Court orders in the past that brought all biosafety data of Bt brinjal into the public domain.

In the BRAI Bill, regulation is seen as only a technical affair, neglecting the fact that GMOs have implications beyond biosafety.

Click NEXT to read more…

Govt plans to 'promote' GM food rather than regulate it

There is no provision for an assessment of needs or alternatives nor independent or long-term testing.

The narrow, centralised decision-making mechanisms (three full-time and two part-time technical experts constituting the Authority) are a cause for worry, with an additional clause that says no proceeding shall be invalidated by any vacancy in the Authority!

There are no mandatory public consultations built in, despite India being a signatory to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, which has an Article on this.

In fact, most of the problematic aspects of the Bill can be traced back to the "promotion" objective and not the "protection" objective for regulation.

For instance, the expediency clause in this Bill stands in stark contrast to other regulatory bills in the agriculture sector.

Click NEXT to read more…

Govt plans to 'promote' GM food rather than regulate it

In its unanimous report to the Parliament in August 2012, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Agriculture, which studied the earlier version of the BRAI Bill, said: "The government has been for some years now toying with the idea of a Biotechnology Regulatory Authority. The Committee feels that regulating biotechnology is too small a focus in the vast canvas of biodiversity, environment, human and livestock health, etc. and a multitude of other such related issues. [It has], therefore, already recommended… setting up of an all encompassing Bio-safety Authority through an Act of Parliament, which is extensively discussed and debated amongst all stakeholders, before acquiring shape of the law…".

The latest curious twist to this Bill is that it has been referred to the Department Related Standing Committee on Science and Technology, Environment and Forests.

This despite the science & technology minister's recommendation that this Bill be referred to a joint committee of both Houses in response to a growing demand for its withdrawal, to be replaced by a Biosafety Protection Bill and in acknowledgement of the fact that this Bill spans issues beyond science and technology.

The committee has set a deadline of 30 days for public feedback and civil society groups around the country are asking the committee to extend the deadline.

Click NEXT to read more…

Govt plans to 'promote' GM food rather than regulate it

The Bt brinjal episode in India saw some improvements in India's regulatory decision-making, even if they were made in a specific, narrow context.

The government's moratorium was based on views and analysis gathered from a large cross section of society.

One witnessed transparency with biosafety data, public participation, upholding of federal spirit, emphasis on independent analysis and need for independent long-term testing, questioning of the very need for a given GM product and so on. The BRAI Bill, however, seeks to undo all of this.

The government needs to withdraw the BRAI Bill and bring in a Biosafety Protection Bill, through the ministry of environment & forests.

The M S Swaminathan-led Task Force on Agricultural Biotechnology (2004), that was accepted by the government, said the bottom line for regulatory policy should be: "the safety of the environment, the well-being of farming families, the ecological and economic sustainability of farming systems, the health and nutrition security of consumers, safeguarding of home and external trade and the biosecurity of the nation".

The BRAI Bill should follow that broad philosophy too.

The author is a National Convenor of Alliance for Sustainable & Holistic Agriculture (ASHA), an informal advocacy platform of more than 400 organisations drawn from 20 states of India.