| « Back to article | Print this article |

After the financial crisis, India has a ray of hope

Continuing US quantitative expansion will make for continued inflows of portfolio investment - which will shore up the stock market and the balance of payments, keeping currency turmoil at bay, says Subir Roy.

Five years after the 2008 global financial crisis plunged the world into the Great Recession, there is a ray of hope that may lead the world into quicker recovery than what has happened till now.

This is important for India, since its economy and business confidence – from stock market sentiment to exports to overall growth – are increasingly dependent on what happens in the rest of the world.

The economic orthodoxy of a quarter-century may have to give way in the face of mounting evidence on the ground; and another orthodoxy, earlier discarded, may be reinstated.

Policymakers are increasingly moving towards the notion that inflation is not an absolute no-no - that, in fact, inflation can be quite desirable in small doses to propel recovery.

Click NEXT to read more…

After the financial crisis, India has a ray of hope

What’s more, that discarded Keynesian policy instrument, a fiscal stimulus, may emerge as the policy imperative.

The most recent development in this regard is not just the United States but also the International Monetary Fund (IMF) taking Germany to task over that country’s excessively high trade surplus, which is standing in the way of beleaguered European economies being able to set right their own negative balances.

Germans, long considered a model of thrift, are being asked to consume more through higher government spending (minimum wages, infrastructure) so that this adds to European demand and enables definitive recovery.

This comes after the Bank of Japan has indicated that it will go on pursuing its revolutionary easy money policy in an attempt to take inflation up from 0.7 per cent to the targeted 1.9 per cent in 2015, so as to stamp out deflation and achieve growth of 1.5 per cent.

Click NEXT to read more…

After the financial crisis, India has a ray of hope

This is part of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s policy of jolting the economy forward with the help of fiscal and monetary stimulus to end the stagnation of two decades.

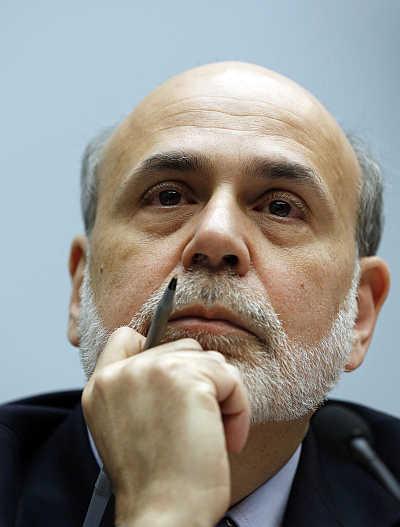

A little earlier, the US president had nominated Janet Yellen, a dyed-in-the-wool monetary dove, to succeed Ben Bernanke as the head of the US Federal Reserve. This is seen as a reversal of what presidents had done earlier by bringing in Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan to send out the right signals and bring down inflation.

Once confirmed in the position, she can be expected to continue with quantitative expansion, now in its third incarnation, until such time as US unemployment goes down to 6.5 per cent. Intellectually, she has in the past struck a different posture from the single-minded pursuit of low inflation, implying that she was also concerned about employment and growth.

Why is all this happening? After 2008, developed economies adopted both vigorous monetary and fiscal stimulus to address the recession, and this bore quick fruit in 2010.

But it is now widely recognised that in country after country the stimulus was withdrawn too quickly, leading to anaemic recovery or none at all.

After the financial crisis, India has a ray of hope

Overall, the IMF sees a deflationary bias in Europe and the world. The US is recovering and emerging market economies, though they are growing at a slower rate, are all right - but European recovery has been a long time coming.

It is not worried about US inflation, which has remained persistently below the Fed’s target of two per cent since 2008. It finds that fiscal consolidation in the US has been far too strong.

Most significantly, quantitative expansion (the Fed’s $85-billion monthly purchases of Treasury bonds) has not fuelled inflation.

This has proved wrong the bond vigilantes, who had feared that monetary expansion would lead to inflation, rising interest rates and a collapse in bond prices. None of this has happened.

In fact, in these uncertain times, money has flowed into the US, making it easy for the Fed to dictate extremely low rates.

Click NEXT to read more...

After the financial crisis, India has a ray of hope

With the greater danger in the US and Europe still being deflation and the persistent theme being that a little bit of inflation is good, there is a need for fiscal stimulus – monetary stimulus cannot go on forever – that works powerfully through the multiplier, leading to a quick revival in demand, growth and jobs.

It is fascinating that Germany, the paragon of austerity, is being asked to get rid of some of it and the IMF realises that austerity has crimped growth much more than expected.

All this gives India a bit more breathing space. Continuing US quantitative expansion will make for continued inflows of portfolio investment - which will shore up the stock market and the balance of payments, keeping currency turmoil at bay.

This will allow a bit of time for inflation to be brought under control by addressing supply issues.

If, as a result of the old Keynesian economics becoming respectable again, developed economies grow faster, that will be good news for Indian exports too. A win-win scenario!