| « Back to article | Print this article |

NDTV case forces channels to tackle rating issue

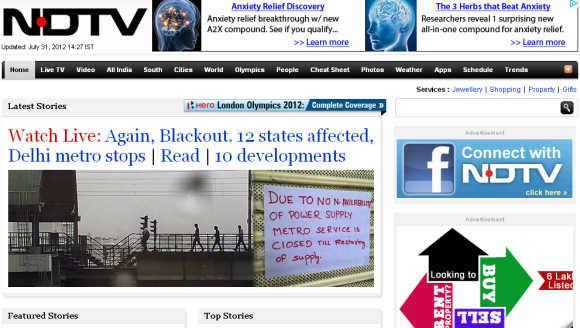

Last month, NDTV filed a suit in New York against Nielsen Holdings for over $1.3 billion in damages. Its contention: Nielsen's small sample size for TV audience measurement in India, combined with alleged corruption in its Indian arm, TAM Media Research, caused a loss of revenues for NDTV.

The lawsuit finally forces the Indian television industry to face a problem it has ignored, even exploited, for several years. How it deals with this will decide whether the 20 year-old, Rs 33,000-crore (Rs 330 billion) private television industry that reaches 148 million homes has grown up or will continue to behave like an adolescent going through hormonal deviations.

A TVR, or television rating, is a time-weighted average of the total time that people in sample homes spend watching a certain show. It is the currency used by advertisers to decide where to spend the Rs 11,600 crore (Rs 116 billion) they did in 2011.

TAM, a joint venture between AC Nielsen Research Services and WPP-owned Kantar Market Research, was appointed by a Joint Industry Body to provide this currency. The body is made up of broadcasters, media buyers and advertisers.

Click NEXT to read more...

NDTV case forces channels to tackle rating issue

As long as there wasn't much competition nobody bothered much with the currency. But after 2005, hyper-competition, especially in niche areas such as news broadcasting kicked in. From about 39 in 2005, there are currently 133 news channels in India.

As a result, the pressure for audience share and, therefore, ad revenues, stagnant at Rs 2,000 crore (Rs 20 billion), intensified. It did not take long for business heads to point to programming for low ratings and, therefore, poor financial performance.

This, in turn, put pressure on editors. Soon a currency that was meant for advertisers started being used by news editors, who began splitting hairs over why their show was two per cent less than a rival's at 9pm on a weekend. This makes no sense. Anyone who has been around the TV industry in India will tell you that cherry-picking data is an industry joke of sorts.

Any channel or show can be the number one, depending on how it cherry-picks data. So, channel X could be the number one news channel - in the age group of 60-plus between 3 and 4pm, on Wednesdays.

Click NEXT to read more...

NDTV case forces channels to tackle rating issue

TAM's defence? Because the sample size is small (8,150 homes covering 36,000 people), cutting it too fine makes it unstable, throwing up all sorts of weird skews. So, one part is broadcasters over-interpreting the data from a sample size that is too small for their genres. (Note that entertainment broadcasters, blessed with a larger sample, don't seem to be complaining as hard.)

Couldn't TAM have a larger sample size? Its answer - the economics don't justify it. According to estimates Nielsen's TV audience measurement business in India is about Rs 50 crore (Rs 500 million) and brings in a net profit of around eight per cent.

Half of this goes to Kantar. If the sample size has to go to a healthy 30,000 homes (or 15,000 people), as suggested by the Amit Mitra Committee report (2010), it would cost Rs 660 crore (Rs 6.6 billion). Who will foot this bill?

Even so two questions remains. Are ratings fixable? Yes they are, up to a point. You could catch some member of the field staff, pay him to reveal the meter home, and fiddle. But much of this should show up when the data gets validated.

Click NEXT to read more...

NDTV case forces channels to tackle rating issue

Did NDTV's competitors fix ratings? That is something only a judge in New York will decide once the lawsuit is admitted. For now Nielsen, it seems, has decided to fight it out in court.

Meanwhile, a crisis of sorts looms for the broadcast industry. If there is no currency how can the TV economy function? What are the solutions?

One, is BARC, or Broadcast Audience Research Council, an idea floated six years ago. BARC was formed by the Indian Broadcasting Foundation, Indian Society of Advertisers and Advertising Agencies Association of India. The Mitra committee suggested registering it as a not-for-profit company with a cess on the industry to fund it.

BARC, formed earlier this year, has already missed its deadline to begin operations. Given the ruckus on ratings it is strange that broadcasters - and, more importantly, advertisers - have been so slothful in moving on an alternative. It seems to suggest that everyone is happy with their inadequate currency.

Two, advertisers and broadcasters should stop buying Nielsen's ratings data, dis-empanel it and invite other companies to pitch their tent in India. Nobody, however, seems to have given up on TAM yet.

Three, if they continue to use TAM data, then using it so that sample errors are ironed out might work better.

For niche genres - such as news or infotainment - it makes sense to look at monthly trends instead of hourly or minute-by-minute data. This is what the industry did in the US, the UK and Australia after similar issues cropped up.

It is a pity that a court in New York will rule on the currency used by the Indian TV industry. It really shouldn't have gone that far.