Photographs: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters

The urbanisation of the world continues apace and is one bright spot in an otherwise challenging global economic environment.

The shift in economic balance toward the East and South is happening with unprecedented speed and scale. We are quite simply witnessing the biggest economic transformation the world has ever seen as the populations of cities in emerging markets expand and enjoy rising incomes - producing a game-changing new wave of consumers with considerable spending power.

Let's take a look at how the economic power is shifting from West to East, according to a recent report published by The McKinsey Global Institute.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

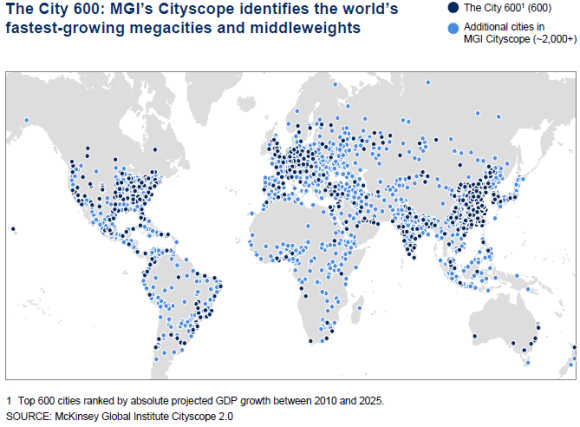

The MGI Cityscope is a database of more than 2,600 cities around the world that allows us to understand the evolving shape of global urban economies; extract many different city rankings and groupings by region, variable, and target market; test the growth momentum from doing business in particular geographies; and develop projections of growth in urban markets of a range of products and services.

For each city, the database includes data for 2010 and forecasts for 2025 on population by age group (children below the age of 15), working-age population (aged 15 to 64), and the older population (aged 65 and above), GDP and per capita GDP (at market and purchasing power parity, or PPP, exchange rates as well as at predicted real exchange rate, or RER), and number of households by income segment (in four income categories defined by annual household income in PPP terms: less than $7,500, $7,500 to $20,000, $20,000 to $70,000, and more than $70,000).

MGI has developed city-specific data from existing public survey data, MGI's citylevel datasets developed as part of our previous research, selected data from external providers, and MGI's country- and region-specific models of city growth to 2025.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

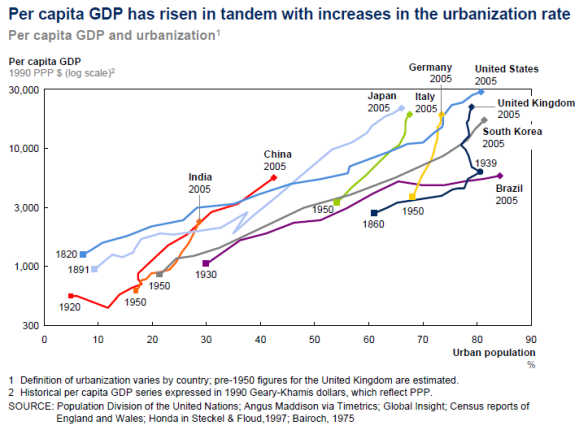

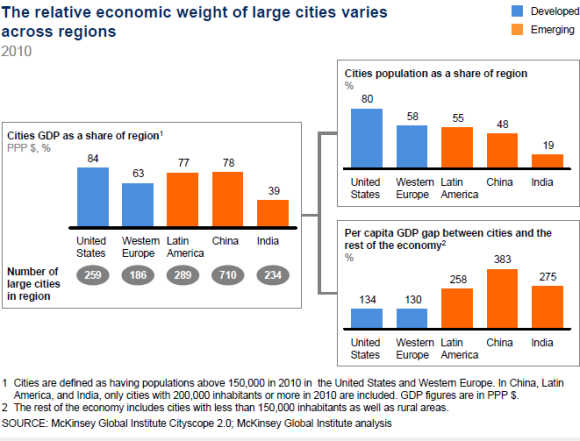

Until 1500, Asia was the centre of gravity of the world economy, accounting for roughly two-thirds of global GDP. But in the 18th and 19th centuries, urbanisation and industrialisation vaulted Europe and the United States to prominence.

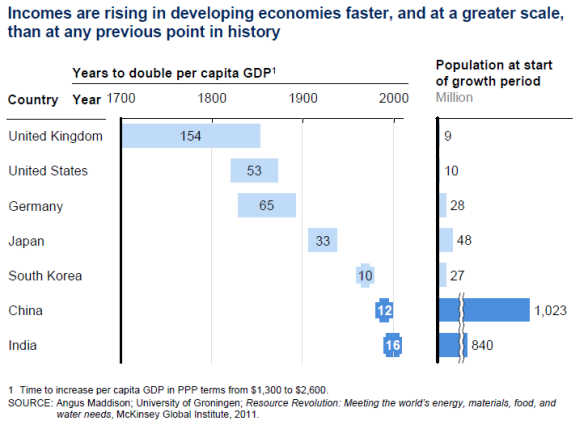

We are now observing a decisive shift in the balance back toward Asia - at a speed and on a scale never before witnessed.

China's economic transformation resulting from urbanisation and industrialisation is happening at 100 times the scale of the first country in the world to urbanise - the United Kingdom - and at 10 times the speed.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

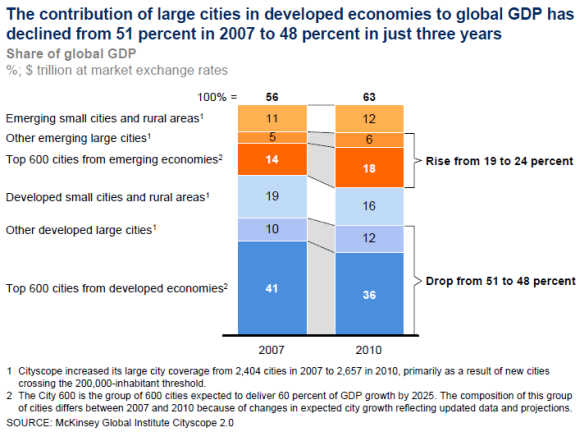

The recession that has hit the United States and Western Europe particularly hard has accelerated the shift in the global economic balance.

From 2007 to 2010, the GDP of large Chinese cities rose from 20 per cent of that of large cities in the United States to 37 per cent. In these three years alone, three more Chinese cities reached megacity status with populations of 10 million or more - one new megacity a year.

Contrast that with the developed world, whose urban landscape is far more mature. Between now and 2025, Chicago is the only city in the developed world expected to pass the 10 million population mark.

But the speed at which the global balance is changing is not simply a China and Asia story. In 2007, the GDP of Latin America's cities was 26 per cent that of their European counterparts; by 2010, that figure had risen to 37 per cent.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

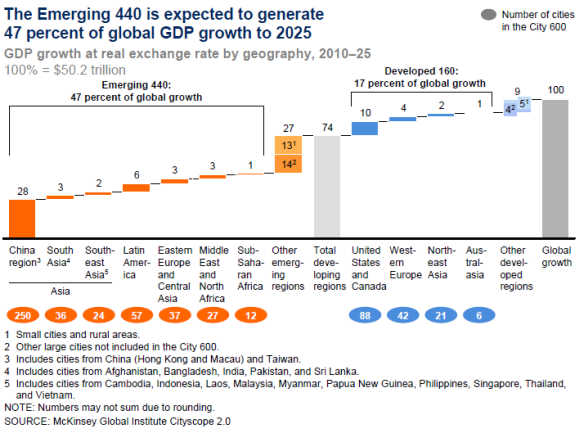

Urban growth is highly concentrated in just a few hundred cities and will continue to be. Our analysis suggests that just the top 600 cities by their contribution to global GDP growth to 2025 - a group we call the City 600 - will generate nearly 65 per cent of world economic growth in this period.

Today, the City 600 is home to just over 20 per cent of the world's population but accounts for nearly $34 trillion, or more than half, of global GDP.

Between 2010 and 2025, we expect the City 600's combined GDP to nearly double to $65 trillion. But the most dramatic chapter of today's urbanisation story is the role played by the so-called Emerging 440.

These emerging market cities in the City 600 will account for close to half (47 per cent) of expected global GDP growth between 2010 and 2025.

The Emerging 440 boasts 20 megacities, including Shanghai in China, Sao Paulo in Brazil, Istanbul in Turkey, and Lagos in Nigeria.

Together these megacities will generate an estimated $5.8 trillion of GDP growth by 2025, a compound annual growth of 7.6 per cent - almost double the growth rate expected for the global economy as a whole.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

But more than 400 cities of the group are middleweight cities with populations of between 200,000 and 10 million, spread out across 57 countries and every continent except for Oceania.

We expect these middleweights to grow even faster at an eight per cent annual compound rate, contributing $17.7 trillion in GDP growth by 2025.

In the Emerging 440, China is an important part of the equation with 242 cities in this group, of which 236 are middleweights.

Latin America has 57 cities in this dynamic group, 53 of them middleweights including Belo Horizonte in Brazil and Cali in Colombia.

South Asia, including India, has 36 cities in this group. There are 28 Indian middleweight cities in the Emerging 440, including Bangalore, Pune, and Kochi.

Africa and the Middle East together contribute 39 cities to the group, and 37 of them are middleweights, including Angola's capital Luanda, Kumasi in Ghana, Port Harcourt in Nigeria, and Doha in Qatar.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

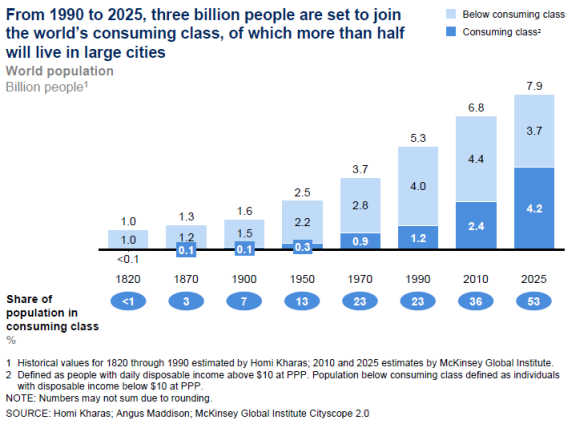

The increasing size and power of cities in emerging markets have tangible and dramatic economic benefits that translate into rising incomes.

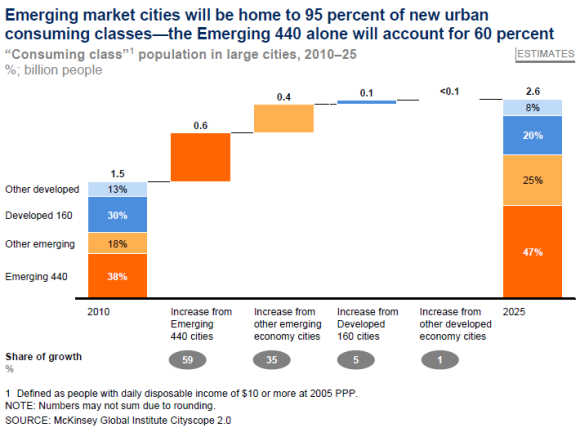

We expect to see one billion more people in cities worldwide become members of the consuming classes, with enough income to buy the very basic necessities and to have some discretionary income to spend on consumer goods and services.

That's a rise of 70 per cent from today. These growing consumer classes will drive rapid growth in demand for many goods and services.

Across all large cities, we expect annual household consumption to rise by more than $20 trillion to 2025 - of which about $14 trillion will be in large cities in emerging markets.

In the Emerging 440 alone, we see consumption increasing by more than $10 trillion.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

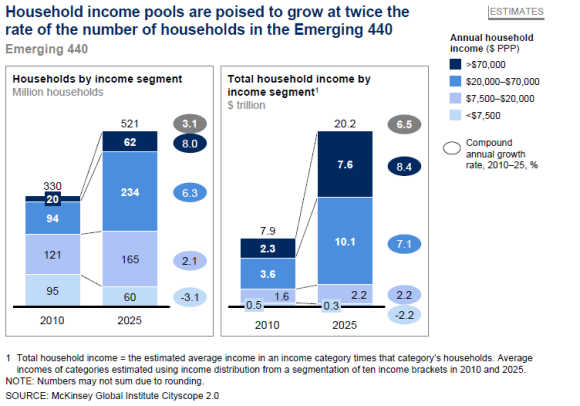

The growth in demand for many consumer goods will exceed the expansion of the consuming classes for two main reasons.

First, household incomes are rising faster than the number of households and individuals in consuming classes.

Second, and more important, higher shares of the populations of many large emerging economies, including China and India, are moving into income segments where the consumption of many goods and services takes off rapidly.

In China, for instance, spending on dining out starts to take off at annual incomes of around $3,000 per household and, by about $9,000, is on a firm and steep upward trajectory.

Spending on transport and communications starts increasing strongly as incomes reach around $6,000 per annum.

The recent growth in Chinese consumer markets reflects these inflection points. Between 2004 and 2011, per capita sales of electronics and video appliances rose fourfold and clothing and shoes rose fivefold in real terms, outpacing a 3.4 times increase in per capita income during that period.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

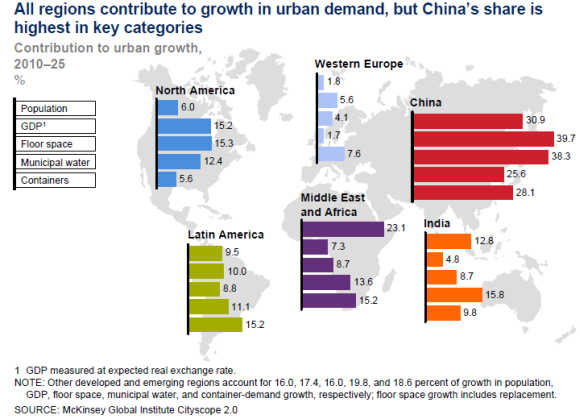

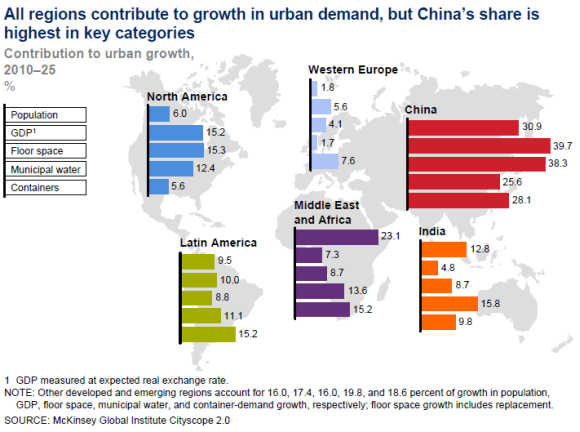

The world's new urban consumers will have an impact far beyond sales of goods and services. To cater to their needs, cities will need to invest heavily in infrastructure.

We estimate that cities will need annual physical capital investment to more than double from nearly $10 trillion today to more than $20 trillion by 2025.

Urban centres in emerging economies will make most of this investment. MGI has looked at three sectors in particular detail - buildings, port container capacity, and municipal water distribution.

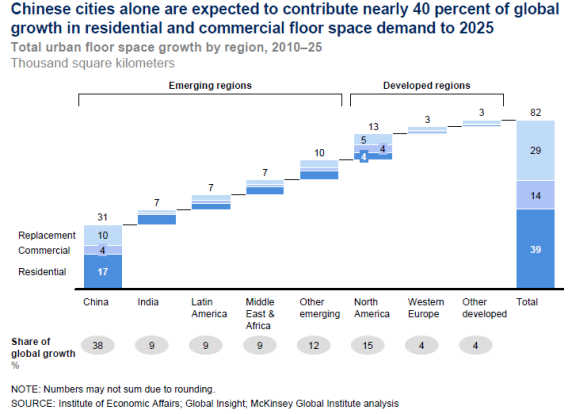

Buildings: By 2025, cities will need to construct floor space equivalent to 85 per cent of all of today's urban residential and commercial building stock.

In the Emerging 440 alone, we see demand for residential and commercial floor space growing by 44,000 square kilometres.

The urban building boom will require cumulative investment, including for replacement buildings, of nearly $80 trillion.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

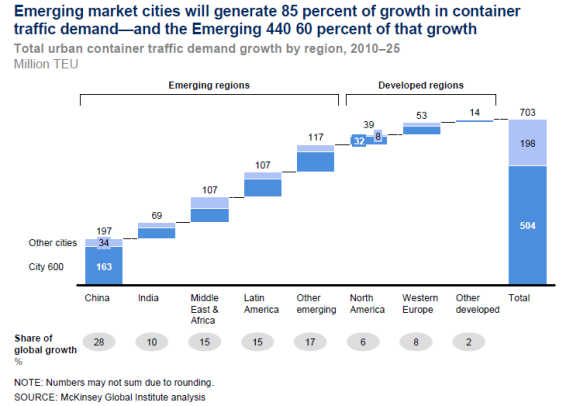

Container capacity of ports: The capacity of ports to handle global container traffic needs to rise by more than 2.5 times from today's level to meet rising consumer demand for products across the globe.

The investment needed to expand port capacity to 2025 exceeds $200 billion by our reckoning, with 85 per cent of it taking place in emerging markets.

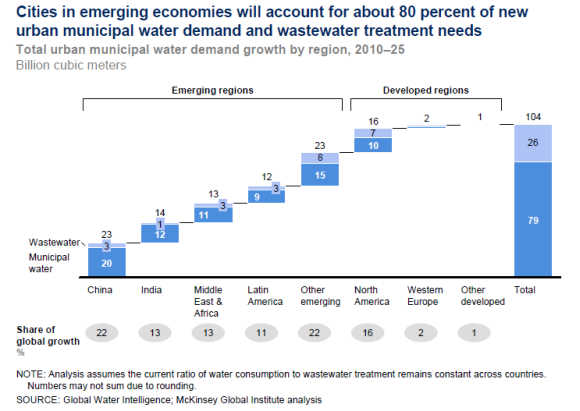

Municipal water: We expect urban municipal water demand to rise by almost 80 billion cubic metres, equivalent to more than 20 times the water consumption of New York today and 40 per cent above today's urban global level.

Serving rising demand will require cumulative investment in water supply and wastewater treatment of about $480 billion by 2025, of which about $200 billion will be in the Emerging 440.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

Surging urban consumer demand, and the investment necessary to meet it, is on course to inject more than $30 trillion of additional annual spending into the world economy by 2025.

This is undoubtedly a welcome source of growth. But consumption and capacity building in the developing urban world are already straining the global supply of capital and natural resources.

The urban world has already contributed to a jump in the global investment rate from 20.8 per cent of GDP in 2002 to 23.7 per cent in 2008, followed by a dip during the global recession of 2009.

Increases in the prices of energy, land, food, and water in the first decade of the 2000s have wiped out the decline in prices observed during the entire 20th century.

The new consumers we see to 2025 will only increase the stress on demand and prices, potentially for a prolonged period.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

So national, regional, and local governments, as well as businesses, need to manage the consumption and investment boom.

Cities have the potential to handle the stresses well. Densely populated urban centers can use resources more productively than dispersed cities and rural areas.

Nevertheless, most growing cities can do better in this regard. Cities that under-invest in infrastructure and fail to keep pace with their expanding populations and their demands - or indeed invest inefficiently or in the wrong things - can find themselves hitting barriers to growth.

Conversely, if cities manage their capacity building well, there is a large opportunity not only for the world's investors but also to build more productive capacity that is less costly and more efficient in environmental terms for decades to come.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

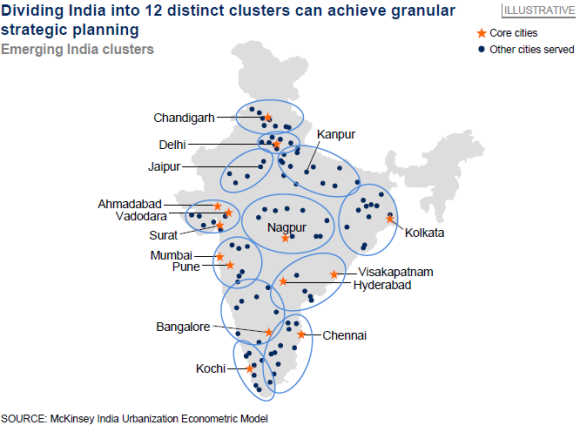

To capture the significant opportunity that urbanisation offers them, companies need to take a scientific approach to locating the most promising markets for their businesses.

Urban markets will be highly diverse, and many of the fastestgrowing segments are likely to be in middleweight cities in emerging economies that are simply not on the radar screens of many companies.

As illustration, many companies might be hard-pressed to identify the geographic location of Surat, Foshan, and Porto Alegre, let alone even the broad characteristics of their economies.

Yet all three have populations of more than four million. Surat is in western India and accounts for about two-fifths of India's textile production; Foshan is China's seventh-largest city by GDP; and Porto Alegre is the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, the fourth-largest state in Brazil.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

Companies that understand the shifting urban marketplaces relevant to their businesses and build an early presence with sufficient scale are likely to benefit from being the incumbent with better market access and higher margins.

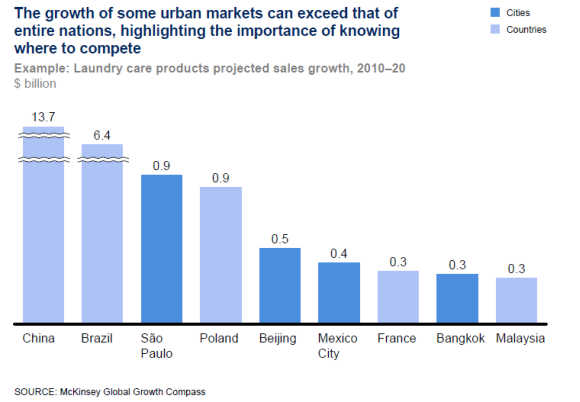

Looking at cities rather than countries as a whole can be eye-opening. Take laundry care products as an example. We expect to see more sales growth of these products in Sao Paulo than in either France or Malaysia over the next decade.

Yet, disappointingly, most companies are still not looking at cities as they calibrate strategy.

A new McKinsey survey finds that less than one in five executives is making location and resource decisions at the city, rather than the country, level - and respondents did not expect this low share to increase over the next five years.

Of those surveyed, 61 per cent say that their executives do not plan at the city level because cities are perceived as "an irrelevant unit of strategic planning".

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

Rapidly growing cities in the developing world face a complex and challenging managerial task in keeping pace with their expanding populations and their rising expectations.

To avoid constraints on their growth, cities need to be able to plan the urban environment for sufficient housing and effective transportation, ensure that sufficient finance is available to support both operational and capital spending of electricity, telecommunications, water, and other services, and, through smart regulation, provide an environment that encourages entrepreneurialism and business investment.

Cities that fail to meet the aspirations of the millions who are migrating in search of better opportunities run the risk of congestion, pollution, and insufficient public services becoming barriers to growth.

Growth has already slowed down in many megacities around the globe because they have not kept pace with the needs of their expanding populations.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

Most developed regions have already reaped the majority of economic benefits from urbanisation, and city leaders are more likely to be grappling with growth that is too slow rather than growth that is so rapid as to make its management

difficult.

In the near term, many cities are struggling to overcome deleveraging and persistent unemployment. In the longer term, slower population growth, ageing, and increasing global competition are creating headwinds against growth.

As we have observed in the past, some cities will outperform their peers while others will decline. How individual cities will fare depends on how well they are positioned to take advantage of - or mitigate the negative impact of - the relentless trends shaping their economic environment.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

The first step for cities in developed regions is to understand their current strengths and weaknesses, as well as the impact of demographic and other trends on their prospects.

Chicago, for example, has launched a major effort to compile a fact-based profile of the city's strengths and weaknesses as the basis for a new growth strategy.

Cities then need to translate the audit into tangible initiatives that matter to citizens and businesses. As the balance of global economic power shifts to emerging cities, those urban centers that have good connections - or build them - with the fastest-growing cities in the developing world will be in a better position to take advantage of the opportunity they offer.

Cities can also find ways to limit the impact of unfavourable trends.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

The way policies and strategic plans are carried out is a critical success factor for national, regional, and local economic development plans, particularly given today's weakening public finances.

To sustain and improve their services, most cities will need to be able to do better with less. Involving the private sector can help bring in expertise as well as intelligence about what constraints may be limiting their growth in a particular city and how to overcome them.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

In the past three years alone, a period in which recession constrained growth in the cities of developed economies even while urbanisation proceeded at a furious pace in the emerging world, there has been a decisive shift to the East and South.

Between 2007 and 2010, the GDP of large cities in emerging markets increased from 37 per cent of their counterparts in developed economies to 50 per cent.

During the same period, in the East, the combined GDP of China's large cities increased from 20 per cent of that of large cities in the United States to 37 per cent.

Three more Chinese cities vaulted into the megacity bracket with populations of 10 million or more - that's one new megacity a year.

Contrast this with the much slower pace of the mature urban shift in the developed world. In the period to 2025, developed regions are expected to create only one new megacity - Chicago in the United States.

In the South, the GDP of Latin America's cities has risen from 26 per cent of that of their European counterparts to 37 per cent in these three years measured at market exchange rates.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

Urban growth is already, and will continue to be, highly concentrated in just a few hundred cities. Today, the City 600 - the top 600 dynamic metropolises by contribution to global GDP growth - are home to just over 20 per cent of the world's population but account for $34 trillion, or more than half, of global GDP.

Between 2010 and 2025, we expect the City 600's combined GDP to increase by more than $30 trillion and thereby contribute nearly 65 per cent of global GDP growth.

The world's very largest megacities are no longer the major drivers of global growth. We estimate that today's 27 megacities will contribute about 15 per cent of global growth to 2025, proportional to their economic weight today - and that two-thirds of worldwide growth will come from middleweight cities.

...

How the world's economic centre is changing

The most dramatic story of today and the next few years is the shift in economic clout from cities in the developed world to those of emerging markets.

Only just over 440 cities in developing countries - the Emerging 440 - will generate an estimated 47 per cent of global growth between 2010 and 2025.

Only 20 of the Emerging 440 are megacities, the rest being middleweights. A little over half of the Emerging 440 - 242 in total - are in mainland China, and these cities alone will contribute more than one-quarter of the total growth.

But there are rising urban centers in all emerging regions. There are 57 Latin American cities in this dynamic group, 30 of them in Brazil and 10 in Mexico.

We expect these cities to contribute six per cent of global GDP growth, roughly the same share expected from City 600 cities in Western Europe, Japan, and South Korea combined. Africa and the Middle East together have 39 cities in the Emerging 440, and Eastern Europe and Central Asia 37.

article