| « Back to article | Print this article |

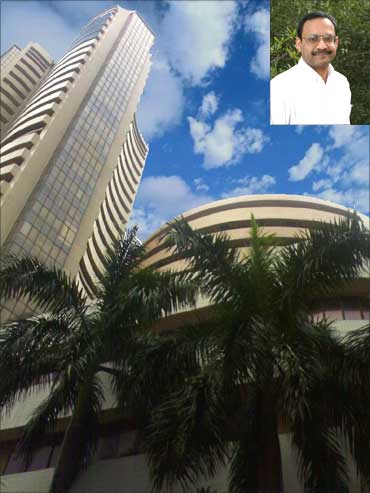

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

In case you think this is the figment of an overactive imagination, think again. Alok Aggarwal, co-founder and chairman of Evalueserve, a leading provider of knowledge services, believes that the Bombay Stock Exchange's 30-share benchmark index, the Sensex, could touch the 50,000-mark by the December 2015.

Here is the explanation for how he reached this conclusion.

January 8, 2008 is considered a golden day in the history of the Indian stock markets as the Sensex touched a record 21,077.53 in intra-day trading. It closed the day at 20,873. Analysts expected the Sensex to touch 25,000 by the end of 2008; some even saw it touching 27,000. But Aggarwal had warned then that "because of a sudden crisis of confidence, there would be a flight of foreign institutional investor (FII) money out of the country".

He pointed out that if $12 billion of FII money was to leave within a quarter, the stock market would drop by approximately 30 per cent to the level of 14,000. By July 8, 2008, Aggarwal's predictions came true. And then the world economy was sucked into the vortex of one of the worst recessions in recent times.

On October 24, the Sensex plunged by 1,070.63 points (10.96 per cent) to close at 8,701.07, and sank further to a low of 8,160 on March 9, 2009. Since then it has climbed gradually to hover very close to the 18,000-mark in April 2010.

Many analysts believe that an inflow of approximately $18.1 billion of FII money into India (during April-October 2009), most of which has went into the Indian stock market, was the primary reason why the Sensex slowly started to move northward.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

Aggarwal says that the Indian stock market, which was grossly overvalued two years ago, is now more reasonably valued, thanks to India's continued economic growth.

If a country's market capitalisation as a proportion of global market capitalisation mirrors its share of world GDP, India's stock market seems to be within 15-20 per cent of where it should be, says Aggarwal.

According to a recent study by Bespoke Investment Group, India's market capitalisation was 2.7 per cent of world market cap, while India accounted for 2.2 per cent of world GDP in 2009. Thus, said Aggarwal, the Sensex and other Indian indices seem to be trading within 10 per cent of where they should be.

"So if the Indian economy continues to grow at an average of 8.5 per cent per year until December 2015, if there is no double-dip recession in developed countries, if the Indian rupee continues to trade around Rs 46 to the US dollar, then the Sensex should be comfortably placed at 15,622 on March 31, 2010, and around 50,130 in December 2015."

The Sensex closed at 17,527 on March 31, 2010.

Similarly, says Aggarwal, BSE-100 should be comfortably placed at 30,247 in December 2015.

He is optimistic that even though the Indian stock markets will continue to be fairly volatile for the next few years, "an investor who takes a long-term -- a five- to six-year -- view is likely to be rewarded very well, especially after taking dividends into account."

The future of Indian stock market, says Aggarwal, is heavily dependent on the following three parameters:

- Future growth of the Indian economy, annual inflation, and productivity related improvements;

- The inflow and outflow of foreign institutional investment; and

- Any movement of price-earnings ratios.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

Future growth of Indian economy

India' economy grew at an annual rate of 9.4 per cent during the three years -- 2005 to 2008 -- with agriculture averaging around 5 per cent per year. India also survived the global meltdown of 2008-09 due to minimal exposure of the financial sector to the sub-prime lending, and domestic demand driven growth.

Aggarwal said that India's average annual growth rate during the two years, 2008-2010, was likely to be around 7 per cent (in real terms), with the current fiscal year outperforming the last one by over one per cent.

Favourable demographics, high savings rate, rising middle class, and underleveraged households suggest that domestic demand, and the economy, will continue to grow strongly.

Taking a long-term view and assuming an exchange rate of Rs 46 to 1 US dollar, an annual growth rate of 7 per cent in 2009-10 and 8.5 per cent during 2010-16, the market sentiment being overly buoyant, an inflation of 6 per cent per year, the size of the Indian economy in nominal terms is likely to be:

- $1.250 trillion in 2009-10,

- $2.400 trillion in 2014-15,

- and $4.640 trillion in 2019-20.

This implies a cumulative nominal annual growth of 14 per cent and an approximate four-fold increase in the coming decade.

During 2009-10:

- The services sector would account for approximately 56 per cent of the Indian economy;

- The manufacturing and industries sector would contribute about 29 per cent; and

- Agriculture about 15 per cent.

Between 2005 and 2008, both, the services and the industries sectors grew at approximately 14-15 per cent on a nominal basis and 9-11 per cent in real terms.

Aggarwal said these sectors are likely to grow between 15-16 per cent in the next six years.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

Three groups of industry verticals, says Aggarwal, which together dictate the Indian stock markets, will be responsible for this growth.

Group 1: Retail, travel and hospitality (e.g., airlines, hotels, theme parks), financial services, healthcare (including medical tourism, alternative medicinal centers and spas, hospitals, pharmacies, and laboratories), entertainment (including the Indian movie and TV industries), and private education.

This group is expected to grow at an annual rate of 21-22 per cent per year, says Aggarwal.

Group 2: Hi-tech services and products like information technology and application development, business process outsourcing, knowledge process outsourcing, drug research and clinical research outsourcing, engineering services outsourcing, software and solutions related to the consumer Internet, software as a service, open source, software-cumservices, and telecommunications (both wireless and wire-line).

This group is expected to grow at an annual rate of 17-18 per cent annually.

Group 3: Automobiles, automotive components, electrical and electronic components, specialty chemicals, pharmaceuticals, gems and jewelry, textiles, and sectors related to construction, real estate, and infrastructure.

This group is also expected to grow at an annual rate of 17-18 per cent per year.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

Aggarwal says since productivity in public sector undertakings and family-owned businesses has improved at a very fast pace, these two sectors have become particularly important for the investing community.

An additional 80 per cent productivity improvement, says Aggarwal, would occur during 2005-15 on an average for a typical firm listed in the Indian stock markets.

However, he warns that India must address some fundamental issues like lack of investment in infrastructure to maintain its economic growth trajectory.

Fifty-six per cent of India's GDP is generated in the services sector, but lack of reliable power, transportation, and the logistics related infrastructure will begin to hamper its GDP growth rate, feels Aggarwal.

During FY 2006-08, the Indian government spent approximately 4.5 per cent of GDP on improving infrastructure and in FY 2009-10 it is likely to touch 5 per cent. However, it is far short of the 8-9 per cent of its GDP that China was spending after 18-19 years of liberalising its economy.

Fortunately, the Indian government is planning to spend 9 per cent of the country's GDP in infrastructure during 2010-15.

Indeed, if the government keeps its promise, then this investment would approximately equal $990 billion (assuming Rs = 1 USD), says Aggarwal.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

Expected inflation during the next six years

The build-up of inflationary pressure in the past one year has primarily been a result of a rise in food prices.

The relentless increase in food prices underscores low investment in agricultural infrastructure, supply chain, food processing and related technology, and irrigation; all of these are imperative so that the supply increases more rapidly than the demand, says Aggarwal.

Of course, double-digit inflation in India will send the entire economy into a tailspin because most people in India still live on approximately $3 per day and would simply not be able to buy food and other essential items, which in turn can destabilise the on-going economic reforms, he says.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

P/E ratios in India during 1995 and 2005

As of December 31, 2009, there were 23 government-recognised stock exchanges in India and there were more than 9,700 companies listed on these exchanges. The Bombay Stock Exchange lists about half of these companies (4,929).

As of December 31, 2009, the market capitalisation of the companies listed on this exchange was about $1.400 trillion (approximately 1.1 times India's annual GDP).

Ignoring dividends, both Sensex and BSE-100 have grown by 12.5 per cent annually in dollar terms between April 1, 1991 and March 31, 2005.

In contrast, NYSE 100 and Dow Jones grew at annual rates of 9.6 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively. Again, ignoring dividends, both Sensex and BSE-100 have grown by 13.4 per cent annually in Indian rupee terms during April 1, 1991 and March 2005.

On March 31, 2005, Sensex was valued at 6,492.82 (with a price earnings ratio of 16.05) and BSE-100 was valued at 3,481.86 with a price/earnings ratio of 13.72. This growth rate can be partitioned into the following three components:

- The companies comprising Sensex and BSE-100 have individually grown at an average annual rate of 9 per cent or more (in real terms) and 15 per cent (in nominal terms).

- The price-earnings ratio for companies listed in Sensex went down from 19.68 in March 1991 to 16.05 in March 2005, i.e., an average drop of approximately 1.5 per cent per year. Similarly, the price earnings ratio for companies listed in BSE-100 dropped by approximately 2.4 per cent per year.

- The difference between (1) and (2) approximates the average annual growth rate of Sensex and BSE-100 (of 13.4 per cent) as mentioned above.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

Of course, the future rise and fall of the stock markets is almost impossible to predict especially because even seasoned investors trade as much using their emotions (and the 'momentum' in the market) as the underlying fundamentals.

Aggarwal admits that his analysis does not take into account the following scenarios, although the likelihood of at least one of them occurring is quite high:

Potential of a double-dip recession or stagflation during 2010-12 in some developed nations: Both recession and stagflation in these economies are likely to have a ripple effect in India with a substantial out-flow of FII money, an overall negative sentiment with respect to price/earnings ratios in the Indian stock markets, and an inability of Indian firms to export their goods and services to these developed economies.

FII money flooding the Indian stock market: The inflow of FII money during April-December 2009 was because:

- FIIs consider India, China, and other emerging markets as regions of significant growth and where wealth would be created during the next decade;

- The interest rates that central banks are charging in many developed economies (e.g., the United States) is close to zero and therefore it is cheaper for FIIs to borrow money in their home-countries and then invest in emerging countries like India; and

- The stock markets in the US and other developed countries may have already peaked at least for now.

If these reasons continue to hold for the next six to twelve months and especially if the stock markets in developed economies continue to move sideways or downwards, FII money can flood the Indian stock market again, whose inability to absorb so much money will make it extremely volatile.

The fundamental trouble with this 'hot money' is that it can cause massive imbalances, says Aggarwal.

Click on NEXT to read more...

Sensex may touch 50,000 by 2015-end!

In spite of a substantial inflow of FII money and high remittances by Non-Resident Indians, India already has a current account deficit that is approximately $24 billion per year.

If the Indian rupee appreciates significantly -- for example, as it appreciated in 2007 to Rs 39 to 1 US dollar -- then this current account deficit will become much worse, especially because the import bill for crude oil will rise significantly.

Furthermore, since the Chinese currency is pegged to the US dollar and artificially kept lower by 15 per cent to 20 per cent of its 'real value', India will be unable to compete with China with respect to exporting products and services.

This, in turn, will substantially impede the growth of the Indian economy.

Another risk that may eventually hold back India's growth is the persistence of structurally high fiscal deficits. Fiscal stimulus, which was critical for sustaining economic growth given the global crisis, has further worsened the deficit picture.