| « Back to article | Print this article |

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Within days of Morgan Stanley and StanChart revising downwards India's growth forecasts for the current fiscal, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America-Merrill Lynch on Friday steeply scaled down their gross domestic product estimates for India to 6.6 per cent and 6.5 per cent respectively for 2012-13.

These two revisions are the lowest forecasts yet, as the projection of Morgan Stanley is 6.8 per cent while that of StanChart is at 7.1 per cent, and are drastically lower than the government forecast of 7.6 per cent.

So why is India in such a mess?

Click on NEXT to find out...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

One: Inflation Monster

The single biggest failure of the second United Progressive Alliance government has been its inability to control inflation in general and food inflation in particular. Food prices, as measured by the official wholesale price index, have gone up at a faster pace over the last three years than they did in the five years of the first UPA government.

Inflation adversely impacts the poor more than the rich or the middle classes and results in an indirect transfer of resources from the worse-off to the better-off sections of the population. When inflation is driven by high food prices as it has in India in recent years, the deleterious consequences are magnified since the economically underprivileged spend half or more of their incomes on food.

Food inflation has not merely immiserised the poor and sharply eroded the real incomes of middle class families -- it has widened inequalities between the affluent and the indigent. The rich has certainly got richer. And even if the poor may not have got poorer, the gap between the rich and the poor has certainly widened contributing to social tensions.

Whereas cereal prices have not gone up relatively, the increases in the prices of vegetables, fruits, milk and dairy products have been particularly steep. Inflation has had a negative impact on household savings and slowed down the demand for consumer durables and industrial products.

Click on NEXT for more...10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Two: Ineffective Monetary Policies

To treat the problem of inflation as largely a monetary policy issue and by placing a great onus on the Reserve Bank of India to curb inflation by containing liquidity, the government has simplistically followed textbook notions of checking "too much money chasing too few goods". Food inflation has been primarily driven by supply constraints.

The mismatches between demand and supply have worsened on account of inadequate coordination between different ministries (Commerce, Finance, Agriculture, Food and Consumer Affairs) to balance the needs of exporters and the domestic market, causing spikes in the prices of particular food products like sugar, onions and pulses.

Thus, by tightening liquidity, the RBI has had to perforce harden interest rates, which, in turn, has contributed to a slowdown of investments in industry and capital formation. The dip in the index of industrial production has exacerbated the phenomenon of "jobless growth" in the country, even as the government has remained singularly obsessed with stepping up the rate of growth of gross domestic product (GDP) and not with ensuring equitable distribution of the benefits of economic growth.

Click on NEXT for more...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Three: Weakening Rupee

The depreciation in the value of the Indian rupee vis-a-vis the US dollar is a consequence not only of external factors but also of the country's imports growing faster than exports resulting in the trade deficit jumping by 56 per cent between 2010-11 and 2011-12.

The deficit has sharply widened because imports - more than half of the country's import bill is accounted for by two items, crude oil and gold - are inelastic and export growth has been sluggish. India's export markets in the West have disappeared or shrunk drastically on account of the Great Recession while many of the country's exportable products are still not sufficiently competitive in Asian markets (despite the recent depreciation).

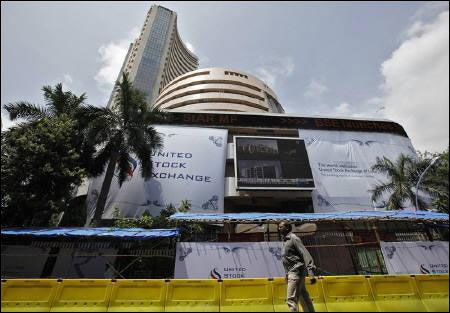

The fall in the external value of the rupee by a fifth over the last year has contributed to foreign institutional investors shying away from stock exchanges (leading to the decline in share indices) and foreign direct investors repatriating larger amounts to their home countries, even as domestic industrialists prefer to invest outside India rather than at home.

The higher rupee value of imported petroleum - India currently imports 80 per cent of the country's total requirements of crude oil - is adding to inflationary pressures.

Click on NEXT for more...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Four: Oily Mess

The country's petroleum sector is in a state of chaos. It is claimed that petrol prices have been decontrolled but public sector oil refining and marketing companies like Indian Oil Corporation do not increase prices without a nod from the government.

Otherwise, how does one explain the sudden one-shot increase of Rs 7.50 in the retail price of each litre of petrol on May 23 when oil companies could have gradually increased petrol prices over the last five months? With the gap between petrol and diesel prices rising and with the government unwilling to increase excise duties on diesel cars, sales of diesel cars continue to shoot up adding to urban pollution and wastage of subsidies.

Meanwhile, the adulteration of kerosene with other petroleum products continues to be rampant. The government does not want to give up its shares of taxes from the petroleum industry and oil companies persist in paying dividends and showing profits on their books of account while complaining loudly about "under-recoveries" on account of subsidized sales of diesel, cooking gas and kerosene. What a slippery slope?

Click on NEXT for more...10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Five: Crony Capitalism

The ugly underbelly of the policies of economic liberalisation followed over the last two decades has been crony capitalism at its worst. The most prominent of Indian industrialists have emulated some of the worst practices of Russian and Chinese oligarchs in the manner in which they have successfully influenced government policies and systematically subverted the rule of law.

One example will illustrate this contention. There are at present seven mobile phones for every ten citizens - and more phone subscribers than human beings in most urban areas - in a country where there used to be one phone for every thousand individuals as recently as 1997, three years after the government gave up its monopoly over the telecommunications sector.

This is also the same sector which has witnessed the biggest scandal in independent India (and perhaps in the world) on account of misallocation and undervaluation of scarce electro-magnetic spectrum that may have resulted in a "presumptive" or "notional" loss of close to US$ 40 billion to the exchequer, according to the Comptroller & Auditor General of India.

Even as official policies continue to marginalize public sector corporations (witness the current state of Air India and Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited, to name only two), powerful lobbies of private industrialists continue to exert an influence on government decisions.

Contracts are tailored to benefit private companies at the expense of government organizations, an example being the natural gas exploration contracts relating to Reliance Industries Limited and the Oil & Natural Gas Corporation.

Click on NEXT for more...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Six: Misutilisation of Natural Resources

The second-generation (2G) spectrum scam epitomizes the manner in which the Union government, which is supposed to act as a custodian of natural resources that belong to the people of the country, has failed to perform its functions in a prudential and impartial manner.

Instead of ensuring transparency in the manner in which natural resources are valued and allocated, government policies have been opaque and less than fair resulting in a plethora of allegations of corruption and nepotism.

From coal and natural gas to iron ore and telecom spectrum, from the manipulation of land use laws by Adarsh Housing Society in south Mumbai to the way in which the Commonwealth Games were conducted in New Delhi, those in positions of power have brazenly sought to cover up acts of abuse of discretionary authority and illegal appropriation of rents.

The issue of land acquisition by private industry for non-agricultural purposes - for digging up coal or for setting up special economic zones for export-oriented industries -- remains highly contentious and deeply divisive.

Click on NEXT for more...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Seven: Reluctant Regulation

The misutilisation of natural resources has been facilitated by reluctant regulators, who were typically former bureaucrats and who were often selected for their subservience to their political masters. From financial markets to electricity distribution, the government did not deliberately empower regulatory authorities in the wake of economic liberalisation thereby offering wide windows of opportunity to crony capitalists to milk the system and earn super-normal windfall gains. The regulatory bodies became sinecures to park loyal babus after they retired.

The government did away with the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission with alacrity but failed to expeditiously empower the Competition Commission that could check abuses of market dominance.

The Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board is another example of a body that has been consciously rendered toothless and made a fringe player.

Click on NEXT for more...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Eight: Politics-Crime-Business Nexus

The combination of crony capitalism, reluctant regulation and misutilisation of natural resources has manifested itself in the ugly nexus among corrupt politicians, criminals and businesspersons. No one symbolises this nexus better than Gali Janardhana Reddy, former Minister for Tourism, Infrastructure Development and Youth Affairs in the government of Karnataka led by B.S. Yeddyurappa.

While both have been disgraced and have had to spend time behind bars, they successfully spearheaded the systematic loot of iron ore located in the districts of Bellary in Karnataka and Ananthapur in Andhra Pradesh. Much of the illegally-mined ore was exported to China in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics.

Other examples of the operation of this corrupt nexus can be found in different parts of the country, in Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and Rajasthan, where representatives of the mining mafia rule the roost because of their close association with influential politicians and bureaucrats.

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Nine: Red Corridor

Juxtapose the mineral map of India with maps showing the presence of forest resources, areas where tribals and indigenous communities dominate and zones where left-wing extremism are at their peak, and one will discern the presence of the proverbial 'red corridor' that occupies over a fourth of the country's geographical area from the Himalayan mountains (the Pashupati temple in Nepal) to the Bay of Bengal (not far from the Tirupathi temple). Is it a coincidence that these areas overlap with one another? Certainly not.

India is right now in a vicious cycle in dealing with what Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has time and again described as the country's "biggest internal security threat". We all agree that the Maoist "menace" cannot be treated as a law-and-order problem but one relating to absence of development.

Good officers do not want to serve in these districts. Roads, schools, health-care centres and mobile phone towers are not built because Naxalites don't want them. So these areas remain economically challenged even though on paper, money is shown as being spent. And left-wing extremists gain ground. The vicious cycle goes on.

Click on NEXT for more...

10 reasons why the Indian economy has gone off track

Ten: Political Paralysis

Instead of focusing on reforms for the health-care and education sectors and proper delivery of subsidies to assist the fourth of the country's population whose conditions are worse than those who live in Sub-Saharan Africa, the government has tried to bring about contentious policy changes - such as allowing foreign investments in multi-brand retail outlets - that elude a consensus within the ruling coalition, leave alone the entire political class.

Rather than concentrating its efforts on hiking the cap on foreign investments in insurance companies and allowing pension companies to play the stock markets, the government could have tried much harder to bring about what is arguably the most important economic reform measure, namely, a common goods and services tax across the country's 28 states and seven Union territories that would not just unite India's fragmented market but also reduce corruption by ensuring transparency.

The writer is an independent journalist and educator.