| « Back to article | Print this article |

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

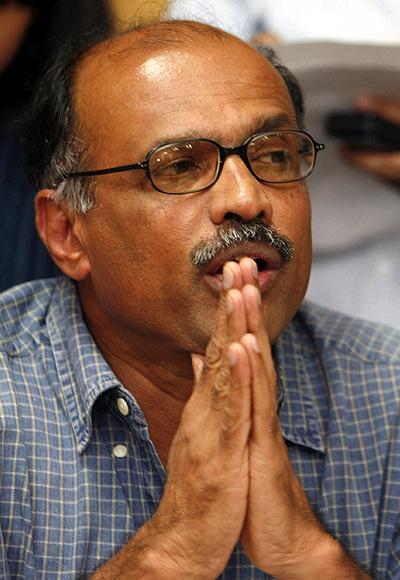

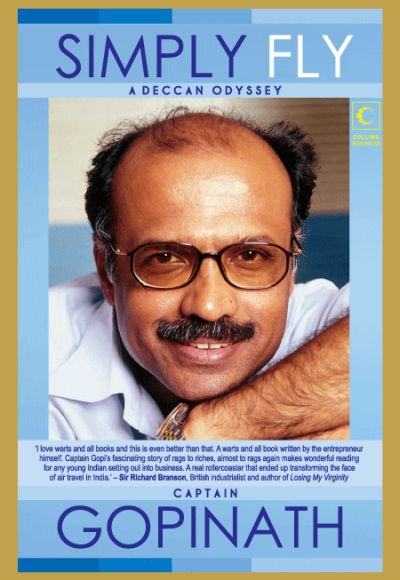

When G R Gopinath launched his maiden low-cost carrier flight from Bengaluru to Hubli in August 2003, he couldn’t know this would change India’s aviation history.

Gopinath’s Air Deccan was changing the rules of the game -- it audaciously offered fares on a par with or lower than travelling in a II class air-conditioned rail coach and nearly half of that on travelling in a I AC berth.

And, about a third of what full service air carriers were charging their well-heeled customers.

Gopinath said he’d offer no food or frills or even seating numbers.

But first-time flyers (half his passengers) lapped it up, as they’d never earlier dreamt they could fly, too.

Air Deccan also opened markets in smaller cities and towns, such as Jabalpur and Hubli, where hitherto no one flew, by connecting these with short-haul ATR aircraft.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

The model, in hindsight, seems a no-brainer in a country with so many cost-conscious travellers and airline travel frequency so abysmally low.

Together, LCCs have 10 years later grabbed 68 per cent of the passenger market, from a mere 1.3 per cent in 2004.

Most FSC’s are struggling financially, forced to drop fares to the same levels as LCCs, though their costs are far higher, to only keep afloat.

Viability

That is one part of the story about Gopinath as pioneer.

There is another about developing a faulty and unviable business model, not sustainable from the beginning.

After all, he was selling fares lower than his cost of operations, hoping the volumes would some day help him make profits on the low margins.

Critics say he seemed to forget LCCs have no control on 50-60 per cent of the cost (including aviation turbine fuel, lease rentals and the dollar).

No model could sustain forever on only price.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

When his monopoly in the LCC skies was challenged by newer players that did the same but also ran much more efficient airlines, he went under -- the biggest casualty of his own strategy.

He was forced to sell his airline to Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher Airlines, to see it being disbanded fairly soon.

Yet, his model was replicated by competitors that came into the market between 2005 and 2006.

They tweaked it, to improve customer services and operations so that there were fewer delays and cancellations, bringing in the reliability missing in LCC operations.

For that, they charged a slight premium.

“Travelling LCC did not mean you had to travel with discomfort and lack of reliability. That is what new LCCs learnt from Deccan’s mistakes,” says a competing LCC boss.

So, as with Air Deccan, new LCCs such as IndiGo and SpiceJet cut the turnaround time of planes from an hour of the FSC to less than 30 minutes.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

Routes were so made that each plane would fly at least 12 hours a day, against less than 10 hours on FSCs.

About half of the bookings were made online, reducing costs as agents didn’t have to be paid commissions.

And, they also did things Air Deccan did not focus on. IndiGo for instance gave full attention to reliability.

It was able to set new benchmarks on ensuring flights were on time and created records for the fewest cancellations.

It also ensured the fleet was young, the average age being not more than two and a half years, better in many ways than FSCs were offering.

So obsessed was it with timeliness that it started a campaign defining IST as IndiGo Standard Time.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

Possible because IndiGo made deft acquisition deals for new aircraft.

Even before it started the airline, it ordered 100 aircraft from Airbus and stuck to the delivery schedule.

The analysts say it ensured they got a substantial discount on the planes; it also helped them do long-term route planning carefully.

And, unlike Air Deccan, it preferred to have only one type of aircraft and avoided adding in costs that the former had because of having ATRs and Airbus planes, with different cost centres.

Even GoAir was careful, despite being the smallest in the segment, not to make the mistakes of Air Deccan and quickly expand across the country.

Instead, in 2008, it decided to become a strong player around a hub, rather than spread all over the country, and grow step by step.

That is why it had a little over 10 per cent share of the Mumbai market in 2008, though its all-India share was four per cent as it put in over nine flights a day.

GoAir has continued this strategy with its smaller fleet.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

Pricing conundrum

Yet, for LCCs, pricing at an affordable level without losing money has always been a tightrope walk.

At one level through the past decade, air fares have increased but much slowly than the increase in their costs. LCCs note ATF fuel price between 2005 and now has gone up three times, over half of operational cost.

The dollar in that period appreciated against the rupee nearly 41 per cent, making leasing of aircraft that much more expensive.

A senior LCC executive says in the past decade, net fares for LCCs on the Delhi-Mumbai route, for example, have gone from Rs 2,800 to Rs 3,700-4,000 currently, up 40 per cent. But costs have gone up nearly twofold.

There are also new imposts such as the service tax, User Development Fee and Airport Development Fee, which passengers have to fork out.

As with other businesses, LCCs also had to confront the sustained slowing in the economy from 2011.

Suddenly, there was over-capacity, as the anticipated increase in flyers did not materialise.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

They had no option to price wars for wooing customers, forcing many to sell fares at below cost or very low margins.

And, there was a new problem.

FSCs have, to woo back customers they have been losing to LCCs, been forced to drop their fares to match with LCCs.

This is although their costs are 40-50 per cent higher and even if it meant they’d be bleeding big time.

Through the decade, FSCs on the Delhi-Mumbai route have seen their fares go down from an average of Rs 6,500 to a mere Rs 4,500, down 30 per cent.

They’ve also pared costs drastically but it’s not enough to absorb the increased costs of fuel and the rupee’s depreciation.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

How to make an airline pay when flyers won't

Big brothers stagger

Yet, despite the challenges, the three LCCs together made a profit of Rs 700 crore or Rs 7 billion (with IndiGo and GoAir in the black and SpiceJet in the red) in 2012-13, against a staggering loss of Rs 5,678 crore (Rs 56.78 billion) by the two FSCs, Air India and Jet Airways.

Even when FSCs started a price war and dropped fares in the second quarter of 2012-13, without any reason, the LCCs weathered the storm much better than their bigger brothers.

While the latter made an estimated total loss of $120 million in the quarter ending October, FSCs lost $400 mn, according to a report of the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation, despite having begun the price war.

The next few months, airline companies say, would be tough.

Fares, raised 20 per cent in the third quarter, were not enough to absorb the increase in costs.

Yet, the message is pretty clear: LCCs, with their costs, are in a much better position to fight a war of nerves on price.

FSCs, with a much higher cost of operations, will have to admit defeat or go under.