| « Back to article | Print this article |

How villagers built a tourist resort

Located in a remote landscape of dry and unending flatness, it was built in 2005 through a partnership between the village community and a Bhuj-based NGO called Hunnarshala Foundation.

The project as a whole was the result of a partnership between the village of Hodka, the district collectorate, United Nations Development Program (UNDP), Kutch Mahila Vikas Sanghatan and Hunnarshala Foundation.

Shelter and enclosure

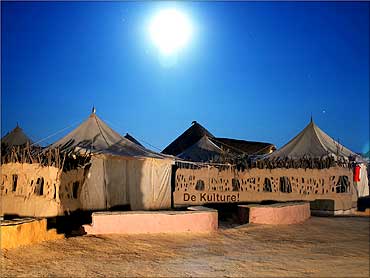

The drive from Bhuj to Hodka opens up the subtle drama of a flat, scrub-covered landscape. When you arrive at the resort, you begin to imagine how an oasis might feel to a desert traveller.

The even mud finish wraps over the rising contours of open spaces, and envelops the cluster of traditional bhungas (circular, thatch-covered mud huts) in the background. The traditional painted decoration on the mud surfaces brings delicacy into the spare, sculptural feel of this composition. Click NEXT to read on further. . .

How villagers built a tourist resort

The resort is small (three bhungas, two family tents and seven double-bed tents adding up to only 2,000 sq ft of built up area), but it offers the luxury of neatly designed open spaces finished in a layer of fine mud.

The bhungas and tents are broadly arranged around the central open space which also has a platform for traditional performances near the tented dining facility. One evening performance by traditional musicians that I attended was made all the more memorable by the pitch darkness in the landscape around, an almost impossible environment in our towns and cities.

The scrub forest around comes right up to the resort and only the raised plinth of the open space and a white border painted in lime on the raised edge marked the end of the campus and the beginning of wilderness.

How villagers built a tourist resort

Small thoughtful details like these complement the efficient overall logic of the resort plan, to make the experience memorable. It may surprise those who think that only professionals can design, but the villagers were equal partners in the design and the construction of the resort.

Says Sandeep Virmani, managing director of Hunnarshala and an architect by training, "All design decisions were made with the villagers at the centre of the process. They also built the resort themselves using traditional methods. As architects and engineers we mainly helped rationalise some decisions and also to design the plumbing and other services".

Some of the craftspeople have also landed work in bigger cities and towns. Ramaben, the woman who designed and led the execution of all the painted decoration and murals, has successfully completed a commission in Rajkot after the success of the resort.

How villagers built a tourist resort

More important than involvement in construction is the fact that the resort is a project owned by the community itself. Rarely do host communities directly initiate tourism enterprises or control them once they begin.

Sham-e-Sarhad is a rare example of a community-run tourism project, and was part of a nation-wide endogenous tourism project which had the support of the local administration, the UNDP and local NGOs.

Usually, local communities benefit from tourism the least, with almost every kind of profit being made by middlemen who are often outsiders. The irony is that tourists also get a bad deal, whether they know it or not. They visit a place to experience the local culture, meet people and enjoy the landscape.

How villagers built a tourist resort

Tourism-as-usual degrades all three easily. What might have been an experience easily becomes an act of consumption, since the experience is organised around the exchange of money.

Thus, the tourist is unable to develop a human relationship with the place, people, landscape and culture of the host community. Host communities and their environments thus easily get "used" and discarded.

By contrast, a project like Sham-e-Sarhad approaches tourism differently. The fact that the host community itself sets the agenda is crucial. It helps ensure that the community's self-interest would constrain the way tourism alters or appropriates the landscape, people and culture.

Since tourism is also seen as one among many development options, it is unlikely to be allowed to overshadow the concerns of other activities for survival and development.

How villagers built a tourist resort

Sham-e-Sarhad also indicates how community-run tourism projects can be a win-win situation for everybody. Visitors at Sham-e-Sarhad are thought of as guests interacting with "owners" of the resort (who also serve them) and custodians of the local environment.

Thus, visitors can, if they wish, actually engage with the people, food, music, and the unusual landscape around in a more meaningful relationship. This includes the possibility of tours and interaction with the traditional craftspersons of the village in their own homes.

Earth works

Mud buildings can last for hundreds of years as they do in many parts of India. Apart from getting the mix right, it is important to give the mud building a good roof and plinth (usually stone or brick).

As is well known, if water gets into a mud wall it soon destroys it. There are many ways of building in mud, and all have been used in this resort. In most methods mud is "stabilised" with some additives ranging from cow dung and lime to cement:

Rammed earth: Mud is placed or poured into a wooden formwork to cast the walls.

Wattle and Daub: A framework of wooden members and reeds is erected and wet mud is plastered over it. Sometimes gaps are deliberately left to create perforated screens.

FACT FILE

LOCATION: 65 km north of Bhuj, at the edge of the Rann of Kutch near the border with Pakistan.

HOW TO GET THERE: Hodka is 65 km by road from Bhuj. Bhuj has a rail link and an airport (latter connected only to Mumbai). From Ahmedabad, it's 400 kms by road.

SEASON AND OCCUPANCY: Open only from October to March. It can house 28 people at a time in 3 bhungas,& 2 family tents and 7 double occupancy tents(plans for expansion are in progress) and host 50 diners.

TARIFFS (BEFORE TAX): Rs 1,800 for single occupancy of tents to Rs 3,200 for double occupancy of Bhungas.