| « Back to article | Print this article |

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

Walmart's entry into India will mean profits for the Americans and jobs for the Chinese, says Mohan Guruswamy.

Foreign investment is invariably beneficial as it creates jobs, adds value, and contributes to the GDP.

Companies like Hyundai, Ford and Honda have built a giant automobile industry in India now producing over 2 million cars and tens of thousands of new jobs.

By 2017 India will emerge as the third-largest car-making country in the world, producing over 7 million automobiles. This would not be possible without foreign investment, technology and leadership.

In sector after sector, foreign investment has created huge new capacities catering to domestic and foreign markets. The level of foreign ownership makes no difference to the contribution foreign companies make to the economy.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

The desirability of foreign investment must never be questioned as long as it creates jobs, adds value and contributes to development.

And these are just the factors that go against foreign direct investment in retail.

Study after study in developed and developing countries alike have shown that big box retail rather than creating jobs, destroy jobs.

In fact their utility in developed economies is due to the labour savings they achieve. This, combined with bulk buying and the recourse to monopsonic (the opposite of monopoly) practices, results in pushing down producer prices, undoubtedly with resultant benefits to the consumer.

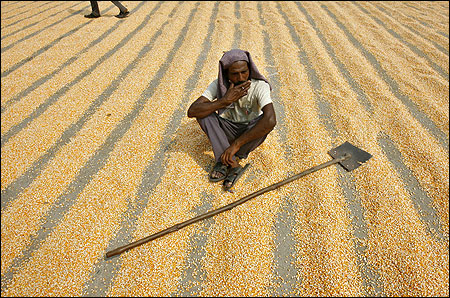

On the other hand, the more of a commodity large retailers purchase in bulk, the lower the prices growers of agricultural commodities obtain! Studies by FAO and Oxfam attest to this.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

For instance, a decade ago coffee growers earned $10 billion from a global market of over $30 billion but now they receive less than $6 billion out of a global market $60 billion.

The cocoa farmers of Ghana now receive only 3.9 per cent of the price of a typical milk chocolate bar but the retail margin hovers around 34.1 per cent.

A banana farmer in South America gets 5 per cent of the retail price of the banana while 34 per cent accrues to distribution and retail.

The average size of a Walmart is about 100,000 sq ft and the average turnover of a store is about $53.2 million, each employing about 300 workers. The turnover per employee averages $175,000.

Walmart has a 9 per cent return on assets, a 21 per cent return on equity, and its CEO Michael Duke's $35 million salary, when converted to an hourly wage, worked out to $16,826.92. In comparison to this new employees are paid $8.75 an hour that would gross $13,650 a year.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

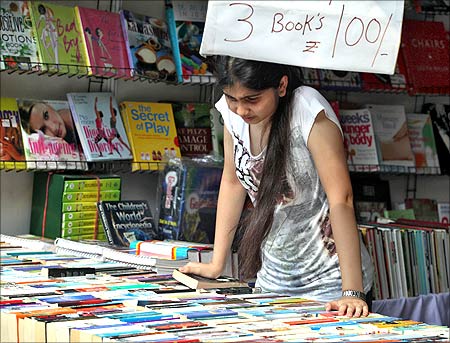

By contrast the average Indian retailer had an annual turnover of Rs 330,000. Only 4 per cent of the 12 million retail outlets were larger than 500 sq ft in size.

India has 53 towns each with a population over 1 million. If Walmart were to open an average Walmart store in each of these cities and they reached the average Walmart performance per store -- we are looking at a total turnover of over Rs 141,000 million with the employment merely of about 16,000 persons. Extrapolating this with the average trend in India, it would mean displacing about 758,000 persons.

Quite clearly Walmart is not going to create more jobs in India. On the contrary it will cause a massive loss of jobs in direct retail.

This is the experience in the USA also. A 2004 study by the Pennsylvania State University concluded that counties with Walmart stores suffered increased poverty, and suggested that it caused displacement of higher paid workers in small family-owned retailers.

Another 2007 study has shown that towns in Nebraska with and without Walmart fared similarly different in terms of joblessness and poverty.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

A study of Walmart's expansion in Iowa found that 84 per cent of all sales at the new Walmart stores came at the expense of existing businesses within the same county.

The major argument in favour of the benefits a Walmart or Carrefour will bring centers on the perceived benefits to agriculture and better prices to the farmer.

Empirical evidence from many countries, where big retail chains dominated, show that on the contrary farm realisations actually decline.

A recent joint study in Finland by Agrifood Research Finland and Pellervo Economic Research Institute reveals that for each kilo of rye bread purchased in 2010, for which the consumer paid 3.52 Euros, 1.24 went to the seller, while the grower received only 14 cents.

A further 1.74 Euros were shared by the milling company and logistics, while the rest went to the state as taxes. The study also revealed that while the trade got 19 per cent of the takings on food, it went up to 29 per cent in 2009.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

Finally, the study showed that food prices rose faster than other consumer goods between 2000 and 2010.

Big business and MNC's like PepsiCo, Cargill, ConAgra and even ITC have been procuring food grains and farm produce for several years now and there is no evidence that general prices have increased.

Even where better prices were paid to contract farmers, data available suggests that input costs have been higher.

Simple economic logic tells us that nobody pays more for a commodity that can be obtained for less. Business is about extracting profits and not about charity.

Protagonists of FDI in retail talk a lot about modernising the supply chain. Consider this: The National Sample Survey relating to household expenditures reveals that fruits and vegetables only account for 9.88 per cent of urban household expenditure.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

It is widely agreed that the supply chain that links the Indian producer to the domestic consumer is primitive, outmoded and wasteful. Many studies exist that detail the extent of wastage.

One will readily concede that large format retailing with its capacity for bulk procurement and capital investment, even if it accounts for a fraction of the retail trade in the sector, might be able to make some headway in modernising the supply chain.

But before we get into the 'for and against' argument vis-a-vis FDI, we must also ponder over the fact that a modern and nationwide supply chain has been created, indigenously, for milk and milk products which account for 8.11 per cent of household expenditure.

Similarly, we have an effective supply chain for food items such as cereals, pulses, and sugar and edible oils, which together account for 24.16 per cent of household expenditure.

All other non-food goods purchased by our households such as tobacco products and alcohol, processed foods and snacks, toiletries, detergents, garments, etc, which together account for 52.57 per cent of all urban household expenditure, are made available for consumption by modern and efficient supply chains.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

Thus, what the average household does not get from a modern supply chain is a very small part of its purchase. So the argument that the pro-FDI lobby extends vis-a-vis of FDI in retail of modernising the entire supply chain is a bit exaggerated.

The supply chain as it is now is mostly modernised and efficient, and what is yet to be modernised covers only a very small part of urban household consumption.

The argument then that we need the merchants of the western world like Walmart to modernise just 9.88 per cent of the supply chain is a bit bogus and self-serving.

More than anything else it is Walmart's Chinese connection that should cause us to worry.

While Walmart has 352 stores in 130 Chinese cities with a total turnover of $7.5 billion, Walmart directly buys via its procurement centres at Shenzhen and Dalian over $290 billion worth of goods from more than 20,000 Chinese suppliers, 70 per cent of its 2010 global turnover of $420 billion. (The Atlantic, December 2011 pp82).

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

If Walmart were a country it would be the fifth largest exporter to the United States of America. This also suggests that Walmart's procurement from China is the major source of its profits.

With its huge monopsonic power, Walmart actually depresses wages, by forcing suppliers to cut costs.

A good example to demonstrate the low wages in the Chinese labour market is contained in a report by Thomas Fuller in The International Herald Tribune of August 3, 2006, which investigated the percentage split in profit in the shoe industry between the Chinese factories and those who market and sell the finished products in the US and Europe.

The factory owners after the laborious process of manufacturing makes a profit margin of 65 cents per pair of shoes, which are sold ex-factory for $15.30.

"A major US retailer, after factoring in shipping, store rent and salaries, sells the boots for $49.99. Assuming a pretax profit margin of about 7 per cent, an average among large US retailers, it earns $3.46 on the same pair of boots."

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

However the story doesn't end with the unfair profit margins. The Chinese labourers, who make the shoes, box them and even affix the price tag, are the ones who get the worst deal. The International Herald Tribune says, "Yet for all the sweat that goes into making shoes in Tianjin, the factory payroll is equivalent to $1.30 a pair, 2.6 per cent of the US retail price."

Should the salary of every worker in the Chinese shoe factory be doubled, the retail price in the US would merely go up from $49.99 to $51 or so.

By keeping wages low without the protection of trade unions, China is in effect subsidising exports. What the flow of cheap Chinese goods through the Walmart direct pipeline from China into India will do to Indian companies, particularly the SMEs can well be imagined.

Even without Walmart, Indian SMEs are being driven out in sector after sector by cheap Chinese imports. For instance, there is no light fittings industry left in India. Same for toys.

One can well imagine what a Walmart pipeline will do to the hosiery and woollen goods manufacturers in Ludhiana and Tiruppur.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

The once-prosperous clock-making industry around Rajkot has almost entirely fled to China. Millions of jobs in the semi-organised sector now stand threatened.

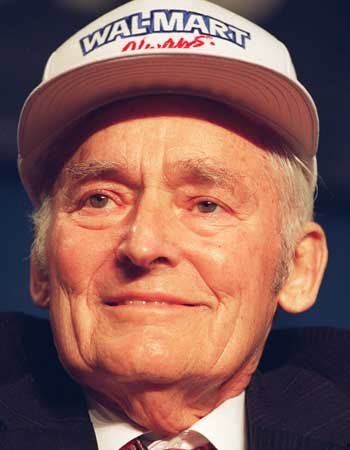

Interestingly, in 1985, Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart was forced to say: "Something must be done by all of us in the retailing and manufacturing areas to reverse this serious threat of overseas imports to our free enterprise system. Our company is firmly committed to the philosophy by buying everything possible from suppliers who manufacture their products in the United States."

Having said all this, one must concede that change is remorseless. The constant displacement of workers by machines and methods is the story of the future.

Textile mills made most weavers redundant, just as robots in automobile manufacturing have rendered many workers as surplus. This is the story in all sectors of manufacturing.

While the future cannot be avoided there is no need to hasten the pain. Big box retail will bring benefits to many stakeholders; not the least being the state, which will see improved realisation of taxes and the construction industry, which will be called to build the new retail centres.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

Better quality control and good management methods will spread into other sectors and down the supply chain manufacturers will demand from their suppliers what is demanded of them by their buyers.

Many talk of the revolution in retail, but governments must be more concerned with revolutions forming on the streets.

There are ways of achieving the former while avoiding the latter. Three simple suggestions to tweak the policy on the anvil are:

1. Insist that big box retailer's be foreign exchange neutral. That is, they export as much as they import.

2. Restrict big box retailers to outside municipal limits and to satellite towns instead of restricting them to within the 53 cities with more than a million people each. This will ease the urban chaos and encourage people to move into less expensive housing outside the big cities.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Great Walmart of China & why FDI in retail will kill Indian jobs!

3. And finally, why put limits on foreign equity holdings? Allow companies like Walmart to own 100 per cent of their business in India. At the same time the government must insist that they bring in foreign loans to finance their entire capital investments in India. This will enable Indian financial institutions and banks to remain within sectoral limits and to extend financial assistance to Indian retailers.

Above all the policy-makers must realise that while it is an American corporation earning profits for its US shareholders, Walmart is mainly a retailer of Chinese goods. Its business model is quite unique.

As Nick Robbins wrote in the context of the East India Company: "By controlling both ends of the chain, the company could buy cheap and sell dear."

In this case it means profits for the Americans, jobs for the Chinese.

The author can be reached at mohanguru@gmail.com