Photographs: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters Jyoti Mukul in New Delhi

The RBI's conservatism has been criticised by the government and industry for stalling growth. But the facts suggest a weak correlation between interest rates and economic revival.

Earlier this month, when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) indicated that a cut in policy rates could be the last in a series of four cuts since April 2012, it set off alarm bells for industry, which has not been happy despite a 7.25 per cent repurchase (repo) rate, the lowest since May 2011.

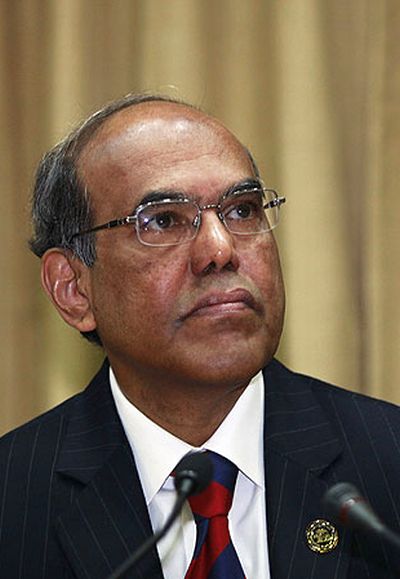

In fact, the central bank has often been criticised by the government and industry for its conservative approach in easing interest rates on grounds that high rates are responsible for stalled investments and, therefore, growth. Is this criticism warranted?

Things turned sour late last year when Finance Minister P Chidambaram openly remarked: "If the government has to walk alone to face the challenge of growth, well, we will walk alone."

The statement came after RBI Governor Duvvuri Subbarao, in his policy review on October 30, 2012, cut the cash reserve ratio from 4.5 per cent to 4.25 per cent but resisted pressure to cut the repo rate, which is the rate at which banks access funds from the central bank.

Just a day earlier, the finance minister had outlined a fiscal consolidation map and indicated that he expected the RBI to ease interest rates.

...

Why RBI reducing policy rates will not revive economy

Image: Finance Minister P Chidambaram.Photographs: Reuters

The RBI did give in eventually, cutting the repo rate by 25 basis points each in January and March this year.

But on April 2, Chidambaram made another case for a further cut when he talked of green shoots in the economy and, therefore, room for lowering interest rates.

"The government is always pro-growth and the government will always argue for lower interest rates," the minister said in an interview from Tokyo.

The central bank obliged by cutting key policy rates again on May 3, the third time since this January.

Alongside, in its annual policy statement, the central bank said, "The policy action undertaken in this review carries forward the measures put in place since January 2012 towards supporting growth in the face of gradual moderation of headline inflation." The growth argument had worked on the RBI too.

...

Why RBI reducing policy rates will not revive economy

Image: Labourers work inside an iron factory.Photographs: Mukesh Gupta/Reuters

Now, if the high interest rate regime were the real cause of concern, especially for the core sector, then the rate cuts would have obviously seen some impact on both the core sector and the index of industrial production (IIP).

But the figures tell a different story. The repo rate was down 50 basis points in 2012-13. During the same period, the IIP showed a mere 1 per cent growth, almost a third of its performance in 2011-12 when the repo rate was well above 8 per cent and was, in fact, raised to 8.5 per cent in October 2011.

Indeed, the IIP was at a 20-year low last year. It reminded some of the 1991-92 crisis year when industrial output expanded just 0.6 per cent.

The sub-indices of all the three components - mining, electricity and manufacturing - showed signs of slowing down, with mining recording a fall of 2.5 per cent. In the infrastructure sector alone, growth touched a decade low.

The index of eight core industries, which has a combined weight of 26.7 per cent in the IIP, grew 2.6 per cent during 2012-13.

...

Why RBI reducing policy rates will not revive economy

Photographs: Reuters

Since none of these key segments of industrial activity reflect any transmission of lower interest rates, it is clear that something more than the cost of money is slowing growth.

The worst of the lot, mining, has two well-known reasons for the sad story. One, illegalities giving rise to controversies, along with stalled clearances, have hit iron ore and coal mining hard.

The other reason is falling natural gas production from Reliance Industries Ltd's KG-D6 block, which brought down total domestic gas output by 14.5 per cent to 40,676 million cubic metres.

Electricity, by contrast, grew 4 per cent during 2012-13. Though it is effectively half of 8 per cent growth in the previous year, power generation showed the healthiest growth, belying analysis and industry claims that the shortages in coal and gas have hit power generation in the country.

But does that mean easing interest rates has any correlation with the power sector? The facts suggested otherwise. The sector is the one that hit sectoral caps when it came to accessing bank funds.

...

Why RBI reducing policy rates will not revive economy

Image: An employee stands inside the Tata Nano plant at Sanand.Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

Stalled power generation capacity created a build-up of bad loans in this sector and, understandably, lenders are tightening their fists.

The next major component of the IIP is manufacturing, which grew just 1.2 per cent against three per cent in 2011-12.

Here, it can be reasonably said that high interest rates on automobile loans and consumer durables are one major reason for making purchases unattractive for consumers. But were loans the only reason impacting automobile production?

Equally, high inflation also played a role. Whether it was the high input cost for imported coal-based power plants, when coal prices went up globally, or higher steel price that impacted automobile companies, to a large extent it was the pricing of the end product too that slowed demand.

It could be argued that easing interest rates may have been beneficial in that they did not let growth slip even further. But even the RBI, in its annual policy statement, underlined the message it had been sending out frequently over the past year.

...

Why RBI reducing policy rates will not revive economy

Photographs: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

In its view, the recent monetary policy action alone cannot revive growth. "It needs to be supplemented by efforts towards easing the supply bottlenecks, improving governance and stepping up public investment, alongside continuing commitment to fiscal consolidation," the central bank said.

What now remains to be seen is whether, with inflation well within what has famously come to be known as the RBI's tolerance level, growth will perk up. And, if it does, will infrastructure sectors, in general, and mining, in particular, improve their performance?

The good news is many of the sectoral bottlenecks seem to be tapering off, with iron ore mining partly resuming and the Cabinet Committee on Investment granting faster clearances for stalled projects.

So, the growth momentum could well come from sorting out the real issues and not just monetary policy.

article