| « Back to article | Print this article |

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

Belgium has been without a government for a record 450 days but has managed to grow all the same.

Can the absence of government be a boon?

The term 'anarchy' tends to be associated with war-torn nations in lawless parts of the developing world, rather than the genteel, waffle-scented environs of a prosperous western European country like Belgium.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

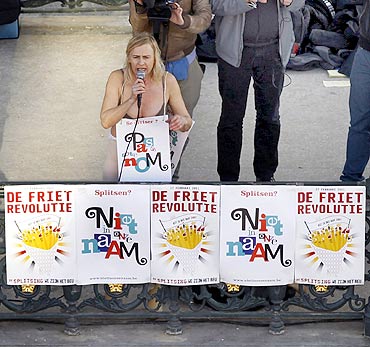

Yet, taken in its literal sense of the absence of government, Belgium -- which has been unable to form a government for over 450 days (a world record) -- is as anarchic as it gets.

And on the surface it appears to present a decent case for the benefits of anarchy at a time when some would argue that governments all over Europe are fighting debt and deficit fires by measures that only fan the flames.

The effects of the draconian austerity measures and tax hikes on which Germany has insisted as the solution to the ongoing eurozone financial crisis are being felt across the continent with growth slowing down and unemployment on the rise.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

The latest data for the second quarter of 2011 exposes a Europe perilously close to recession with the UK's economy crawling up at 0.2 per cent, economic heavyweight Germany faring even worse at 0.1 per cent and France standing still at 0.0 per cent.

In this sorry league table, government-less Belgium is a surprising high ranker with a relatively sprightly growth rate of 0.7 per cent.

An argument that can be made to explain this anomaly is the fact that in the absence of a government, Brussels has been unable to slash spending unlike many of its neighbours, with the result that its economy has so far been sheltered from the strangulating effects of austerity.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

Moreover, away from the macro-economic data, a heavily regionally-devolved power structure means that in Belgium everyday life is scarcely ruffled by the absence of a central government.

The primary dispute in this tiny country of 10 million people pivots on a linguistic and geographical divide between the rich Dutch-speaking region of Flanders in the north, and the poorer French-speaking region of Wallonia in the south.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

The long extant animosity between the two has led to a steady devolution of powers to regional authorities over the decades, which have achieved self-rule in everything from urban development, environment, agriculture, employment, and energy to culture and sports.

As a result, while politicians spend hundreds of fruitless days wrangling over arcane minutiae like the boundaries of certain voting districts, the garbage gets collected on time, the post arrives everyday and the average Belgian is able to enjoy her afternoon waffle and coffee with little sense of crisis.

In fact, the country managed the whole of its six-month presidency of the European Union last year with a caretaker government.

Click NEXT to read further. .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

Most Belgians appear to think of their non-governmental state as an exasperating but also amusing national quirk, rather than a major hindrance of any kind.

In many ways, Belgium has emerged as the poster child of a post-modern state where it is the sub-national (Flanders and Wallonia) and the supra-national (the European Union that is headquartered in Brussels) levels of administration that matter more than the national government.

That said, while no decisions might be better than 'bad' decisions, libertarians should probably pause before rushing to adopt the Manneken Pis as their new mascot.

The sustainability of Belgium's growth in the medium term without serious reform of the kind a caretaker government cannot carry out remains suspect.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

The country's public debt is just short of 100 per cent of its GDP.

And the ongoing political stalemate has investors on edge with the result that Belgian bond prices have been volatile.

The spread between 10-year Belgian and benchmark German bonds -- a key indicator of investor confidence -- has spiked to record highs several times in the last few months.

Some of the country's buoyancy is, in fact, explained by the policy of indexation by which salaries, pensions and unemployment benefits are indexed to inflation, automatically rising in concert with prices.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

The European Union has been urging Brussels to abandon indexation, warning that it risks exacerbating the effects of inflation.

Belgium's 450-plus-days sans a government are also a sad commentary on the ability, or lack thereof, of modern European states to handle diversity.

The intransigence of both the Dutch-speaking northerners and their French-speaking southern compatriots has led to a stalemate that is worse than the one that saw post-war Iraq struggle to form a government for 250 days.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

The main point of contention turns on the fact that the country's welfare system is federally funded, which in practice means that Flanders pays for Wallonia's pensions and health care.

Flemish politicians want to end fiscal transfers from north to south, something the socialists in the south resolutely oppose.

Belgium's anarchy, thus, exemplifies in miniature a problem that plagues the European Union as a whole, indicating how difficult resolving the eurozone's woes will be given the cultural gulf between north and south Europe.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Special: Can the absence of government be a boon?

Even within a single country, large-scale transfers of wealth from north to south are so deeply unpopular that they threaten the dissolution of the nation.

But if the Flemish find it impossible to aid their own compatriots, expecting Germany and its fiscally conservative northern neighbours to keep coughing up for the debts of Greece and its fellow Club-Med nations is unrealistic.

Clearly, while anarchy may be benefiting Belgium in the short term, its long-term effects are likely to be less benign.